Theatres are still shut in Kerala and the footfall in Tamil Nadu theatres has been underwhelming since reopening in November. None of this is surprising, after the first countrywide lockdown in March, the Covid-19 pandemic has only raged across the country bringing with it its own set of crises and political apathy. Cinema took a backseat and industries turned towards OTTs to make a quick profit. It could be endlessly argued if OTTs became a dumping ground for films that were expected to fail at box office (especially in Tamil as they the trend began with Ponmagal Vandhal and Penguin, both forgettable) or it is a legitimate future route for cinema to take, especially a particular kind of cinema. Nobody can define that kind, right now it is a wait and watch scenario as more OTT releases are on the cards with no updates on the previously marquee films of 2020 – Lokesh Kanagaraj‘s Vijay and Vijay Sethupathi starrer Master, Karthik Subbaraj‘s Jagame Thandhiram with Dhanush and Ajith fans still waiting on Boney Kapoor to know what is up with Valimai.

More importantly, the big films are waiting for theatres to go back to 100% occupancy and for the distributors to find a way to cover all the major regions. A watershed moment was of course Suriya‘s decision to release his film with Sudha Kongara, Soorarai Pottru, on Amazon Prime Video. Its long-term effects are anybody’s guess.

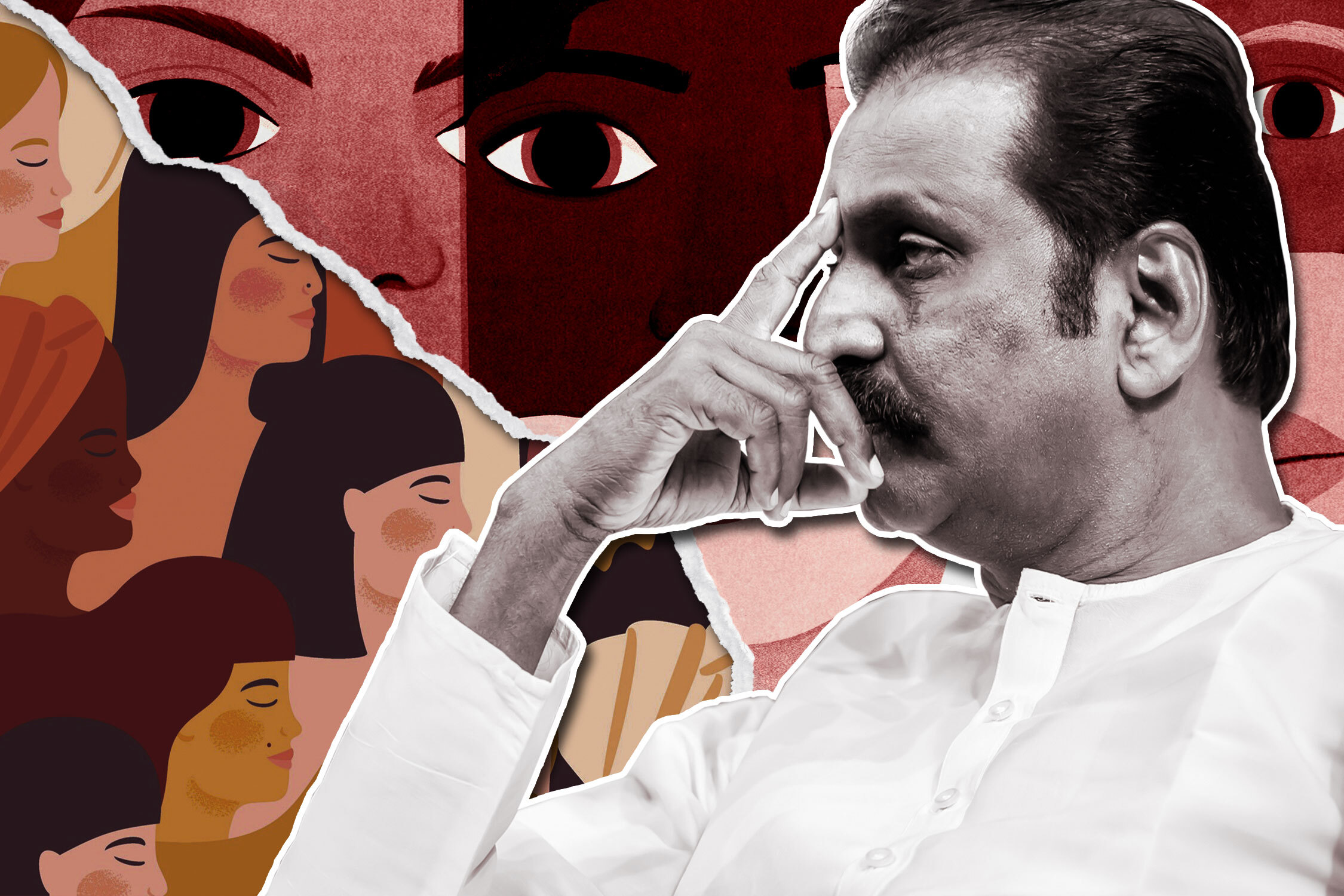

With the pandemic on one side and the OTT debate on the other, 2020 was stretched thin. After a string of films where the subaltern asserted their place in Tamil cinema, a trend began to develop where other producers and filmmakers wanted to get on the train as well, the marginalised subjects that could be mined for telling stories hitherto never attempted in Tamil cinema. If done well, it’s a welcome move. It’s not so welcome when the message supersedes the medium of cinema, as Tamizh Prabha observed, in the cases of Gypsy, Ettuthikkum Para and Kanni Madam. But this trend – that began a decade ago and gained new vigour with the arrival of Pa Ranjith – brought with it films that also push back, that reaffirm caste pride and hegemony – in the cases of films like Devarattam (2019) and Draupathi (2020). And to close off 2020, we got Netflix’s long-awaited anthology Paava Kadhaigal, with four top filmmakers basing their films on caste-based killings, gender, sin and pride.

On that note, here are the five films that piqued my interest from 2020, not ranked in any order.

1. Dharala Prabhu

Krishna Marimuthu‘s remake of Shoojit Sircar‘s Vicky Donor is a faithful one, even managing a touch of authenticity of its own with some minor, effective changes. It is in large parts thanks to Vivek, who brings with him his long-lost siblings – sarcasm and wit – as Dr Kannadasan to the role played desperate and funny by Annu Kapoor in the original. It is impressive that Krishna retains all the complexities of the source, not mincing the harsh truths, a choice that would have made the Tamil version a straight shooter by simply adapting the plot line. Instead, we get a dignified love story, some great buddy comedy between Harish Kalyan, Vivek and RS Sivaji, along with some interesting ruminations on adoption or same-sex couples looking to start a family, all purely through visuals rarely seen before.

(Read the Silverscreen India review of Dharala Prabhu here)

2. Sethum Aayiram Pon

For a film around death, Anand Ravichandran‘s Sethum Aayiram Pon is always mobile. It played at festivals in 2019 but released on OTT in April 2020. The film revolves around a city-bred Meera aka Kunjamma (Nivedhithaa Sathish) – a make-up artist in the film industry – returning to her village for the first time as an adult to meet her grandmother Krishnaveni (Srilekha Rajendran), an oppari singer. The film possesses beautiful mise-en-scène, long takes garlanding a funeral and Anand’s roving camera catches all of it in constant motion. The conversations filmed in wide angles gradually panning closer as the characters share personal moments, in turn becoming intimate are particularly memorable. Sethum Aayiram Pon also has a musicality about it, almost every character has a job associated with rituals following death, their language turns lyrical without so much as a warning and it only accentuates our experience of getting to know them better. The whole film is like watching the evolution of something like Makka Kalanguthappa, as if death has come to life in celebration of itself.

(Read the Silverscreen India review of Sethum Aayiram Pon here)

3. Soorarai Pottru

Sudha Kongara gave an alternate history of Air Deccan founder GR Gopinath, but she made it so kinetic and immersive that nothing else seemed to matter. Her characters raced along with the screenplay, be it Suriya’s Nedumaaran or Aparna Balamurali‘s Bommi. What was expected to be romance turned into a duopoly where two characters with high flying dreams and similar, restless energies raced against each other to pip the other to the post. It gave us a buoyant relationship drama along with a story of another assertive character who is an ally of the marginalised, using his dreams and capitalist acumen to uplift a whole demographic. Sudha’s film could be politically fragile but the filmmaking and performances more than make up for it, turning Soorarai Pottru into one of the best joyrides in a mass movie in recent memory.

(Read the Silverscreen India review of Soorarai Pottru here)

4. Oor Iravu

Vetri Maaran‘s contribution to the Netflix anthology Paava Kadhaigal is an illustration of why he is current Tamil cinema’s foremost mainstream auteur. Oor Iravu might be a story of a father and a daughter, played by Prakash Raj and Sai Pallavi respectively, but there is a lot happening around them. Its denouement might be predictable (even by design if you go by Netflix’s recommended order of viewing the anthology) but it captures in essence the other side of a caste-based killing. This is the point where most narratives of similar nature end. What happens when a couple momentarily elope and escape to freedom? How do people in her family perceive this development? We hear snatches of those conversations and reaction at Sumathi’s claustrophobic house teeming with men and women who claim their lives were run awash by her. Their misplaced fight for supremacy is now reinforced with a fight for survival. And using a mix of tracking shots, high angle (as much as that house would give him) shots, light play and ambient sound, Vetri manages to build tension and depravity into a closed chapter.

(Read the Silverscreen India review of Paava Kadhaigal here)

5. Nasir

Arun Karthick‘s Nasir did not get a permanent release, but it played as part of Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival’s Year-Round Programme for everyone in Asia to watch and once again as part of the line-up in the global ‘We Are One’ film festival when the world’s top tier festivals joined hands in the time of the pandemic. Nasir‘s super 16mm 4:3 footage gives a glimpse of the narrow confines that an Indian Muslim lives through in present day India, a quasi-Hindu rashtra. Nasir is a mood piece that might be uneventful, which is a feature – what’s a day for Nasir like from dawn to dusk? Arun paints the grim reality of a Muslim man’s struggle in a place where the Hindu far right claims its authority over all things India. Koumarane Valavane plays the protagonist with a dispassionate zeal for survival, his concerns only around his family – his wife, his work, his debts. The brilliance of Nasir is in its muted documentation of all forms of violence – verbal, physical, mental – and how the surrounding atmosphere enables it, what people really think deep in their hearts, their contradictions and hypocrisies in a supposedly pluralistic society.

(Read the Silverscreen India review of Nasir here)

Honourable Mentions: V Vignarajan’s Andhaghaaram & RDM’s Kavalthurai Ungal Nanban