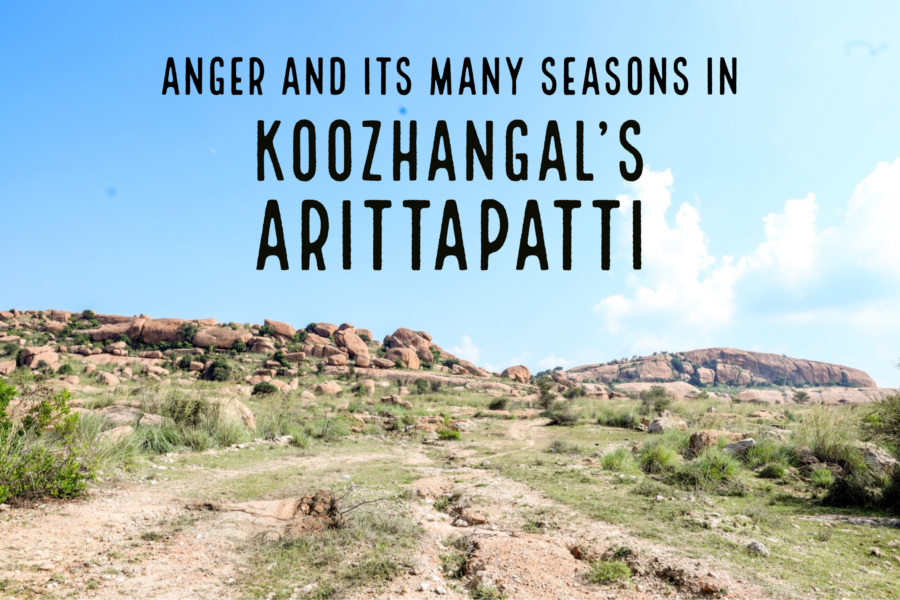

It is a pleasant day in December when we decide to travel to Arittapatti, a cluster of seven hillocks near Melur in Madurai district, to ask the village’s residents if they know anything about Koozhangal or Pebbles, the film which was nominated to be India’s entry to the Oscars in 2021.

The route to the villages surrounding the hills are pleasantly green. There is water in every ditch, dugout, stream and tank. Herds of cattle stray away from the prickly shrubs that dot the Arittapatti landscape. Their herders too aren’t wearing turbans to cover their head as the day is not too hot. “It has been pretty pleasant here. This is probably the best time to visit our village. Look at our lush paddy and banana fields,” says V. Jaya, one of the first residents we encounter.

This contrasts the searing heat of April and May that the director of Koozhangal P. S. Vinothraj, paints in his frames. The film, which has had a successful run in the film festival circuit, shows this exact same location during summertime when temperatures rise up to 40 degree celsius on average. The stark difference in the visuals almost effortlessly explains the lives of the people living there- one which answers why everyone seems so angry in the film.

In the film produced by Nayanthara and Vignesh Shivan, the channel carrying water to a series of villages in and around the hills is completely barren. The ground is broken and caked up. The fields are without any crops in cultivation. There is not a drop of water in the landscape- only brown hills and occasional glimpses of dry grass. Ganapathy, the protagonist, (played by Karuthadaiyan) comes across this same bone-dry channel collecting dust and crosses it with ease as there is no water. His body showcases skin laden with beads of sweat. His anger too matches the terribly fateful day when he must bring his wife Shanti and their daughter Lakshmi back home after driving her out- a result of a drunken quarrel. He verbally abuses and beats his young son Velu- his companion on this journey- intermittently to find ways to deflect his anger. The season nor his persona favour him.

The arduous journey makes him travel to the nearby village- Idayapatti- where his wife is originally from. He takes his young son Velu along to be his tool of communication. What follows is their nearly silent story and a walk of about 13 kms in Madurai district’s peak summer.

Director Vinothraj says that the landscape is central to these loud moods. “On the hottest days, do we also not become Ganapathy?” he asks as he recounts times when he and the members of his crew sat in different parts of the hills at different points of shoot because they just could not manage their anger. “The wind that reaches the mountains reflects a veppa kaathu (hot air). There is not an inkling of respite. During the shoot, we did not wear our slippers as the protagonist did not wear them in the film. It would otherwise interfere with live sound. We could not afford any such luxuries to avoid discrepancies during the time of editing. We had to live the lives that the characters lived and so in some ways, we also embodied Ganapathy’s anger,” he says.

This anger and the arid Arittapatti hills remain common in almost every frame of Koozhangal. Over two and a half years since its filming, it feels like the residents and its director too continue carrying small portions of this difficult emotion through their day. They all choose to take breaks and receive respite when they can.

First brush

Vinothraj’s first encounter with the hills of Arittapatti came at a very young age. “I often tell people that it is easy for those in Madurai to become saamiyars or godmen,” he says.

At the slightest sign of inconvenience or altercation, male members of his family would often take off to the Jain caves in Arittapatti and claim that they would want to be one with God. Most of them would live in Melur, a taluk in Madurai district which is a short hike to Arittapatti in order to create a scene. The men would find cozy spots in these hills used nearly 2,500 years ago by Jain monks, and wait for others in the family to beg them to return.

“If my father or any other member of the family went in search of this temporary ‘salvation’, young kids like me will be taken along to soothe their anger. For me, these trips would often be like excursions. There would be small holes in the rocks which would collect rainwater. I would play there, observe all the ants, snakes and other creepy crawlies,” he says.

Vinothraj says that he came back to the same location in 2017 even though he frequented his village Melavalavu for events or functions in the family through the years. He was clear from the very beginning that he wanted Arittapatti to be the area that he showcases in the film. This, in more ways than one, is linked to anger too.

A few of years before Vinothraj wrote this script, he received a call from his family about his sister being forced to return to her family home by her husband after a bitter altercation. The director said that it was humiliating for his sister to return to her husband’s house after this big fight and it damaged the self-esteem of the rest of the family. “The real incident happened very close to the hills. I knew that I could not physically make my brother-in-law take that walk. I wanted to see him bring my sister back to his house. I wanted him to ask my sister to come back. The only way I could do it was through a film,” he says.

It seemed like fitting punishment at various points to see Ganapathy walking tirelessly, he adds. Velu’s anger and innocent taunts at his father Ganapathy are clear depictions of this contempt. At various points in the film, Velu can be seen outwardly fighting his father. He tears rupee notes that his father gives him. He runs for his life, making Ganapathy miss the bus back to their village after visiting Idayapatti, thus creating the need for the long walk back home. He acts as though he does not have any matchsticks, refusing to give Ganapathy light to smoke his beedi. He even shines a mirror on Ganapathy’s bareback on a hot summer day, causing a sharp sense of irritation for the latter.

Vinothraj says that the story pretty much began as a revenge plot. “There is a scene in the movie where Ganapathy catches up to Velu and beats him for having made him run. He folds his own shirt and wears it like a thalappa. It is like he is trapping all his anger in his head. It takes a long time – fear even – for him to take the thalappa down,” the director says.

Fury on sets

To capture this plain anger, Vinothraj says that they did not use any camera fillers. “The sky has to be cloudless and must not cover the sun in order to ensure that we get consistent shots throughout their schedule,” he says.

The days leading up to the filming of one particularly stunning 12-minute sequence of heightened drama between Ganapathy and his wife Santhi’s family were stressful according to the director.

For four days, the entire cast and crew rehearsed their dialogues, positions and walks in order to ensure a perfect single take shot, getting the entire emotion and sound through live capture. Vinothraj’s crew had to request members of the village where they were shooting to ensure that no television sets would be turned on that day. “When we went for the take, everything wonderfully fell in place. The dialogues, the emotion, the cameras were all just perfect. This was until the guys from the sound team told us that they had barely registered any of the sounds. This got us pretty down and agitated a lot of us. We went for two more such takes on the subsequent days,” he says.

When Vinothraj first came for research to Arittapatti in 2017, he was asked to shoot a trailer for his then financier who did not understand the film in detail. Vinoth gave him just 27 pages of a script in contrast to regular feature films that have a minimum of 120 pages. “I was pretty tense and nervous about communicating all this to the producer through a short trailer and I was in Arittapatti hoping to get the perfect shots. On the way, I was deeply annoyed since my bike ran out of petrol. I was cursing and walking to the nearest petrol bunk when I saw a long snake making its way across the road. I realised that the only way to put a break on anger was by adding such elements of fear. We made use of this in the film too,” he says.

Vinoth also interestingly points out that they auditioned a total of 65 people in order to find Chellapandi. He says that he required someone who could understand the role that the young boy plays in entirety.

“I wanted someone with a similar family background so that it would not come across as odd while filming. Chellapandi is very affectionate towards his family, particularly his brother. This is similar to the dynamic that Velu shares with his sister in the film. He also understands alcoholism and its effects. This is exactly what the script demands of this young person- someone who understands the way adults behave around them,” he says.

A child’s lens

Children often have a way of turning moments of drama and intensity into those filled with joy, the director says. Stories surrounding Velu and an unnamed child whose family scouts for rats in order to eat their meat, are testaments of this, he adds. There is truth in a child’s perspective though it has several elements of imagination, he says.

The director, who grew up in poverty, spent much of his childhood working in a flower shop in Madurai city. His only exposure to films would be to listen in on shows from three different movie theatres in his area as he did not have enough money to regularly watch the films. He went on to work in a textile mill in Tirupur in order to earn a living for his family. “Even at our poorest, I never stopped seeking joy or finding moments of pleasure in the dullness of everyday life. I also never registered that I was poor,” he says.

Vinoth says that there were days when his father would wobble drunkenly through the street leading to his house and begin verbally abusing his mother, sisters and him. “In order to protect us, our mother would ask us to rush out. My sisters and I would literally play hide and seek with him so as to avoid being beaten up,” he says.

There is also truth in his portrayal of women. A New Yorker review says that ‘in the movie’s final scene, Vinothraj’s vision of women’s relentless subsistence labour and men’s rage comes full circle’. “Vinothraj films the women’s work in intimate detail and at awestruck length, showing exactly what a mere cupful demands of them,” the critic says and calls it one of the most memorable endings in recent cinema.

Although the children can be seen being oblivious to their poverty in the film and finding joy in tough moments, the same cannot be said for the women in the film who labour tirelessly on the sidelines.

Anger and its payoffs

Contrary to the intense sentiments of anger displayed in the film, Vinothraj seems like someone who loves to laugh. Throughout our two-hour conversation in Chennai, the director breaks into several cackles easily. He recounts stories about people he once loved while making black tea and laughs while talking about members of his family. He talks about a multitude of different emotions including feeling sheer joy and contentment.

Since the screening of the film at various international festivals and winning awards, Vinoth says that the lives of many people who have worked on Koozhangal have gotten better. He says that both Karuthadaiyan and Chellapandi are leading more financially secure lives. “I am too,” he says, smiling.

Kind fans and well-wishers have gotten him gifts like an iPhone and watches- things he says that he never thought he would buy for himself. His most precious gift, he says though, is a tote bag that an old lady bought him when he attended the film festival in Transylvania, Romania. “For months on end, I could never understand what made people connect with the film. Why did they like it? Why did I win the Tiger Award (for best film at the 50th International Film Festival Rotterdam). I could not attend any of the events due to COVID so I did not get my answer. When the opportunity to go to Romania presented itself, I made my way instantly. I was very nervous before the screening but immediately after the runtime, I was bombarded with questions,” he said.

Koozhangal had two encores at the festival. An old Romanian woman who did not speak Vinothraj’s language, broke down and told him about leading a life very similar to that of Shanti’s.“She insisted that she buy me something so we stopped at a souvenir shop and bought a jolna pai (a tote). Enga ponalum oru kezhaivi vandhuruva enna thedi. (An old woman will somehow always find a way to contact me).” he says.

His family too is excited about the fame and recognition he has been getting over the last year. Some of his family members have even acted in the film. “Every time I win an award, they put up stories and write long status messages on Facebook and WhatsApp,” he says. The support has been overwhelming, he says.

What he is dumbfounded by is that he has not once been asked by his brother-in-law about whether the story was based on him. “I see it as a big sign of maturity,” he says.

Vinothraj is already working on his next project which will also be centred around the Madurai landscape, he says. For now, he is happy to collect awards of his films and wrap them in green bubble wrap to place in an obscure corner of his living room.

Arittapatti today

To this day, residents of Arittapatti village say that the hills remain a favourite for angry men. “Some genuinely come there to pray, others just loiter about. Some drink and waste their time in the hills while the rest walk around to herd their cattle or forage for some wood,” says C. Murugeswari, a resident who has been running a microfinance company for women in the area for decades now.

In December, anger usually dissipates though, she says. The men have to work in the fields or drink so there is little time for display of emotions.

Arittapatti in December requires journalists, tourists and residents alike to wade through a small lake in order to quickly get to see the sites of historical importance including the Jain caves there that date back to 2,500 years and a rock-cut Shiva temple from the 8th century.

The men who perform the pujas at the temple are kind and timid. S. Dharmaraj, the main priest of the temple, whose family has been taking care of the temple upkeep for four generations now says with tears that he is deeply devoted to the temple and that he hopes for the future generation to also be theistic.

Dharmaraj says that he regularly advises people who come to the temple to offer and gently throw palm sugar and puffed rice around the hills of Arittapatti. Anger is prohibited unless the spirit of the gods enters one of them. “The treats are mostly to feed the wildlife and the birds that live here. It is not compulsory,” he says. Vinothraj is a proponent of this mode of paying respect to the hills too. He says that it was one of the first things he did before starting shooting, wishing for good omens.

Arittapatti in December also means that the dry bushes near the hills do not remain brown anymore. They take the colour of a gentle green. The bright blue sky is studded with clouds and a trek in the brown hills does not seem particularly daunting. It sometimes threatens to rain.

The other men from the villages surrounding the hills say that they want to remain anonymous as they are officials with government postings. They say that alcoholism and anger exist in their village just as much as it exists in the next. This is irrespective of whether it is December or not.

Vinoth who went back to Arittapatti during the monsoon soon after his shooting, says that he initially returned to Chennai, his place of work, with the same intense feelings of anger and rage that he carried from the days of shooting in the hills.

When he returned to the area during the rain, he felt like his spirits were lifted. “I refer to the hills as an entity because everytime I go there for research, I find stones, rocks and pebbles teaching me things that I can learn nowhere else. Something in me has changed. Arittapatti has given me a lot more than I can give back. It feels like the hills have a mind of their own. They have made me write the story. It feels like I am just a tool,” he says.

Recommended

Despite attributing his entire success to the hills, Arittapatti does not return the favour. It instead blesses him with complete anonymity. On a December afternoon in Arittapatti, all of our 16 interviewees say that they have no idea what Koozhangal is.

Arittapatti pcture credits: Manikandan