Pikchar With Rita is a fortnightly column on cinema by Rita Kothari. She’s a Professor of English at Ashoka University. She does not “do” film studies.

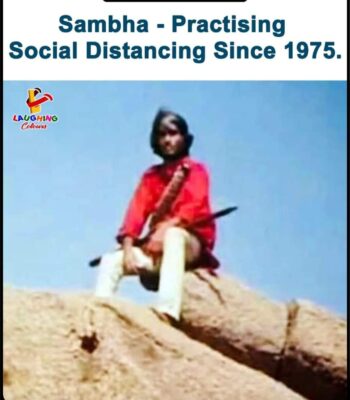

When Gabbar Singh in Sholay paced up and down menacingly, he had Sambha at least three feet away, if not more, answering questions like, “Arre O Sambha, kitna inaam rakhe hai sarkar ham par?” (How much reward for me has the government declared?) And Sambha would reply, “Sarkar, poore pachaas hazaar.” (A full fifty thousand.) A meme about “Sambha practicing social distancing since 1975” brought back memories of Sholay. Rather it tickled the lived memory that only gets eclipsed from time to time, never to be fully gone.

08ef748f-ccc1-415d-93ed-5fad91074bdc

Our relation with certain films undergoes a renewal every few years. Now it’s possible that this meme or the associations and hilarity it evoked may not mean anything to generations that have not watched Sholay. Believe me, there are some such who haven’t even heard of Sholay. It’s also possible that there are Sholay equivalents in Tamil and Telugu cinema, which clearly I haven’t watched. So we can all forgive each other for such ignorance.

A taut action and melodrama packed film like Sholay is not unique now since it first appeared. And in other traditions of the world, a run-of-the-mill genre. Perhaps without the heartbreaking death of Jai, or the sizzling dance in RD Burman directed songs like Mehbooba. If you were to break Sholay down in pieces, it may not stand the test of its permanent place in our memory. But what endures in memory is seldom about the thing itself. It is about what that thing did to us, as a community of spectators, binding us through associations of fear, humour, excitement.

We re-enacted the dialogues of Sholay in my family, where one of us would say one dialogue from the film and another would respond with perfect faithfulness to the script. The repetition was made possible by the fact that each of us had watched Sholay ten times or more. It was also reinforced through a social transmission of Sholay dialogues from one person to another; not unlike verses from scriptures that circulated amongst Brahmins through oral recitations.

In that sense, Sholay is not about Sholay alone, but the specters it produced for many of us. We tend to think for instance that spectators aspire to become like heroes they watch, but Sholay made its villain aspirational. One of my family members laughed like Gabbar Singh, initially as a demonstration of his own talent to imitate, but gradually that laughter was his natural laughter. The ringing and demonic laughter reverberating through rocks when Gabbar Singh’s team of three people escape death, only temporarily, is etched on the minds of audiences. The hilarious self-delusion of Basanti who talks non-stop but also says, “Mujhe befazool baat karne ki to aadat hai nahin,” (I am hardly interested in unnecessary conversation) has come in handy to describe a garrulous person. You would not know, for instance, how useful it is to remember, “Mujhe to sab police waalon ki suratein ek jaisi lagti hai” (I find all cops look-alikes of each other) dialogue from Sholay has such universality.

In days of lockdown thinking of the future is terrifying; but for a brief moment thinking of Sholay from the past (nay, present) reminds me that there are ways of being a community at distance – from both time and space.