I’m running late for my interview with Mysskin, but the unyielding security guard at the gate insists that I fill out all columns of the visitor’s register first. As I scribble hurriedly, another man at the desk tells me that the security guard – an old man – is an actor too. He appeared in Mysskin’s Yuddham Sei. The rigid guard blushes, and offers me a shy smile.

Mysskin’s apartment is on the first floor. A note on the door reads. “No admission for assistant directors till September 2015.”

As he lets me in, I notice an unused table in one corner of the hall and a treadmill in the other. The walls look like they need a fresh coat of paint. Mysskin reclines on a huge chair, and asks his assistant to make coffee for me. When I refuse, telling him I’m recovering from a bad stomach, he stares at me for a second before offering me Jasmine flavoured green tea.

Then he drops a big carton of custard apples on the table in front of me. “To treat your bad stomach,” he smiles, asking me to help myself.

mysskin-interview-8

Mysskin returns and tells me, “I just got back from a haircut. Give me 15 minute to get ready. Meanwhile, you can try other flavours of green tea.”

*****

mysskin-interview-1

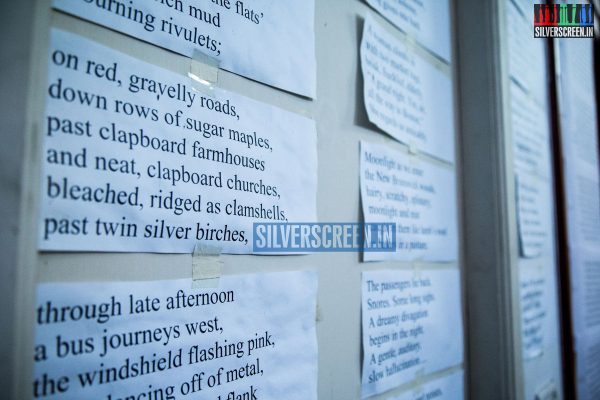

We move to his office now. There are books everywhere – around corners, on tables, behind his chair, and yes, on the long couch too. Freud and Chekov, Conrad and Thornton; everyone has a place in the room. Also, fittingly, Lopez’s Of Wolves And Men. The dressers have poems pasted on them: The Moose by Elizabeth Bishop, Ode on Indolence, Ode on Melancholy, Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats. And there are three pictures on the walls. Kurosawa, Bresson, and Kitano.

“I live with books,” Mysskin says in a matter of fact tone before proceeding to clear a chair for me to sit in.

And from behind the newly clutter-free table, he starts talking.

*****

He begins at the beginning. “I was about seven then,” he recounts. “My granny used to tell me a lot of stories. From mythology to folklore, I listened to about 3500 stories from her. I fell in love with stories and the pleasure of losing myself in those magical worlds.”

“And when my granny got too busy, I stumbled upon the world of literature.”

mysskin-interview-10

His was a childhood filled with films and books. He remembers the first movie he watched: Enter The Dragon. “When coming out of the movie, my dad asked me if I liked it. I couldn’t explain to him how awestruck I was after watching Bruce Lee on the screen, so I just said ‘I loved it, dad!’ He immediately took me back to the box office and got us tickets for the next show. I watched it again.”

He was six then.

mysskin-interview-2

“Why don’t you come to me?” the wall appeared to be telling Mysskin. “It looked like a cinema screen. I had found my calling. I decided to pursue telling stories on screen.” The revelation came late, but Mysskin is philosophical about it. “When the disciple is ready, the master appears.”

*****

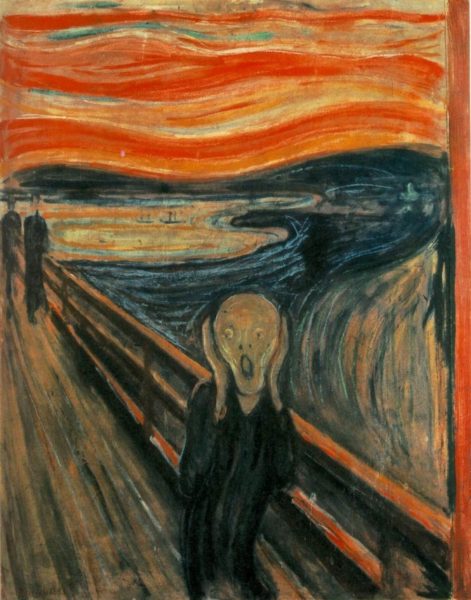

Art is Mysskin’s muse.

The Scream

Besides serving as a creative stimulant, the different kinds of music that he listens to helps him connect with his composers. A list that includes Ilaiyaraaja, his composer for Nandalala and Onaayum Aattukuttiyum. Raaja is a father figure to Mysskin – literally: he calls him “daddy.” “To work with Ilaiyaraaja, you have to be prepared. When I talk to him during our composing sessions, I tell daddy that I want music like Philip Glass or Beethoven or Mozart.”

“Philip Glass’s music has no changeover. It is flat and rhythmic,” Raaja tells him, “Let him be da. Beethoven isn’t all that great. But Mozart. Mozart is the greatest.” Mysskin is beaming when he recounts the conversations with Raaja and the maestro’s knowledge of world music.

A younger Mysskin was a fan of Dr Balamuralikrishna and SP Balasubrahmanyam and practised some lessons on his own. “The first lullaby that I listened to was Annakilli Unnai Theduthu. I fell in love with music after that.”

The violin and cello are Mysskin’s favourite musical instruments. His film’s scores are predominantly string based. “The violin is very melancholic and deep,” says Mysskin, “it creates the right mood for my movies.” He adds laughing, “The violin is one of man’s best inventions. Even better than the computer. We’ve abused the violin in Pisaasu, as Arrol is a violinist himself.”

*****

mysskin-interview-7

The Mysskin motifs.

“The close-up is the most boring shot,” observes Mysskin. “Seventy five percent of Tamil movies are filled with close-ups. Did you know there were only 12 close-ups in the three and a half hour long Seven Samurai?” he asks rhetorically.

“Close-up shots drag the narrative out. They stop time, and tire out the audience. They are an anathema to good filmmaking. My protagonists are always moving. They’re rushing. There is chaos. There is confusion. And all of that is better projected through shots of legs.”

Mysskin recently discovered a video [link at the end of this article] in which Bresson uses only the actors hands to narrate a story. “I was shocked when I saw that. It was so beautiful. I think all my life I will not be bored of showing legs of my actors.”

Monologues are very symbolic, says Mysskin. “In our real lives, we do talk a lot to ourselves. My characters talk a lot to themselves because as a filmmaker I completely understand that thousands of people are listening to them. Deeply. Meditatively. And my messages are conveyed that way.”

*****

Mysskin is embarrassed to be called an auteur. “I think it’s a tall claim. I’m saying this not out of humility, but out of clarity,” he quips.

mysskin-interview-9

*****

“Movies are not mere entertainment,” Mysskin says with some passion. “Any work of art that moves people cannot be just mere entertainment. I watched Interstellar recently. It’s got hard science. A lot of people who didn’t understand the science told me that they loved the movie. Isn’t it amazing that your daughter can become older than you? Interstellar was an absolute wonder to watch. It moved me. It challenged me. It gave me hope. It enriched me.”

And naturally, Mysskin is also not a big fan of classifying films based on centres. He treats his audience as “one whole” group with “aesthetic sensibilities.” He elaborates. “A story should not always speak to the mind. The primary target is the heart. I don’t want to divide my audience into classy and sub-standard. Think of Anjathe, Chithiram Pesuthadi, Alaipayuthey and Sethu. Everybody liked them. A good piece of art should overcome all divisions. Only through art can we shatter our boundaries.”

*****

Pisasu Movie Stills

In the last few years, Mysskin has arrived at a stage where his films’ success doesn’t affect him. “When making my first two movies, I was very childish. I was competitive without understanding the process of movie-making. Now I don’t brood over my flops anymore.”

Onaayum Aattukuttiyum, which he produced himself under his Lone Wolf Productions banner, was a commercial flop, Mysskin admits. “But after the release of Onaayum Aattukuttiyum, I earned over a lakh admirers. That is enough for me. Now I think Onaayum Aattukuttiyum was the biggest hit of my life.”

He then adds with a grin, “I strongly believe that success is an excess.”

*****

Quite like the name of his production house, Mysskin is a loner. “I am separated from my wife. Not legally though. But I know I’m separated. My friends are very worried that I am always alone. But I am married to movies. I think I am lucky enough to be doomed to live like this forever,” he laughs.

Recommended

He pauses for a minute, clears his throat and continues, “If you don’t suffer, if you don’t have pain, you can’t do anything genuine. You must notice that I am purposefully avoiding the word ‘create’. Because I am not God. If I don’t have pain, I don’t see anything intensely. I don’t see anything intimately.”

Referring to his protagonists again, Mysskin says, “That is why my movies revolve around the dark side of the human psyche. More than happiness, suffering is a gift to a writer. My protagonists suffer a lot. But in the end, they do realise that life is worth living.”

As an afterthought, he adds, “I do know that I am lonely. I feel it. But I don’t regret it.”

*****

Video Links:

Hands of Bresson:

Mysskin original photos by: Dani Charles.

Photo of The Scream: Wikipedia.