This is part of a series where Silverscreen recommends films, documentaries, shorts, songs or scenes from seminal films that make for a compelling watch.

Through Samskara, a movie retelling of UR Ananthamoorthy’s novel of the same name, a group of talented artists (director B Pattabhirama Reddy, cinematographer Tom Cowan, Girish Karnad, art director SG Vasudev) come together to rebel against the caste system. Headlined by actor Girish Karnad (who has also penned the dialogues for the film), the movie takes place in Durvasapura – named after the sage Durvasa, who, according to mythology, had trouble controlling his temper. Like him, the townspeople are a rigid and religious lot. They wield caste beliefs and superstition like weapons, using them to strike down dissent. To them, the outside world is something to be feared. Modernity is opposed at every instance, and the people live their lives in seclusion, content that their staunch adherence to archaic rituals makes them pure.

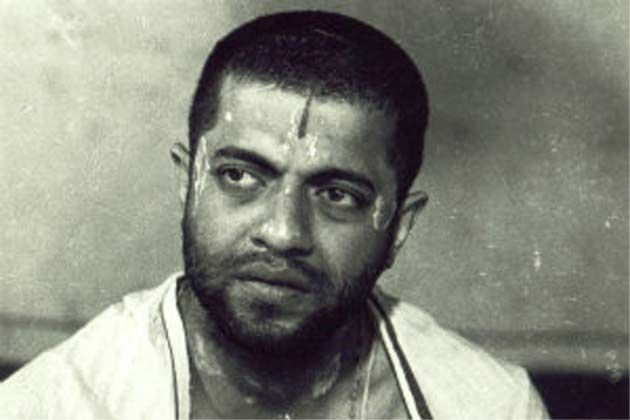

The sole catalyst for change here is Narayanappa (the late P Lankesh, in a fiery role), a man who encounters modernity and embraces it wholeheartedly. He shaves off his top knot, grows out his hair, takes up with a ‘Non-Brahmin’ woman (the incandescent Chandri, played by Snehalatha Reddy) and entices the young ones in the village to follow this new life. Narayanappa, during his life, proves to be the town’s undoing, and even more so in death. Soon after his passing, Durvasapura’s residents gather together to discuss his cremation. Nobody wants to send him on his final journey. “Touching such an impure soul will soil us all. Only a Brahmin shall cremate another Brahmin. But, Narayanappa could well be a lower caste man for all his deeds,” an old man says. Even as a corpse, Narayanappa is a nuisance to the townspeople. They cannot eat or step outside the village till he is cremated. And as days go by, without a decision in sight, the townspeople grow hungrier and restless.

Perhaps the one thing that does dislodge their deeply-held beliefs is the promise of gold. Chandri, unable to bear the way her partner’s body has been left to rot, offers the Brahmin men all her gold. She hopes that this would be enough to ensure Narayanappa’s cremation. But, Durvasapura’s residents don’t hold themselves to the same ideals that they judge others with. Greed, lust and desire war for control in every one of them. Religion here is not a matter of the spirit. Everybody wants to be the purest Brahmin, and they seek to be one by incentivising belief. As a consequence, the religion they practice seems shallow and without any meaning, leaving them vulnerable to the insistent push of modernity.

For any society to adapt, despite external threats, there needs to be a sense of community. A spirited attachment to religion would provide this. Scientific advancements and economic developments could better their chances. In Durvasapura however, there is no kinship. Only one-upmanship. In its strict adherence to a system that ensures gross inequality, it decays. Even the town’s moral authority – Praneshacharya (played by Girish Karnad) – reflects its self-indulgent spirit. His education in Kasi makes him the town’s most eligible bachelor and an authority on Hinduism. Within the setting of patriarchy, his decision to marry an invalid and then subsequently remain so devoted to her can be considered appreciable, however, even this decision is motivated by Pranesh’s greed for a direct path to God. By marrying an invalid, dedicating himself to her, and experiencing the eventual abstinence such a life brings, he thinks he will find salvation.

This incentivising becomes the town’s undoing. Each one of them do good, in the hopes of getting something for their deeds. Where then, is the spirit of the Brahmin? It certainly does not reside in Pranesh, who finally falls prey to his suppressed desires. It is not in the other townspeople, as well. Here, Narayanappa becomes the catalyst for change. He uses extremism to oppose Brahminical beliefs. He drinks, consumes beef and threatens to make the others in the town eat it too. He asks Chandri to grab a bottle of ‘holy water’ [liquor] for Praneshacharya, when the latter visits his dwelling. “It will soothe your soul,” Narayanappa says enticingly. And then goes on to blame Pranesh for sullying the mind of a local youth, Sripathy, through the ‘divine eroticism’ in his poetry. Narayanappa’s decision to stray from the life accorded to him at birth, and to revolutionise it, are commendable. Nonetheless, they’re made problematic by the way he goes about it. His is a hard-line stance that is difficult to digest. Praneshacharya occupies the same space. While he is presented as the ‘good’ to Narayanappa’s ‘evil,’ this representation is not without its problems. His sin is a certain selfishness and pride in being a true Brahmin.

When Narayanappa utters, “sin and goodness of heart are inseparable,” you wonder if this is true of both Narayanappa and Praneshacharya. The men come from two contrasting ideologies, and yet this, and their passion for Chandri does make them inseparable. They both exercise free will. Narayanappa through his ‘heretic’ acts. And, Praneshacharya through his religion.

However, one cannot ignore that Samskara, despite its revolutionary content, is all about the men. The female characters in the film, in keeping with the times, have little agency. They’re not invited to social discussions (that could very well impact their future as well), and are treated as chattel. The women are prisoners of the social system. Even those of high birth face isolation. Societal interaction is enjoyed only by the men. Only Chandri, by virtue of being a pivotal character in the movie, is shown to have spirit. In an iconic scene, she is tired of waiting on the men to decide about cremating her partner. As the debate rages over Narayanappa’s status as a Brahmin, and as the town quibbles over inconsequential things, Chandri takes things into her own hands. Her spirit is wild and free. She loves and lives as she pleases. And perhaps, this is the very thing that gives her the objectivity to view the situation as it is. Narayanappa is no more. His spirit is long gone. What lies behind is just rotting carcass. And it needs to be removed quickly. She makes sure that the body is burnt, and goes off to find a new life.

Meanwhile, mysterious deaths crop up in Durvasapura. Rats are found dead. Men and women experience raging fever, and quickly collapse. The Brahmins, in an ironic turn of events, view this as their punishment from the Gods. In truth, Narayanappa contracted the bubonic plague from a nearby town, and his rotting body had let it loose. Much before all this, however, Praneshacharya, who had spent a very long time suppressing his desires, reveals his true self when he chances upon Chandri in the forest. After a night of passion, Pranesh lies asleep in Chandri’s lap. But daylight has come, and with it, Pranesh’s wits have returned. He wanders, aimless and dazed. His wife’s death from the plague severs him from his path to salvation.

The town’s most learned individual has strayed from the path of the Brahmin. And with Narayanappa’s death, the town’s sole voice of criticism seems to have been extinguished, when in reality, it has turned inward. In Praneshacharya’s mind, his new experiences and the questions Narayanappa leaves behind, war for control over his long established puritanical notions. Even after his death and subsequent cremation, Narayanappa does not leave him alone. His brief relationship with Chandri has energised him, but it has also prompted a mystical self-inquiry. Unshackled from years of regulated belief, Pranesh exercises free will. And finds himself wanting.

Having successfully demolished the Brahmin ideology, UR Ananthamurthy and director B Pattabirama Reddy find it impossible to give Praneshacharya something new to focus on. Pranesh spends much of his life in serious enquiry, study and practice of religious rituals. Shorn of these, he is aimless. Without something to conform to, Pranesh finds life unbearable. The answer, then, seems to be a return to Durvasapura. The Brahmin may leave, but Brahminism has never left him, a seer remarks in an earlier scene. And this, ultimately, seems to hold good for Praneshacharya as well. The plague has taken away much of the residents; it could potentially harm him too. And yet, he seeks redemption in a society that is in no condition to give him what he wants.

The director, B Puttarama Reddy and UR Ananthamurthy, leave it to the audience to imagine Praneshacharya’s fate as they see fit; Pranesh hopes to redeem himself by coming clean about his transgressions. But, there is no fitting conclusion to this drama that wants to bat for progress. There’s no alternative presented to the claustrophobic Brahmin milieu. Samskara highlights the many practical inefficiencies in Hinduism alright, and even systematically demolishes all of them. But ultimately, it shies away from presenting a solution.

*****

(The writer attended the screening of Samskara as part of National Gallery Of Modern Art, Bengaluru’s outreach programme. The gallery currently hosts a retrospective on the works of artist SG Vasudev, who worked as art director for Samskara.)

Also read:

‘Vadukkunokiyanthiram’, A Dark Comedy From The ’80s That Has The Feel Of An Indie Film

Recommended

‘Aasai Mugam’, A 1965 Film With A Plastic Surgery Plot Twist

‘Panam’, A Reformist Social Drama With M Karunanidhi’s Dialogues

The Timelessness Of Onnu Muthal Poojyam Vare

‘Before My Eyes’, Mani Kaul’s Ode To Kashmir

A Group Of Youngsters Dissect The Idea Of India In ‘I Am 20’