Oliwia Dabrowska, the Polish child actor who played ‘the girl in red coat’ in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), recently went viral on social media for aiding refugees fleeing the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In a conversation with Silverscreen India, the self-employed copywriter says her casting in the 1993 film about the holocaust was an accident, but her decision to help the Ukrainian refugees was an obvious choice.

“I am against war, in any case. And I couldn’t stay and do nothing when such a big group of people needed help,” she says.

Dabrowska had auditioned for the role, after her mother had come across an advertisement in the paper. She was accompanied by her grandfather.

“I was in this group of girls, and Steven Spielberg chose me. I guess because I was open, bold. I wasn’t shy, I wasn’t afraid. Also, I had bright eyes and blonde hair, and they wanted a girl who looked exactly like that,” she says.

Now, 29 years later, Dabrowska is in the spotlight again, in the midst of a real-life conflict this time – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. She tells us that she has helped over 10000 Ukrainian refugees in association with the organisation GSR UA.

A friend encouraged her to channel her anxiety about the situation into aiding the refugees, and Dabrowska thus began volunteering on February 28, along with her mother.

Their first action as volunteers entailed the transport of refugees from the Polish-Ukrainian border to safer cities inside Poland. “That was the most important thing, then, because there were a lot of refugees but buses weren’t plying and there wasn’t any help from our government, either. The refugees had no options to even commute to the nearest city in Poland,” Dabrowska says.

“Secondly, I joined a group that looked for homes or temporary accommodations for the refugees. I would call a lot of people, check several Facebook groups. I had to spend hours to just check things and search on social media. This was very tough,” she adds.

It was only after she started working with GSR UA, a foundation for refugees, that she decided to use her image from Schindler’s List “to get people from around the world involved.”

However, the idea to do so was not Dabrowska’s own. “I had only started posting about my work, on Instagram, when one of my followers sent me an artwork, the image of the girl in a red coat from the film in blue and yellow print – the colours of Ukraine. We talked a lot and it was his idea to use this image to promote the Ukrainian cause,” she says, and adds that the wider circulation of the image only happened after the American media covered her story.

She now spends much of her time writing, putting out Instagram stories, and giving interviews. Her phone rings 20 hours a day, seven days a week, she says.

Dabrowska has over 33000 followers on Instagram, at present. “Because of this, I am able to contact more people. A post this popular, with these many likes, will be viewed by more people and this is how we can put social media to use,” she says, adding that many of her followers have offered her aid – financial, material, as well as volunteering.

As for her own volunteering efforts, Dabrowska credits her organisational skills, that she has inherited from her mother, with helping her efficiently aid the refugees. She shares an instance where she was able to arrange insulin in bulk, just by connecting volunteers.

“My mother and I were receiving a Ukrainian volunteer from the airport. During our conversation, she said that she had money to buy insulin. But, in Poland, one cannot buy insulin without a prescription from the doctor, and even if you have one, you can only get it for one person. But she wanted to buy insulin in bulk because there are many refugees with diabetes, who don’t have medical help. I had a contact person (from our group) who works as a pharmacist. I connected those two women, and that’s how I was able to arrange insulin for diabetic Ukrainians.”

In addition to working for GSR UA, Dabrowska is also a part of a volunteers’ WhatsApp group with over 200 members.

“Everyone (on the group) has their own ways of contributing. Someone’s a driver, another is a doctor, someone else is a part of an organisation like I am, another is ready to volunteer at the border, someone has a place that they could rent out, while some others find financial resources. That is how we do it. Also, we regularly search Facebook groups, and call whoever we know, and this just keeps getting bigger,” she tells us, recollecting the days when volunteers transported over 200 people in a day, either by private cars or buses provided by the organisation.

But just manpower is not enough. “The biggest requirement is money, to be honest,” Dabrowska says.

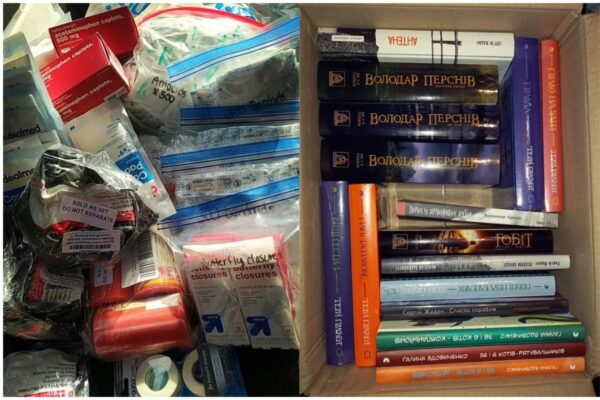

In addition to buying food, and paying for rent and fuel for refugees, money can also help Ukrainian soldiers, she says. “What is needed and what we cannot buy in Poland is medical assistance and equipment for Ukrainian soldiers. We want to send them bandages and painkillers, because they do not have all of that in Ukraine anymore, and in Poland, we need to wait for shipments to arrive.”

Arranging aid for the Ukrainian refugees has left the self-employed Dabrowska with little time for work.

“I didn’t work last month. But my husband works, and even though it’s not enough, it is okay. Because right now, I am focused on one thing – helping the refugees, and my husband has been supportive of it.”

Recommended

There has been a shift in Dabrowska’s focus these days, as the number of people at the border has receded. The challenge now lies in the cities, where people have sought refuge. “It looks like they will be staying with us for a long time, and temporary homes are not a solution. Now, we need to take care of them, we need to find them long-term apartments. We need to help them with finding jobs, schools for children, help them learn Polish. We also need to obtain funding so we can offer medical help to those who have illnesses. It is our responsibility to take care of them.”

Giving due credit other countries like Bulgaria and Moldova, which have also lent a helping hand to the refugees, she adds, “After all, they (the Ukrainians) are our neighbours. I am sure that they would have done the same thing for us.”