A train runs through the heart of Ka Kha Ga Gha Nga (ABCD, 2018), a Malayalam feature film directed by Sherry Govindan. It appears on screen thrice. The rest of the time, it is a bodyless sound, resonating a man’s broken memories of the day his wife and daughters killed themselves on a railway track, and the self-annihilating guilt that he bears like a mule.

Ka Kha Ga Gha Nga is a beguiling exploration of grief, emptiness and insanity, centered on a father and his son who exist like the residue of society in a remote North Kerala village. In the film’s universe, time runs at an obscure pace. The narrative randomly slips in and out of reality, leaving the audience to their own devices to make sense of what they see on screen.

Shery’s debut feature film Adimadhyantham (2011) had won a Special Mention at 59th National Film Awards and was selected to the competition section of International Film Festival Of Kerala. Ka Kha Ga Gha Nga, shot on a shoestring budget using minimal equipment, couldn’t find much luck in the film festival circuit or at the awards, but, by far, is one of the most fascinating works in cinema to come out of Kerala in recent years. In a filmmaking space teeming with plot-driven narratives, stereotypical images and creations interested in offering answers than raising questions, Shery’s film stands out for its refusal to tie the loose ends together and offer the audience a moral compass. Notwithstanding occasional temptations to give into self-indulgences, this is a formally strong film that follows two unusual characters that exist outside the mainstream, who don’t look at life as an accomplishment or death as a frightening halt.

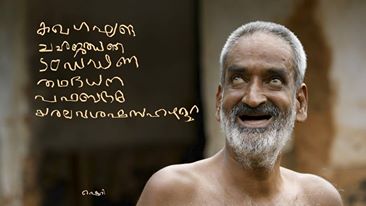

The father is a karikaalan (Kokaad Narayanan) – one of the last practitioners of an ancient custom called Kalanoottu. He is a resident grim reaper who gets invited to funerals to help the soul travel to the other side. Post every ceremony, he dies a brief death, only to wake up hours later and walk to the village’s brewery to fill the void within himself with bottles of arrack. He is dead and alive all at once; is closer to death and the dead than to life and the living. Into his old and dilapidated house comes his son Maithreyan (Manoj Kana), a street magician, after many years’ self-imposed exile. The father and the son live in two realities – their individual accounts of a common past are far removed from each other. But like parallel railway tracks headed to the same destination, they begin to live under one roof again.

Shery wants the audience to use the characters’ state of mind as a prism through which the film is viewed. In a later scene, Karikaalan, squatted on the floor with his bosom friend, laments, “I can no more tell between what is real and what is fantasy, who is dead and who is left, what is light and what is dark!” The audience go through a similar experience. We hear the sound of the train when it passes through the magician’s derailed mind. We watch the house lit by colours and sense time moving in circles when the father and the son smoke a joint in the evening. At one point, a cat metamorphosises into a rabbit. The deserted house compound becomes a bustling venue of a magic show.

There are subtle connections established between the characters. The father and the son, although emotionally distant, are tied together by their inability to lead a normal life. In the shot that follows the scene where the father places a handful of rice on his courtyard and beckons the crows – a symbol of the dead – what we see is the son’s homecoming as a hollow man.

Recommended

Ka Kha Ga Gha Nga is also an eulogy for a native artiste. Karikaalan dresses up for funerals like he is a performer on stage. He paints his face, wears head-gear, and disguises himself as the divine to heal people’s grief. But, he has no place in a modern society founded on the rejection of the beliefs and ideas he represents. The film makes a moving case for him. Nevertheless, one can’t help wonder why Sherry isn’t interested in placing the film in a specific time period or geographical location. There is no reference to the larger world outside the village either. This move, counter-intuitively, obfuscates the characters a little more than warranted.

The film’s final act, which borders on a nightmare, is a well-conceived meditative sequence on human existence, elevated by the actors’ performances. Maithreyan, who couldn’t dictate terms in his life, walks into death a happy man. We don’t get to know if he is able to pull off his final act, The Butterfly Reincarnation. This part of the film is poetic; it brims with a strange sense of hope and humanism.

****