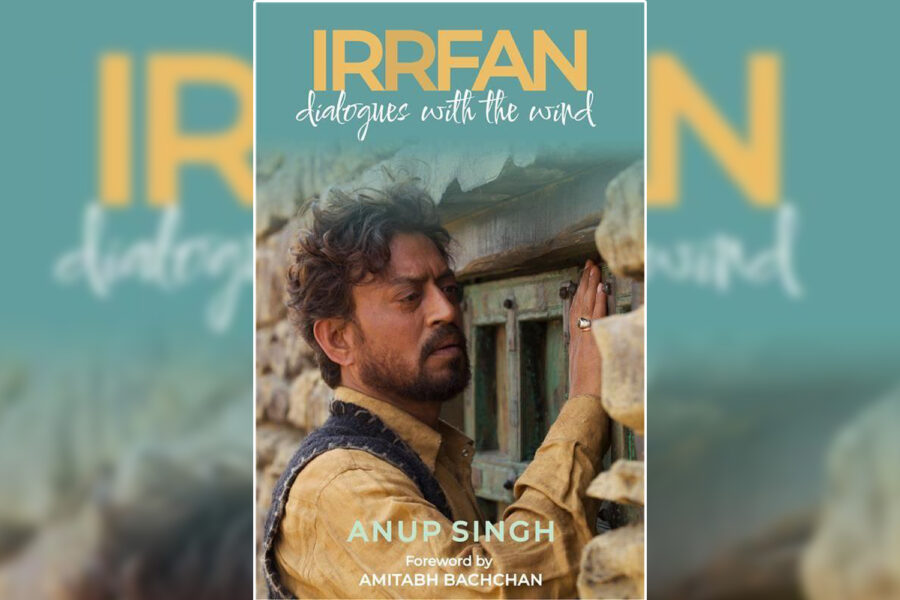

Irrfan: Dialogues with the Wind is filmmaker Anup Singh’s debut book. Singh’s association with late actor Irrfan Khan dates back to their first film together, Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost. The book is neither a mere collection of facts, nor a map that traces the trajectory of the late actor’s life. It is a treasure trove of memories and, as Singh calls it, future memories. The following are excerpts from the book.

*****

I hear the muted calls of the birds outside as I raise my head from the pillow in the dark room. My wife, Catherine, is lying beside me. Her eyes are wide open. I stare at her, my brain a blur of dream- images and foreboding.

“Your phone,” she whispers.

My mobile phone vibrates again on the chair next to the bed. And again. It keeps pulsing in my hand as I grab it and hurry out of the room.

I see the date and time as I click my phone on: April 29, 2020, 4:54 a.m. I read the first message and I cross quickly to the back-door of the house, turn the key and stumble out into the garden. Birds rise from the cherry trees and there are swallows in the air. I hear the stir of the three poplar trees in the distance. They emerge and fade in the early-morning mist.

I walk to the big cherry tree and stoop under its branches. I search and find a plump cherry and hold it in my hand. I sit down at the base of the tree and the words of the messages keep reverberating in my head.

‘Irrfan Khan dead.’ ‘Irrfan Khan passes away.’ ‘Admitted to Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital in Mumbai yesterday, Irrfan passed away this morning.’

It was on February 16, 2018, that I received this message from Irrfan: “Baat ho sakti hai? Kuch ajab hi safar ki tayyari shuru ho gayi hai. Aapko batana chah raha tha.” I called him immediately and he told me about his being diagnosed with malignant endocrine tumours in his gastrointestinal system. A cancer. He asked me to find out about doctors and hospitals in Switzerland, where I live, who might have some experience with this particular kind of cancer. His voice was a little hushed, but calm. I held on to my own emotions and tried to speak as pragmatically as possible.

I started calling various doctors in Switzerland that very day, but hardly a week later Irrfan called to tell me that they had probably found the best doctor for him in London.

It was just after a year now and he was gone. Under the cherry tree, I hear the swirl and flutter of the birds and I remember Irrfan’s words to me from a long time ago when he was introduced to a hunting falcon at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival. He was invited to the beach outside the hotel where we were staying, and then led to a large white tent set up for him. Irrfan sat down on a rug inside the open tent, his back against a cushion. The falconer carried in the bird perched on his glove-covered hand and settled it on Irrfan’s knee.

Irrfan and the falcon sat watching each other for a long time. Later, I had asked him, “What did the falcon say to you? And what did you say to the falcon?”

Irrfan wrote back to me, “The falcon, it said, ‘Even though I miss you, I don’t miss you, I’m too busy with myself.’ I asked the falcon, ‘Are you sure?’ At this he turned his head and looked at the bright, glittering sea and went silent. After a while, the sound of birds around started echoing in my head and they kept growing.”

*****

And I, sitting under the tree, bite into the cherry I’ve been holding in my hand and listen to the birds, and among them, I hope to hear Irrfan’s voice. Catherine finds me under the low-hanging branches of the tree. She sits down beside me. “I want to call Sutapa,” I say to her.

She nods. I look at the phone in my hands.

“I can’t,” I say after a while.

“Write to her,” Catherine suggests.

I wait. I want the birds to say something to me, give me a message from Irrfan. The birds keep chattering but they have nothing to share with me.

I type out a word on my phone and then another and then a few more and press ‘Send’. It is a long, desolate moment before the phone buzzes in my hand. Sutapa’s reply brings tears to my eyes. It’s a confirmation. Deep down somewhere, I had kept saying to myself that, perhaps, it was all a mistake. They got it wrong.

I cannot even bear to imagine all that would be steadily disintegrating in Sutapa’s soul. She and Irrfan had met when they were students at the National School of Drama, Delhi. They have been together for 30 years and have two sons together, Babil and Ayaan.

*****

Recommended

I spend the rest of the day wandering through the house. Every hour or so I walk up the stairs to the first floor, returning to the room we had done up for Irrfan and Sutapa’s visit. Just about a month ago, while in London again for a check-up at the hospital, Irrfan had said that they would come and stay with us for a couple of weeks.

We had chosen a fine white cotton bedspread with delicate, handstitched motifs of elephants, also in white. The curtains over the window, which opens onto the garden below and the village beyond, were also of the same material.

On this hot, summer day, I watch a ray of sunlight slip in through the window and fall in a sparkling rectangle on the bedspread and the hazel-coloured wooden floor. The lines and textures on the pale amber wall across from the window is alive with flickers of reflected light. The rest of the room lies in a lustrous shadow.

Leaning against the doorway to the room, there is a moment of respite. For a while, I imagine Irrfan at the window, still unable to stop himself from rolling a cigarette. I see him pick up a date. He nibbles at it. It takes him a long time to finish it. He holds on to the edge of the seed and studies it, turning it slowly in the sunlight, enchanted by the grainy weave of the seed’s skin and its shape. He looks towards me. Perhaps we could play a game of carom? He hunches forward over the board resting on the bed, his deep hazel irises flash in the hooded folds of his eyes. His middle finger tensed in the clasp of his thumb, ready to send the striker slithering across the powdered surface to nudge the ruby-red queen into one of the board’s pockets.

For a few moments, I live the consolation of a stream of events and exchanges that would never occur.

There are so many memories, and now, so many more imagined memories. The film flows, gets stuck, stutters, starts again. Gets stuck again, palpitates, melts and everything goes black. Then, it starts again. Irrfan, as I’ve seen him, imagined him, thought about him — Heer, Shams, Majnun, grass, not tree, earth, less fire, and becoming more and more water in the time I knew him. Neither man nor woman, a tumult of questions unencumbered by answers. A rhythm, a touch, a gaze that acknowledges and excites play. Buoyant behind masks, his diverse disguises allowed him security, entertainment and participation in social rituals. But it was clear to all who knew him that his yearning was for the ineffable, the unfathomable, the terrifying and life-galvanising unknown — not only within himself but in all that whirled around him in the universe. I see him, with the string of a kite in his hands — unruffled, vulnerable, eager for the unpredictable change.

Still the surge of memories, soothing, harrowing, continues: I enter the room and see Irrfan stretched like a tattered marionette across a large white bed, his feet hanging above the floor. This was in the same hospital where he would finally die three months later. This was the last time I saw him. When he awakes a few minutes later, he laughs so hard that he has tears rolling down his cheeks as I describe to him the character he’ll play in the new film we’re going to do together. Still later, resting back against the pillows, he looks at me and says: “I can hear it call, Anup Saab. Bulawa aa gaya hai (I’ve been summoned). Beautiful voice. It’s so tempting to let go.”

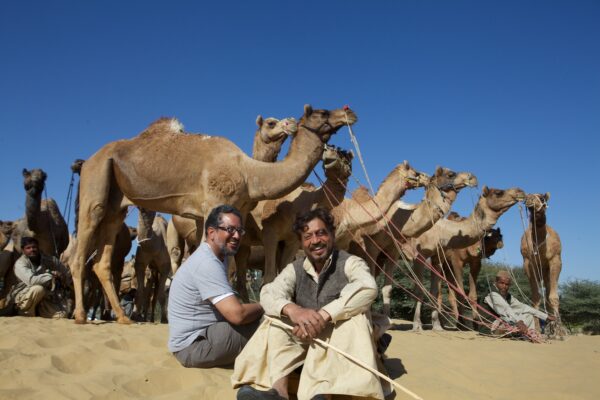

And I want this torrent of memories to stop. Yet I am relieved when they don’t. The horror in his eyes during the shoot of Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost (2014), our first film together, , when I spring a scene on him in which he has to dance. During the shoot of The Song of Scorpions (2017), our second film together, he holds up a scorpion by its tail and caresses its head. At the film’s premiere at Locarno, hesitant, but, finally, with a cigarette in his mouth, he joins me and Golshifteh Farahani, the Iranian actor and the female protagonist of the film, in the blue, storm-rippled Lake Como. He keeps on a t-shirt to elude all questions anyone might have about his arm, which he twisted when he fell in his childhood from a rooftop in Jaipur while chasing a kite. A herd of camels in the Thar Desert. Irrfan is playing a camel trader in this film. He calls out, “Baba!” And Patang trots over to him and lowers his head. Irrfan’s hand on Patang’s face.

This ferocious flow of memories — is this the final savour and succour of friendship? It’s a celebration and an elegy. But what’s the source? Is it my grief that opens the dam? Is it a gift or a curse? It flows, spills, answers. There are no answers. Nothing is lost and yet everything is lost. I do not remember the before and the after. Forgetting is with every word. Chairs, couches, the floor, the sand, the grass that we sat on, the drinks that we shared, they fade. Yes, the flow shimmers with some memories and wipes out other moments. If that’s it, then so be it. I’m convinced, though, that the undulations of the time lost remain.

This flow of memories, I’ll hold on to it like a talisman, caress it, breathe on it, speak to it. If only it will keep Irrfan alive. For a while longer with me.

*****

Excerpted with permission from Irrfan: Dialogues With the Wind, Anup Singh, Copper Coin. The book hit the stands on February 14.