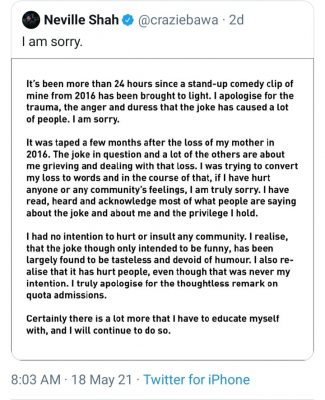

Neville Shah, the standup comic, received widespread condemnation on social media, after his video clip from 2016 for his joke about the reservation system resurfaced on social media on May 16.

In the joke, Shah was seen calling a doctor treating his mother, ‘quota doctor’ in a derogatory manner. He implied that the doctor- someone who receives their education through the caste-based reservation system in Indian institutions- was bad at their job.

Shah’s insulting remarks about caste have triggered a discussion on the lack of diversity in stand-up comedy in India. Members of online community say that jokes like the one by Neville Shah punch down on people from marginalized communities. They have spoken about how stand up comedy is limited to upper caste circles because the tone and themes of jokes are elitist.

Members of the community add that access to stand up comedy is usually limited to upper caste circles due to high cost of renting venues and ticket pricing.

Since the initial clip by Neville Shah, Twitter and Instagram have had discussions and discourses, calling out comedians including Abhish Mathew, Sorabh Pant, Atul Khatri, Neeti Palta, and Rahul Subramanian, for making casteist, misogynist and distasteful jokes.

While few comedians have come out in support of their peers on social media, others have chosen to remain silent.

“Stand-up comedians should always ask uncomfortable questions to people who have power and privilege. What Neville Shah said was not punching down but sheer ignorance that you are unaware how deep-rooted caste is in our society. The fault is also of that audience which laughed,” said Sanjay Rajoura, a comedian who is part of Aisi Taisi Democracy, a Hindi political satire show interspersed with music, speaking to Silverscreen India.

Unjust spaces

Agreeing with Rajoura, Gurumurthy Rathnam, who held a Twitter spaces conversation with around 600 participants on May 17, said that the inherent casteism in stand-up comedy is not just a North Indian phenomenon.

“In yesterday’s spaces, winner of the show Queen of comedy Nivedita Prakashan recounted the times when comedians opened their set with the lines ‘Hey, I’m a Tambrahm’(Tamil Brahmin). People also had come up to her and actually asked her if she is one or not. It means there is something inherently wrong with the scene,” said Guru.

“Neville Shah is not just one person, there are a lot of Neville Shahs over here,” he adds.

According to him, such introductions reinstate caste pride of a community which has enjoyed privilege in the past. It also alienates many others from communities who want to be part of the stand up comedy scene when they realise that the caste composition of the stand up comedy circle is homogeneous, he said.

Manaal Patil a comedian from Mumbai, whose video titled ‘This is how you crack quota joke’ went viral after Neville Shah was called out, said that he was denied stage time in comedy clubs because of his caste.

This is how you crack quota joke @craziebawa pic.twitter.com/yzam4TRMHz

— manaal patil (@manaalpatil) May 19, 2021

“They used to refuse me (stage time) telling me that I am doing the same old jokes (referring to jokes on the caste system). When an upper caste person is telling me not to talk about caste, what is it, if not casteism?” asked Patil.

Patil said that jokes on the reservation jokes are not inherently bad in nature. They need to be funny and punch up towards the privileged, he said.

In defense

However, Patil also comes in defense of Neville Shah and others who have cracked casteist jokes in the past. He says that they are not inherently vile.

Patil says that Shah stepped in to help him when an audience member bullied Patil during an open mic night.

“The video that I tweeted on reservation was just a joke directed at the situation. It was not because I took offence to Neville Shah’s video. As a comedian, I feel like everybody should be allowed to joke about whatever they want to joke about,” said Patil.

Others like Patil have also supported this stance.

Stand up comedian Azeem Banatwalla, part of the group East India Comedy tweeted, “If you find an experienced comic making a joke today that is outright racist, casteist, anything else, by all means, let them feel your wrath. But reacting to jokes from five or ten years ago as if they were made today in my humble opinion, is counterproductive.”

Everyone gets a few things wrong in their job. Nobody's an amazing writer/coder/photographer/manager from day one. Like all jobs, we have a bad day. Or put out shit work on a deadline. But we learn along the way. For comics, our lessons tend to be rather more public than others.

— Azeem Banatwalla (@TheBanat) May 19, 2021

Like Banatwalla, Dhruv Rathee, an Indian Youtuber, too felt that the criticism is unnecessary. “It is stupid to define a person with what they said seven or eight years ago when they’re doing the exact opposite now. Many people have said and done things as teenagers which they later regret. People evolve with time, it is normal. This cancel(ed) culture is crazy and self-destructive. Support you!” Rathee commented on Instagram.

Calling out

According to Sanjay Rajoura, time helps people evolve. The opinion they held 10 years ago is not the same as the ones they hold now, he says.

However, tweets and posts on social media do not have an expiration date, he says. With more access to online spaces, it is only right to expect those from marginalised communities to hold celebrities and stand up comedians for offensive tweets on religion, caste and gender, he says.

“What is even more problematic is the fact that people think that ‘call out culture’ is damaging. But here’s the deal, we do not ‘destroy lives’. We only want to raise that first call. Here, people (stand up comedians) inherently have power,” says Namithaa, an intersectional queer feminist activist from Chennai.

Sharing a similar opinion, Mathur Sathya J, who regularly watches stand up shows, says that despite calling out, things barely change. “Here is an ignorant Brahmin comedian, who is giving opinions about the caste system. Just because these people acknowledge their privilege, we have to stand up and give our standing ovation and listen to what they say about caste,” he says.

Rajoura says that apologies issued by stand up comedians are so not clearly indicate any sort of reflection by those who have been called out. It is not the responsibility of the person who has pulled out a tweet from years ago to reflect.

I am truly sorry. pic.twitter.com/s1xE90Qp3J

— Abish Mathew (@abishmathew) May 20, 2021

Over the last week, writer Hannah Stephen has been tearing through apologies issued by comics on Instagram and has been actively educating people about what one must say when being called out for being casteist and misogynist.

“In all the apologies, the primary problem is that they (comedians) do not see the need to explain how they plan to do better. They treat the apology like a band aid that covers the issue. It looks like a PR (public relations) issue that needs to be contained,” says Hannah.

Hannah gives the example of comedian Abish Matthew, who in 2012 tweeted a sexually inappropriate joke on the former Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh Mayawati. She says that he does not address the casteist nature of his tweets. “They were not just misogynist. They were also casteist. To not address it, when the issue was brought up in the first place by the DBA (Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi) community, is an insult to the very people who were further disadvantaged by such remarks,” she says.

She says that apologies must reflect on how ones actions have fed into the system, perpetuating oppression. One must also name the system of oppression, she says.

Hannah says that those who are part of this systemic oppression must not call actions as ‘thoughtless’ and ‘unintentional’. If so, one must explain why. “They were part of your consciousness, so you didn’t consider it to be oppressive,” she says.

She instead suggests that people say ‘I’m sorry for not being more intentional with my choice of words’.

Recommended

“Say, ‘I’m sorry for not being thoughtful and reflective of my biases’. Say ‘My thoughtlessness is actually casteism and it is inacceptable’,” she adds.

Rajoura says that it is responsibility of those who have posted online to reflect and evaluate about whether or not their body of work has improved and been more accommodative with time. He adds that people who have called out should not be expected to be educated by the community they have oppressed in the past.

“If they (those called out) have grown, then it should show it in their work and not just in their words,” said Rajoura.