Pikchar With Rita is a fortnightly column on cinema by Rita Kothari. She’s a Professor of English at Ashoka University. She does not “do” film studies.

***

Some days ago, when it seemed too purposeless to do anything for yet another time, I went into the kitchen armed with songs of Kishore Kumar. His voice infused into the chores a lyricism that I can seldom resist. One particular song stood out, ‘Tere bina jiya jaye na..’ which translates as ‘[Simply] can’t live without you…’ I had heard this song several times in Lata Mangeshkar’s voice; but it was different listening to Kishore Kumar.

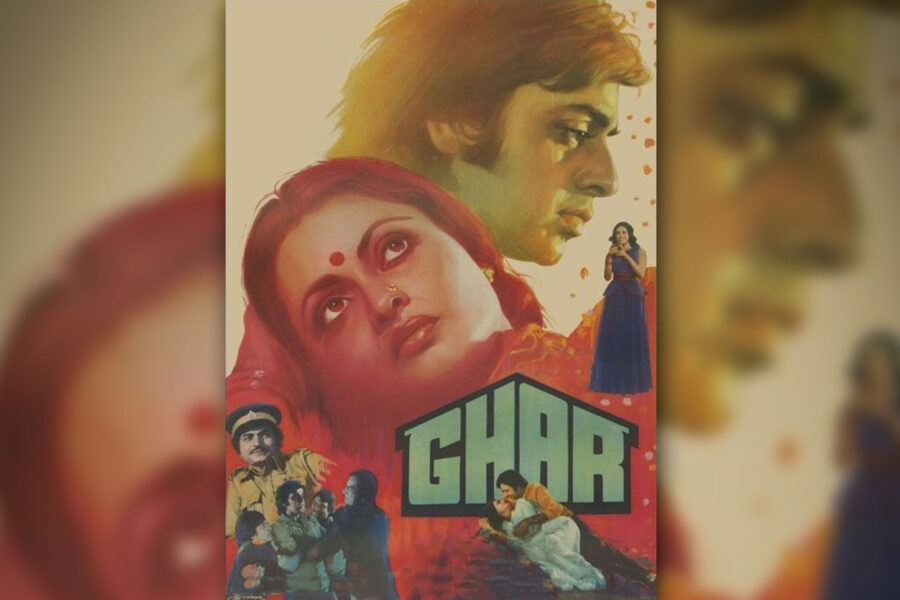

A grainy image from a distant past appeared before my eyes when as an eight-year-old I must have spotted the poster of the film Ghar, with Rekha in a saree that went around her bun and the pencil-thin eyebrows which in the subsequent years became thick and prominent, adding to the Rekha trademark beauty. The film was rated “A” when it appeared, and so clearly did not form a part of childhood staple. The notes of this song buzzed in my head through the day and the film drew me to itself. It may not generally be advisable to watch films of all the songs we like, the visual effect can be quite staggering and ruin the songs for us for the rest of our lives. But with this one, I was willing to take chances, with the added testimony provided by the duo RD Burman and Gulzar, who collaborated in good films and created immortal songs. Also, in one of her most disarming and straightforward interviews Rekha mentioned how she was always surprised to receive the praise she had, for she had not thought of herself as a great actor. Ghar, she mentioned, was exceptional.

The Lata Mangeshkar version of ‘Tere Bina Jiya jaaye na…’ plays in the film as Arti (played by Rekha) visits every nook and corner of home picking up lingering traces of passion-filled nights. Evocatively the song says, ‘Jab Bhi Khayaalon Mein Tuu Aaye/Mere Badan Se Kushbuu Aaye/Mehake Badan Mein Raha Na Jaaye’, which translates as ‘Whenever you enter the thoughts, my body gives out a fragrance, and the fragrant body is hard to live with.’ This is intense desire in a married couple that finds hard to have a dwelling in which love-making could find its full expression. The sensuality of the soft nights has been witnessed by the walls of the modest and rented home that they have finally managed to find. This ghar, or home, and this song with an aching longing, stay in the film as a background score against which little things happen.

The legitimacy of love-making (even) in a married couple is sometimes suspect in India; watched now by the police, now the joint family and neighbours. But the notes of haunting songs take the spectator through these surveilling hurdles with a promise of an intimacy that seethes quietly. However, when an enormous tragedy strikes their life and Arti is raped by four drunken men on the street, the texture of home and desire and relationship changes.

Ghar is one of the early films about rape, and one that focuses upon the afterlife both of fulfillment and ruptures in marriage. This may also explain why the film has gone unnoticed for it was doing the harder job in Hindi cinema; the job of dwelling slowly, of lingering, of an unhurried pace and unresolved ends. When the relationship is corroded, gestures second-guessed the notes grow faint, for Ghar manages to show the sheer difficulty of being normal with a traumatised self and body.

Recommended

The Kishore Kumar version I heard plays at the end of the film, the last sequence, when Arti is found at the railway station and has not taken a train to leave Vikas, while he has not stayed home and let her go, instead run helter-skelter to bring her back. The song ‘Tere bina jiya jaye na…’ plays again, but evokes an ache to belong and own, and the voice of desire is now a voice of brokenness. This version is played against the clamour of a railway platform, for it is not about the longing of the body, but of the soul and this longing has survived the brokenness. It evokes far more solitude in the street than the one experienced at home, in the ghar. As we come to the end of this rumination, it is to remember the not-remembered films that slipped through cracks and take chances on tracing the song to the film. May melody unlock you.