I was born in 1985 in Nagpur. The place I grew up in for almost 25 years of my life was a Dalit basti called Takli Sim, made up only of erstwhile Mahars (now Buddhists). The general notion that growing up in a Dalit basti means that one has to have some brutal experiences of caste-discrimination wasn’t true in our basti. Of course, its location in the context of the city suggests that it is an untouchable colony on the banks of Ambazari lake, outside the boundary of the mainland. To the left of our basti was another basti of Kunbis (we called it Kunbipura) and behind our basti, on the hill, was a huge settlement of Kunbi-Marathas, Jaitala, which outdid our basti in terms of area and numbers. My father often used to say, “We have defeated these boys from Kunbipura many a time in wrestling”. This militancy and rage was evident in cricket matches between boys from our basti and Kunbipura or Jaitala. It was in this set up that I was first introduced to motion pictures in the mid-90s. It was during Ganpati festivals when Kunbis screened movies on a big white-canvas in the open ground. They sat on one side of the screen, and we Dalits on the other; the screen thus metaphorically became a partition between Kunbis and Dalits. The most unforgettable movie I watched on this screen was Amar Akbar Anthony.

My father had bought a TV (AT&T with antenna) as early as 1988, for my third birthday. There was another reason for his buying the TV. In 1987, Ramayana, written and directed by Ramanand Sagar, (which has been resurrected now during Covid lockdown) was first broadcast on Doordarshan (DD). In 1988, Mahabharat, directed by Ravi Chopra aired as well.

I heard that on Sundays, when these serials were being broadcast, our basti would come to a standstill to watch these shows in my home. Hundreds of eyes of Dalits then indulged in watching brahmanical narratives. (Interestingly, in 1987, the Maharashtra government published Riddles in Hinduism by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. In Riddles in Hinduism Ambedkar provided a critique of Hinduism.)

My father was also obsessed with Bollywood since his adolescent days. I vividly remember all those Sundays of calm afternoons during the mid-90s when we would go on his bicycle across the city to watch matinee shows in theaters in Nagpur. I was about ten years old then. Panchsheel, Alankar, Liberty, Smruti, Sudama, Bharat are all theatres in Nagpur I’ve been to with my father. These theaters are a part of some of the fondest memories I have with him. Bollywood is an inseparable part of these memories.

My father had been a driver (he recently stopped working), driving the long goods-carrier for a livelihood for almost forty-five years; 16 to 18 hours a day of work with a meagre salary. He spent 45 years among the proletariat: drivers, cleaners, coolies, and mechanics.

***

The 1970s was a period filled with unease and rage among the youth of Mumbai and Nagpur. Well-read youth from Mumbai founded Dalit Panthers in 1972 as a means of addressing this rage. Prominent among them were Raja Dhale, Namdeo Dhasal, JV Pawar and Arun Kamble; all voracious readers, furious poets, visionaries of non-brahminical aesthetics and soon-to-be writers who were going to change the literary imagination of India. They were angry young men in real life.

During this period, Mumbai was going through a transition in politics. Shiv Sena, with its ambiguous agenda of Marathi Manus became active. Clashes between Shiv Sena and Dalit Panthers were not so uncommon in this period. The dynastic rule of Congress party witnessed popularity as well as unexpected decline during the same decade. All these events culminated in fostering one element among Dalits and the other oppressed castes: their anger against their exploitation in the social, and political domain of Indian life.

In such a situation, the demand for a national hero became not only a necessity but it had grown into a promising commodity in the cultural domain as well.

The Angry Young Man phenomena, manufactured by Bollywood — making Amitabh Bachchan an ‘Industrial Hero’ as M Madhava Prasad called it — made this commodity available for the nation but only at the cost of erasing the history behind the anger. One that was against the caste-system.

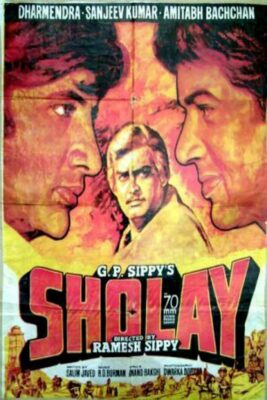

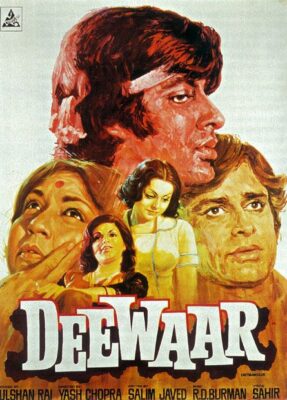

Bollywood mobilised the anger of the masses and gave them an Angry Young Man, who manifested their anger on-screen while fighting against enemies: state and feudalism but never against caste. On-screen, this Angry Young Man possessed the anger of Dalit-Bahujan masses but was playing the role of savarna characters, seldom being an identity-less proletariat. Zanjeer (1973), Deewar (1974), and Sholay (1975) are crucial in popularising Amitabh Bachchan’s Angry Young Man.

***

81KOa6ucxoL._SL1500_

My father often says that he watched Sholay in the theaters of Nagpur, three back-to-back shows in a day, innumerable times in 1975. My grandmother says that my father stopped going to school when he was in the 8th standard, as his obsession to watch these angry-young-man movies grew. He had seen all of Bachchan’s movies in this period, lingering around theaters in Nagpur, as if trying to find some solace from a life full of struggle; looking for answers in a reel world. As soon as he stopped school, he had to work for a large family of nine people, though his passion for movies remained unabated.

Bollywood’s biggest victims became the proletariat class among Dalits who were engaged in labour, and could not afford the company of books.

***

Dalits Panthers had come into existence in 1972 in Mumbai. Within a year, they attracted the attention of the society as well as the media, both Marathi and English. Their inspiration was The Black Panther Party founded in the USA. Dalit Panthers got on the nerves of everyone: savarna writers, politicians, and society. Skirmishes between them and Shiv Sena became regular in Mumbai. Later, these real developments formed the background for reel depiction of stories. Dalit/Ambedkarite/Buddhist population, and some other castes too in a minuscule number, were influenced by the literary imagination of Dalit Panthers. But there were some like my father, very much under the influence of Bollywood.

29e4e77b5ad2000224c0156a181e9f3b

In 1973, a year after Dalit Panthers had been formed, Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer released. It was the first movie that made Amitabh a hero, an angry young man, in the nation’s imagination. Amitabh played the role of police inspector Vijay Khanna, Khatri by caste. He portrayed the character of an honest police officer, a state representative sympathetic to the stories of Dalit-Bahujans. Next year in 1974, Yash Chopra’s Deewar released. In this, Amitabh played the role of a coolie (Vijay Verma) at a dockyard who rose to prominence as a criminal gangster known for his ethical/moral way of functioning. It was an epic drama, with many subtexts.

Notably, during this time, the Dalit-Buddhist community had secured government jobs and achieved a bit of economic prosperity, and became a class unto itself. However, only a few among the Dalit community resembled Ravi (inspector and state representative). The majority of them still resembled Vijay (a victim of the past). Vijay’s anger, thus, is very much anger borrowed from Dalits.

The third movie in this sequence was Sholay (1975), the biggest blockbuster; the movie is a part of the memory of generations and resides in their mind as a symbol of a particular political time. In this movie, Amitabh played Jai (an identity-less petty criminal with some morality), alongside Veeru (played by Dharmendra). For Thakur’s revenge (also the representative of state, law and feudal order in the movie) played by Sanjeev Kumar, Jai had to die. In all these three films, the state remains alive.

The impact of these three movies was so colossal and irreversible that “the Amitabh Bachchan phenomenon can be said to represent the arrival of populism on the national arena,” as M Madhava Prasad wrote in his book Ideology of the Hindi Film.

***

Interrogating this curious phenomenon of Amitabh’s Savarna characters becoming angry young men on screen, Kuffir Nalgundwar in his article at Roundtable India throws a very pertinent question our way: “So what was the savarna angry young man angry about, anyway? There wasn’t much to complain about in the 70s, from his perspective. There weren’t any broad, significant challenges to brahminical hegemony, in the economic or social spheres. Savarna hold on the polity allowed no major intrusions, Mandal wasn’t even constituted until the late seventies, and nobody even looked back at its report until the late 80s”.

Recommended

The effects of these Bollywood visuals were so irrevocable that its viewers/consumers, people like my father, remained under its influence for decades; from this their idea of the world had taken another turn in which they possessed anger but had forgotten the means by which this anger could liberate them.

The Dalit Panthers, however, the real angry men, guided people to pursue liberation in real life and their work was shaped by the acknowledgment of the roots of oppression: the caste system. Their anger was present in their work. As was their social history. Unlike Bollywood.

Yogesh Maitreya (wanjariyogesh85@gmail.com) is a poet and translator. He is a PhD scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, studying the history of Ambedkari Shahiri in Maharashtra. He is also a founder of Panther’s Paw Publication