Through Pariyerum Perumal, first-time filmmaker Mari Selvaraj attempts to take Tamil cinema to his roots. His hometown – Puliyankulam village in Thoothukudi district – figures prominently in the film, as do its people and the traditions and prejudices Mari had encountered while growing up there. His writings have traversed the same path, too

One could say that Mari’s life by itself would make for a great Tamil film; for even before his birth, he was looked at as a proponent of doom by his extended family. The fifth son brings nothing but trouble, many warned Papa, his mother. But she’d fought against all such portentous voices and given birth to him. That was his first victory, Mari tells me in our hour-long conversation. “That I exist now, because my mother – who also believes in evil spirits and doom – fought against her own opinion and that of others to bring me to this Earth. She is something else.”

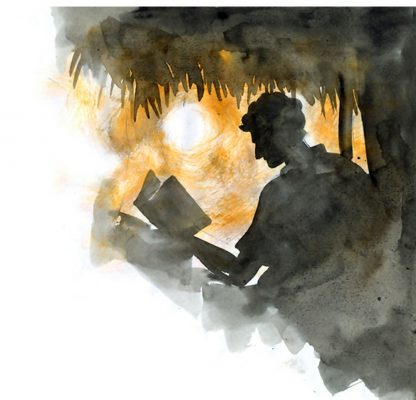

Now, 34 years later, Mari is an author and a filmmaker; the first look and teaser of Pariyerum Perumal – black against a burning orange canvas – produced by Ranjith’s Neelam Productions, created quite a stir when it released. The eponymous titular character essayed in the film by Kathir, was borne out of Mari’s many trysts with fate. The spaces that the film inhabits, the locales, are a silent hat tip to the many Pariyerum Perumals who reside in the area. “My village had several Perumals,” recalls Mari, “It still does. The Pariyerum Perumal I wrote is a man who does not cower in the face of violence. He rides into battle, fully aware of the consequences.” That describes the folk of Puliyankulam as well where his tale is based; where years of tragedies, famines, deaths and state-sponsored violence have bound families together. They have never complained, says Mari. Their resilience in the face of unmitigated disasters is what that fascinates him. Even he is made of this stock.

Mari’s past, and by extension, his thoughts, are familiar to the circle of friends he found as an assistant director. To his family though, he remains a mystery. “I became very withdrawn when I turned 15. I kept to myself. I had secrets. Like any other adolescent boy, I began to crave independence. Much of the life I lived after age 20 is a mystery to my parents. And if I could, I would keep it that way. But unfortunately for them, my experiences, however painful, are fodder for my writing.”

Mari’s ‘Marakkave Ninaikkiren’ [I Wish To Forget], a series in the Tamil magazine Ananda Vikatan that ran for a few months in 2013, wove tales of prejudice and discrimination; there were also those that showcased the frailties of human life. In one, Mari talks of a neighbour back in his town. There is sombre, sometimes colourful description of his travails, threaded with the idiosyncrasies of the village folks who get him married. Except, Sigappu Muthiah is dead when he marries, and the bride is a dressed-up banana stalk. The soul of an unmarried man is bound to wander, the villagers reason – and so, he’s made to tie a thaali on a banana stalk before being cremated.

In other entries, Mari lays bare his soul. He writes of a childhood friend with an inordinate fear of Deepavali pattasu, and his attempt at curing her of this. It literally blows up in his friend’s face, eventually leading young Mari to offer to marry her. A young woman, Jyothi Mahalakshmi, also finds frequent mention. Mari writes that he was in love with her, but their relationship never finds completion. They plan to elope. Alas, it is not to be.

He reserves his most vibrant prose for himself, though. A precocious child, Mari writes that he was often the bane of his siblings’ childhood. He would rifle through their diary entries, despite the threat of a sound beating. “My brothers began to reserve the first page of their diaries for a stern warning. My eldest brother would write all sorts of threats. My second eldest brother would write, ‘Saathane, don’t go to the next page. If you do so, your head will explode into a thousand different pieces.’ ” But the joy of peeking into others’ lives ended when Mari was unwittingly caught in a suicide investigation.

‘Marakkave Ninaikkiren’, while compelling, follows a set narrative. Mari begins by introducing a theme, the major players, and finally, ends with a revelation that is too startling for him to overcome. The series is heavy on guilt, with Mari being complicit in many of the incidents he writes; in some, he has residual guilt about his inability to help, and hence, the title – Marakkave Ninaikkiren. He wants to forget, and yet, he cannot.

*****

In the first decade of his life, Mari revelled in the warm embrace of his family; he remembers religion holding sway over them then. His mother Papa’s unquestioning adherence to traditions and culture was the adhesive that held the family together. And in this, they found kinship. “When I grew older, I began questioning a lot of the nameless things we did and followed. My parents’ lives were tied to our Gods. And in a way, ours were as well. But it was not the same for all of us. My siblings looked for solace in a different God. I did not, but that does not mean that I find the need to tell them that they should not.”

Back then, Mari also found his best self while play-acting for his fellow villagers. They told him that cinema would find him when it was time. But by the time teenage hormones surged through Mari, his childhood interest in acting had disappeared. In the place of the lively child, life left behind a sullen teenager who slammed his door shut more often than not, worrying the family who didn’t quite know what to do with him. Mari says that this phase of his life, when he withdrew from everybody and even himself, completely obliterated his old self. His heart was barren. It was up to him to create a new landscape.

And so, like it happens more often than not, he began to lead a double life. The school-going teenager existed to please his family and society. “Our right to education was a hard fought one. To turn our backs on it, knowing that several others before us fought for what we have now, would be tantamount to killing them all. I attended school religiously. But, my priority was to experience and experiment with life as much as I could, without laying waste to my schooling.”

There were impromptu trips to fairs, picnics in deserted spots, and long, lonely walks contemplating the mysteries of life. Politics found a way into Mari’s world as well, in small ways. “I never kept an eye out for discrimination when I was young. Children tend to overlook these things in favour of unrestrained playtime. But as a teenager, I began to see, hear and feel the difference between them and us. Sub-consciously I began to feel like I was irrelevant. My little heart couldn’t withstand it.”

Mari suppressed these experiences and it would take him years to recoup all that he threw away; even then, he would do so only at someone else’s urging. ‘Thamirabharaniyil Kollapadathavargal’, his debut novel, details some of these unpleasant, yet all too real experiences that helped Mari encounter world as it really was. “I did not think that I would live long enough to create something. I have put myself through a lot of pain. I have crawled through broken glass to reach this point. I have to admit, at one point I never thought this would be possible. Sure, I did dream of a life that would enrich me. But I never dared to reach out for it. Mostly because I had allowed life’s myriad experiences to pummel me into the ground.”

In many ways, ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavargal’ (published in 2013 by Vamsi Pathippagam) is a prelude to ‘Marakkave Ninaikkiren’. Both works feature similar themes. In the former, Mari lends his voice to the people from Maanjolai Tea Estate who dove into the Thamirabharani river – while on their way to the Collectorate to demand better wages – in a bid to escape police brutality. Many perished in the waters that day, and the novel’s title refers to the families left behind – the ones who were not killed in the Thamirabharani river.

But these novels would not have been possible had Mari been left to live life as he saw fit. Writing was a passion for young Mari, but there was always a reluctance to put pen to paper. If it were not for director Ram, who Mari assisted for over a decade, he says that he would probably not have written anything. “I was cinema illiterate when I met director sir. I had knowledge but not the kind that would equip me to be a creator. He forcefully sat me down and made me read many books. And then when he felt I was ready, he pushed me to write. As you will very well know, writing under duress is the worst hell one can be confined to. But that hell is where I found myself. That is where I began to create. Eventually, it became easier for me.”

Writing gave Mari a new circle of friends and family. They enriched his life and in return, made him want to be a better person. It anchored him and drove away the demons from his past. In a post on his blog titled ‘Uppu’, Mari explains that he can write only when his head swells up so much that it feels like it might burst. This was in 2014, shortly after ‘Thamirabharaniyil Kollapadathavargal’ hit the stores. His followers urged him to write more but Mari could not find it in him to do that. “I want to read for now,” he had replied to one, “My brain has been an indifferent friend. During times of betrayal, extreme hunger and a thousand love failures, it did not explode. Why would it explode now?”

And it had not. Mari’s brain continued to torment him for three more years, as he navigated the many struggles that came with life as an assistant director who had stayed on the second rung of the ladder far too long. But it finally threatened to explode when Ram sat him down and once again, urged him to confront his reluctance towards moving forward. Mari says that he then wrote the script like he had written it a thousand times before in his head. Words flew from his pen. The ghosts of the many Pariyerum Perumals from Mari’s past and the voices of those living now, urged him on. When he was done, he felt cleansed. “I didn’t realise that the people I saw and the events that unfolded around me in Thoothukudi would have resided in me for so long. It was only after I finished writing my movie that I understood. Some life experiences never leave us, even if we were too young when we first encountered them.”

Somewhere in between writing the movie and actually directing it, Mari took a break to concentrate on his greatest achievement yet. He married his long-time love, Divya whom he’d met while working for Ram; she patiently stood by him till he made a name for himself. “I didn’t want to enter into a marriage with Divya without doing something first. She was so very understanding. I would say that she is my rock.” Divya, an English teacher, seems to have provided inspiration for a scene in the movie. In the teaser for the film, Anandhi, who plays Jyothi Mahalakshmi, calls herself an angel – because, to Pariyerum Perumal, any woman who teaches him English is an angel. “That way, Divya is my angel,” Mari laughs.

He also gave the titular character many of his life experiences and goals in an attempt to root him to his surroundings. “And so, here we are. Pariyerum Perumal is me. Yet, it is also not me. I was once my mother’s son. Unquestioning. Obedient. Later, I cleaved that part of me. Make no mistake, I am still my mother’s son. But I am also the Mari Selvaraj who was forged in the fires and the pain of a thousand different brutal experiences. This dichotomy and this double life are what I want to show through my film. It is subversion, yes. But it is poetic release. It is cathartic.”

Inspiration for the film came from other quarters as well – the books Mari had written for instance. But to talk of his life experiences, and the events that Mari has described in the books, would perhaps be not too different. “I won’t deny it. A large number of people have read my ‘Marakkave Ninaikkiren’ series and my book – ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavargal’. They will know. Characters from both find their way into Pariyerum Perumal. But different names, different places.”

Recommended

Mari based the law college portions in the film and the central conflict on his own experiences. “The story is mine, but the platform on which it is mounted is new. I’m asked for the genre of the film. I don’t immediately have an answer to these questions. My guru is Ram sir. My producer is Pa Ranjith anna. Both directors have differing views to mainstream cinema. My movie has elements of the mainstream. But it will never ever espouse any thoughts and ideals that would clash with Ranjith anna or director sir. So, I can only call Pariyerum Perumal a biography. I agree it is my story. But the landscape it unfolds in is new.”

However, Mari says he has little interest in creating a film with purely commercial aspects. ‘Mass entertainment’ is a phrase that he often has trouble comprehending. “In our village, cinema was everything. It was love, hate, anger. It was politics. When cinema can be so many things, how can it simply be entertainment? How can it only be a couple of comedy tracks? The medium is so much more than that. And through the paths forged by Ranjith anna and director (Ram) sir, young filmmakers like us finally have a voice. We are showcasing our stories, real ones with honest hearts, in the hope that cinema will be what it is meant to be – love, hate, anger and politics.”

Pariyerum Perumal, starring Kathir, Anandhi, Yogi Babu, with music by Santhosh Narayanan and cinematography by Sridhar, releases this Friday. Watch the teaser here:

*****

The Mari Selvaraj interview is a Silverscreen exclusive.