Director: Céline Sciamma

Cast: Noémie Merlant, Adèle Haenel

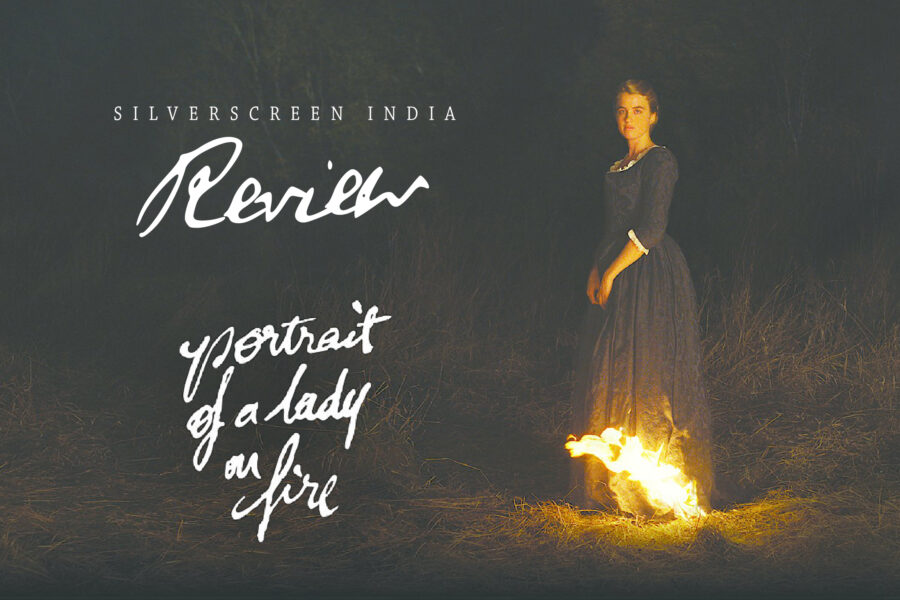

“Is that me? Is that how you see me?,” Héloïse (a luminous Adèle Haenel) quizzes Marianne (Noémie Merlant) the moment she sets her eyes on the titular portrait in Céline Sciamma’s lesbian romance, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (now streaming on Amazon Prime).

To be fair, there’s nothing quite wrong with the painting– it’s an adequate work of replication, if slightly mechanical. But while Marianne interprets the stillness of her subject as adherence to the “rules and conventions” that influence the definition of great art, Héloïse sees the lack of life as an affront.

More importantly, the dissimilitude of the resulting portrait – an outcome of a one-sided artistic endeavour – reveals to her the disinterest that Marianne displayed in truly seeing her, favouring instead for her to be seen. “I find it sad that it isn’t close to you,” Héloïse sharply tells her before storming off. It is in this discord between the art and the artist lies Portrait of a Lady on Fire’s ambitious ask: At what point does art turn a female subject into a mere object?

merlin_165236466_3ca7d30a-a35c-476c-85a4-94c053587644-superJumbo

Set in 18th century France, the gorgeous, sensual period epic unfolds in the remote shores of Brittany, its central romance playing out through a flashback. Marianne is a Parisian artist who has been summoned to paint a portrait of Héloïse, a former convent girl and the younger daughter of an Aristocratic family.

Her countess mother intends to send the painting to a Milenese nobleman – if he is pleased by what he sees, they will be wedded. But there is a catch: Héloïse has no desire to get married, having registered her protest by refusing to pose for a painter who left without even getting to see her face. For Marianne, the task at hand is to then paint Héloïse on the sly without making it evident that she is looking or even observing. To Héloïse, she should appear as nothing more than a walking companion.

For most of the film’s first half, as the tension and attraction between Marianne and Héloïse simmers and threatens to rage, Sciamma employs this subterfuge as a device to underline the chief power imbalance between the observer and the observed. By keeping Héloïse in the dark about painting her, Marianne effectively also shuts her out of the process of creation – a literal embodiment of the countless mute women who have ended up being immortalised in various paintings by male artists over the decades.

What we know about these “muses” is entirely dependent on the information that the artists replicating them choose to tell us, which is to say, not much. Like in marriage, even in art, the fate of women, Sciamma argues, lies in someone else’s hands and more crucially, at the mercy of someone else’s gaze.

That Portrait of a Lady on Fire is as much concerned with uncovering the story as it is with pinpointing who it is that gets to tell that story, is revealed in tiny bursts of detail that somehow seem to contain a lifetime of information. The myth of Ovid’s “Orpheus and Eurydice” for instance, informs the tragic turn of the electric albeit forbidden romance that develops between Marianne and Héloïse.

In one scene, the three women – who include Sophie, the house help – gather around and read the fateful passage about Orpheous looking backward at his lover Eurydice despite being told not to and thus dooming her to remain in the underworld. It has long been assumed that Orpheous had looked back out of his own will, unable to control himself – an act that Marianne interprets as him making the poet’s choice, “He chooses the memory of her.”

Which is also to say, that it is him who has the power to decide whether Eurydice gets to live or die. But Héloïse raises a curious question: What if Eurydice was the one who told Orpheous to turn back? The implication being: Could she have not been the victim and commanded her own fate?

There’s another striking subplot about Sophie’s unwanted pregnancy, perhaps the film’s most brazen display of radical feminism, that is elevated from being a mere footnote and recreated into a moving record of abortion legtimised in art.

Sciamma gets playfully literate about the neglect in the scene: When Marianne flinches and looks away while Sophie’s abortionist inserts a poultice to perform the procedure, Héloïse insists that she look right back, a comment, if not a confrontation of the historical evidence of society turning a blind eye to women’s experiences.

Recommended

In the film, once Héloïse is made aware of the deception, she looks back as well. She agrees to pose for Marianne’s second attempt at painting her but not as a lifeless object. “If you look at me, who do I look at?” she asks Marianne midway through their sitting, a line that echoes the film’s themes of both love and art being a product of collaboration. So even when their romance meets its end, the memory of it lingers forever – in the way Marianne looks at Héloïse, in Héloïse’s eyes (the film’s final sequence is as good a proclamation of love as it can get), and in the essence of their feelings that they preserve in their art.

For a film that deploys the subversion of gaze (Sciamma has called it “a manifesto about the female gaze”) to propel action, A Portrait of A Lady on Fire is built predominantly on the erotic pleasures of looking instead of just being looked at.

The camera complies with close-ups as stolen glances become a shorthand for the extent of passion, longing stares – illuminated by candlelight or set against the never-ending blue skies – reveal desires instead of hiding them. And as Marianne lets Héloïse hold her hand while painting her, it’s as if both women infuse life in each other.

There’s no better evidence of it than in the film’s most breathtaking scene that arrives early on. Marianne and Héloïse are seated side by side on the beach. The camera is beside Marianne as she steals glances at Héloïse, who returns the favour. They keep taking turns to stare at the other until, at last they look at each other in a mutual stare, one that reverberates with feeling, intimacy, and more importantly equality. After all, loving is an art in itself.

The Portrait Of A Lady On Fire review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreen.in and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.