Like every bookish kid, I spent a good deal of my free time reading novels by Agatha Christie and PG Wodehouse. The two worlds rarely met – Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple were single-minded, hard-nosed detectives digging up skeletons in family closets, while Bertie Wooster only occasionally paused to read a mystery novel between visits to the Drones Club and dinner with his Aunt Agatha. Never did the possibility of the two meeting – a crossover episode, if you will – strike me.

Ah, but the crossover certainly does exist. The Lord Peter Wimsey series, by Dorothy L Sayers, is what you get if Bertie Wooster acquired the deductive abilities of Hercule Poirot. The younger son of a titled British aristocrat, Lord Peter nevertheless has plenty of money, a collection of rare books and Bunter, a faithful valet who takes photographs of crime scenes when he isn’t making coffee or laying out his master’s suits.

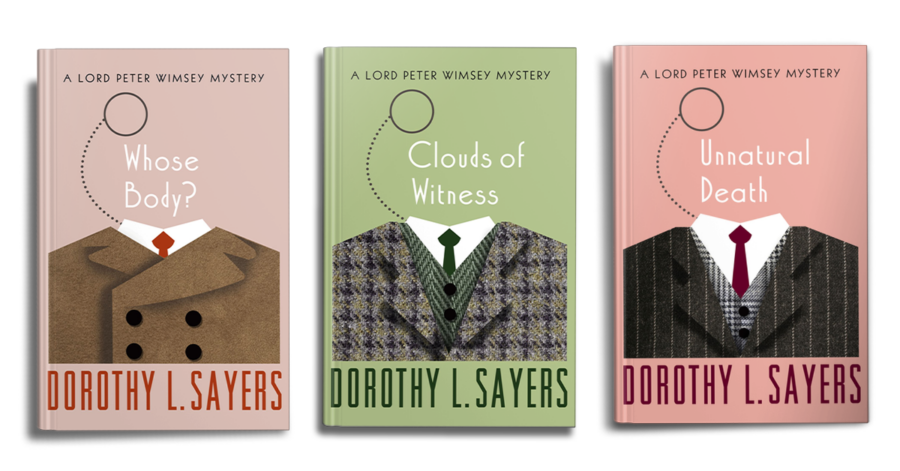

In the first book in the series, Whose Body?, published in 1923, he discovers the true identity of the man found dead in a London architect’s bathtub with a little help from Bunter and a bottle of fine port. Not long after, he clears his brother’s name after he is accused of murder in Clouds of Witness and saves mystery writer Harriet Vane from the gallows in Strong Poison, before solving his very last mystery in Busman’s Honeymoon.

The mysteries themselves have enough action to keep you glued to the edge of your seat. Lord Peter does not have Sherlock Holmes’ DIY chemistry set or Miss Marple’s careful analysis of human nature. Instead, he relies on flashes of insight, aided in no small measure by his compendious knowledge of literature (see Strong Poison, for instance), his considerable financial resources and social capital (Clouds of Witness) to solve the most confounding mysteries, with enough time to spare for lunch at the Bellona Club.

Now, this does mean that the Sayers’ mysteries aren’t quite as neatly tied up as some of the more famous detectives. But as one commentator notes, Sayers makes up for this with a deep awareness of class and gender divisions in interwar England. As with her Montague Egg series, the mysteries often turn on social class and what is expected of those occupying them.

In the very first book, Lord Peter remarks that he pays Bunter “200 pounds a year to keep his opinions to himself.” This would be unremarkable if Lord Peter did not also spend nearly four times the amount on an old book in the same paragraph. For his part, Bunter is revealed to be a veteran who served under Lord Peter in World War I and nurses him through periodic episodes of shell shock.

Recommended

Written three years later, Clouds of Witness presents a well thought out commentary on the “honour” and decorum that the landed gentry was expected to maintain. A good part of Gaudy Night turns on how women were perceived in the inter-war years; those, like Harriet Vane, who choose to have sex outside of marriage, and those who forgo even the option of marrying to keep their jobs in a university. Sayers’ novels were as much a commentary on upper-class society as they were cosy detective stories.

Lord Peter Wimsey is the sort of detective you don’t see too much of in today’s fiction. He comes from a time when you didn’t need a great deal of scientific or forensic knowledge to solve mysteries, just occasional strokes of genius and a few lucky accidents of birth. It’s not a world I wish still existed – but it makes for some great storytelling all the same.