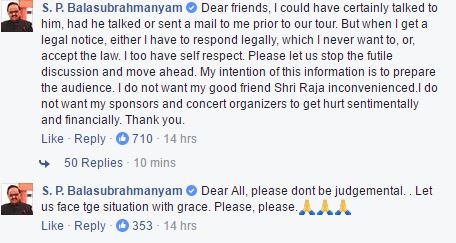

On Saturday morning, singer SP Balasubrahmanyam, who is in the US for a series of concerts to celebrate the 50th year of his singing career, wrote on his Facebook page that he had received a legal notice from lawyers representing Ilaiyaraaja to stop performing songs composed by Ilaiyaraaja without his consent. The concerts are organised by Balasubrahmanyam’s son, SPB Charan, and are for-profit.

Once the notice was received, the concert organisers had two choices: pay royalties to the composer, or stop performing them. Balasubrahmanyam, whose Facebook page has over two-and-a-half million followers, said that he would stop performing the composer’s songs going forward. “I am ignorant of these legalities,” Balasubrahmanyam wrote, “If it is a law, so be it and I obey it.”

Legally, the singer is on shaky territory. Ilaiyaraaja holds copyright over all his compositions, and public performance – especially for profit – without the copyright owner’s consent is illegal.

AR Rahman, Ilaiyaraaja’s fellow composer, also prefers to own the copyright to all of his compositions. In a 2006 interview with The Times Of India, Rahman said, “I won’t run to music companies in Mumbai for the rights for my songs every time I want to perform them at concerts. Music companies must recognise the changing ground reality. Today, conventional outlets for music sales are drying up. Soon all music will be free while the performers and performances will be paid for.”

Perhaps that is why Balasubrahmanyam decided to invoke a higher power at the end of his statement. “If this is the design of God, I obey it with reverence.”

A singer, in a concert organised by his family, tries to use songs he has no right over to make money. The copyright owner demands that he stop doing it. He stops. That should have been that. But reactions have been decidedly less black and white, with several celebrities and fans opining that the composer should have sacrificed money to for the sake of his friendship with Balasubrahmanyan.

*****

Ilaiyaraaja, popularly known as Raaja, was an aspiring music composer with big dreams and little money when he first met Balasubrahmanyam in the 1960s. He was assisting various music directors, including GK Venkatesh. Balasubrahmanyan used to sing with Ilaiyaraaja and his brothers as he continued to look for opportunities to sing in movies. He got his break before Ilaiyaraaja did, and was singing regularly in both Tamil and Telugu films by the time Ilaiyaraaja debuted as a composer with the chart-buster Annakili. It took him three films as composer before he used his friend Balu to sing for him, but after Oru Naal Onnodu Oru Naal, there was no looking back.

In the decade that followed, Raaja composed hundreds of songs each year, and the majority of his compositions were sung by SPB, KJ Yesudas and S Janaki. The old order of composer MS Viswanathan and his favourite singers TM Soundararajan and P Susheela – was gradually phased out, and this was now the Raaja era.

Courtesy: Ilayarajainfo.blogspot.com

*****

Ilaiyaraaja has composed music for over a thousand movies over the last 40 years. Even though he is in the twilight of a storied career, he is still a sought after music composer in Indian cinema, and his songs are played hundreds of times everyday on radio and television; they are downloaded often on YouTube. Yet, his income from music royalties has been meager.

In late 1970 and early 1980, cassette tapes were not as common as LP records in India, and several of Raaja’s albums were released by Colombia records. Raaja describes the haphazard system of royalties that existed then. “Colombia records used to buy the rights to most of my movies then. Their representative would show up at film poojas and pay the producer 10,000 rupees. There was no system of tracking sales or royalty income beyond this. Until the next film’s pooja, when they would pay the producer another 10,000 rupees.”

To change the system, Raaja founded a company named Echo Music with his old classmate, Subramanian. The first album released by Echo was Moondram Pirai, and the company routinely released Raaja’s albums for several years. Other audio labels – INRECO, Sangeetha – also came up in the 1980s, primarily releasing Ilaiyaraaja’s albums.

Yet, Raaja says, “I did not get any royalties from any of these companies. Even my own friend’s company that I helped him found, Echo Records, did not pay me royalties.” The licensing agreement with the audio labels ended after five years, yet they continued to make money off Ilaiyaraaja’s compositions without renewing the agreements.

Last year, Ilaiyaraaja won a judgment from the Madras High Court to prevent five music labels from continuing to sell his music. “I am being forced to seek legal recourse,” he would say in a press meet after the judgment. “I am not one to fight court battles, but I had to for the sake of creators.” Sitting next to him was Kalaipuli S Thanu, president of the Tamil Nadu Film Producer’s Council, whose members had been promised a share of royalty revenue by Ilaiyaraaja.

Last year, Ilaiyaraaja won a judgment from the Madras High Court to prevent five music labels from continuing to sell his music. “I am being forced to seek legal recourse,” he would say in a press meet after the judgment. “I am not one to fight court battles, but I had to for the sake of creators.” Sitting next to him was Kalaipuli S Thanu, president of the Tamil Nadu Film Producer’s Council, whose members had been promised a share of royalty revenue by Ilaiyaraaja.

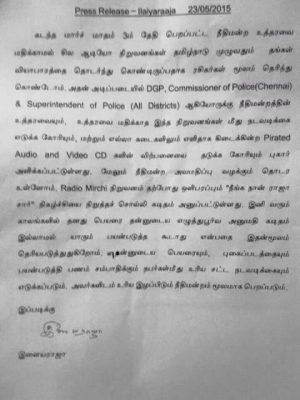

After the judgment, he filed a complaint to the police requesting them to stop sales of CDs sold by these labels, and also to stop the Radio Mirchi FM radio channel to cancel their Neenga Dhaan Raaja Sir program. “Nobody should use my name or likeness to make money without my written consent,” Raaja said in a press release then.

Surprisingly, the statement met with widespread criticism even though Raaja was just trying to assert his rights over his own work. Even though it appears so, Raaja’s works are not in the public domain for anyone to use; and if they make money from it, he is justified in asking for his share.

But to most Tamils, Raaja’s songs are part of their cultural fabric. They feel that they own the music, and have a right to listen to them.

But do they also have a right to profit from the songs?

*****

In this context, the legal notice sent to the organisers of the SP Balasubrahmanyam concert and the reactions to it should not be surprising. The composer’s estranged brother, Gangai Amaran betrayed his lack of understanding of copyright in an angry statement on television. “He has been paid for the songs. Once he is paid, the songs are public property,” he said, and sang a few lines from a popular song for no apparent reason. “Like the wind, like the rains,” he added, “his songs are public property. Let people enjoy them.”

Recommended

For a neutral observer, the legal notice did not impose any undue burden on Balasubrahmanyam and his organisers. There was no demand for past royalties – which the copyright holder has a right to demand – but just a simple ask to cease playing songs going forward without seeking consent from the composer.

The media savvy Balasubrahmanyam should have known that his statement would incite anger and disappointment. Several of his biggest hit songs are composed by Ilaiyaraaja, and the songs by the duo are among the biggest draws at any concert.

He could have asked his organisers to work out a royalty arrangement with Raaja, but he chose to issue a Facebook statement where he tried to take the high ground.

Paying a copyright holder his due for using his songs costs money, though.

Facebook posts, not much.

*****