The most controversial figure at the moment, financier Anbu Chezhian, has been a regular at movie events. Video clips on YouTube feature Anbu speaking at various meets; at the Pandiya Naadu audio launch, Anbu, in whites, calls the film “colourful,” and heaps praises on the cinematographer and the movie’s hero Vishal. In another video, he’s described as a “leading financier and one of the biggest producers” in Kollywood, and is asked for his opinion on the fate of a new release – a Dhanush movie.

But, chances are that if you pass by Anbu Chezhian, someone who is said to be ‘running’ the industry from behind the scenes and someone with whom almost 90 per cent of the industry has had financial transactions with, there wouldn’t be an instant spark of recognition.

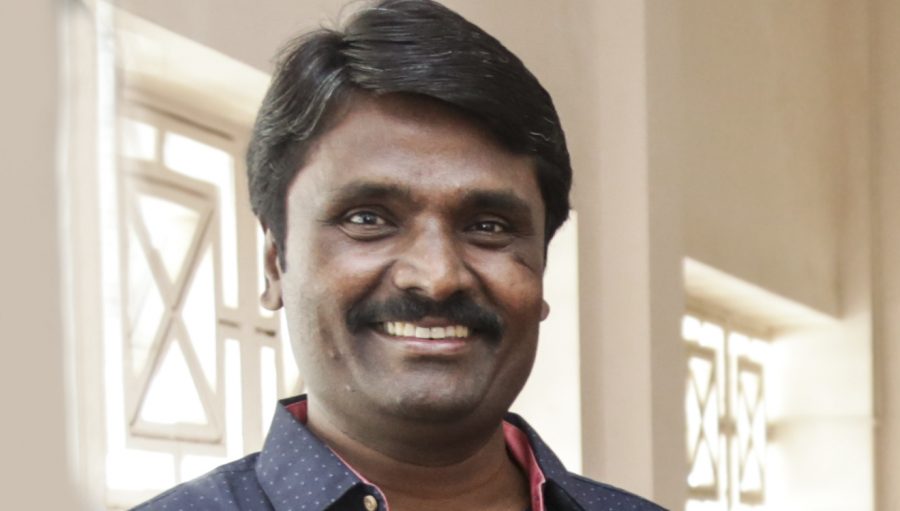

It’s not hard to slap an age on Anbu Chezhian, currently the much-reviled and vilified man in the Tamil film industry. In most of the photographs circulated online, his hair is dark with a slick side parting. In one picture, it poufs over his forehead; gelled and decidedly well-behaved. It makes us almost jealous; hair serums work, of course, but such impeccable hair discipline is hard to achieve. Except in the movies.

But, Anbu IS the movies.

And, according to several reports and accounts that have now surfaced, he is the cogs that set the wheels of the entire Tamil industry in motion. That, anyway, helps only little by way of ageing him. A couple of recent reports peg him at 50, but one that truly identifies him – and adds character while at it – is dated around 13 years after he began his business; a 2011 The Hindu report mentions Anbu alias Anbu Chezhian (43), son of Neelamegam, who was held along with accomplices on charges of conspiracy and attempt to murder. The petitioner, then a couple of years older than Anbu, is said to have borrowed Rs 20 lakhs to fund his movie Meesai Magan in 2004; he had turned over signed stamp papers and blank cheque leaves which weren’t returned even on payment of Rs 1 crore as interest.

The story, which would have perhaps been buried under regional news in the city editions, ends with an appeal by the then Superintendent of Police, Asra Garg, to bring to the cops’ notice, “instances of people charging high rates of interest called ‘metre vatti’, ‘run vatti’, ‘kandu vatti’.”

Anbu, right now, is front page news in most dailies, the leading story on most websites, and is seen across screens on regional language channels that seem to have scheduled debates by the hour. A Thanthi TV presenter talks in earnest about Anbu’s beginnings. The financier, who hails from Ramanathapuram, had arrived in Keerathurai, Madurai in 1997, in search of sustenance. After a string of odd jobs, he had loaned Rs 5,000 he had, on promise of timely interest payments. Soon, he had struck a profit margin, began lending to distributors (or “cinema petti thookuvor” – a reference to the time when the reel of the movies would arrive in huge aluminum cases) – and then grew enough to provide funds to buy film reels. “He would travel on a cycle to collect the interest owed to him,” the reporter says, “but later, as his fortunes changed, his ‘nadaimurai’ (methods) did too.” He is then said to have expanded his business to Chennai, became popular in film circles after lending to cinema caravan owners. “His style was all about getting to know a film, its director, and offering financial help to the producer with their property as collateral.”

The presenter then declares that after launching his Gopuram Films, he had his eye on an AIADMK seat in the last Legislative Assembly election, but his political ambitions came to a nought as then Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa was unhappy about the intelligence she received about him.

A Vikatan TV news segment calls Anbu a ‘kathanayagan’ (hero). “Someone who had humble beginnings; he began by lending to small-time businessmen in the Madurai areas of Central Theatre and Vilakkuthoon, and then grew to become a financier who would turn over the required fund even while listening to a film’s story. But, he also obtains signed sheets, and goes after the properties of defaulters.” The 2011 The Hindu article mentions that Anbu had allegedly conspired with R Murali to register the petitioner’s immovable properties in their names.

Last evening, R Murali, on a letterhead of Gopuram Films, had sent out a press release questioning the veracity of producer Ashok Kumar’s letter, which he is said to have written just before killing himself. “We had no financial transactions with Ashok Kumar,” the letter reads, “We were only dealing with his cousin Sasi Kumar. Is there proof that the note was authored by the producer?”

Vikatan TV, meanwhile, ends its character sketch with a footnote about Anbu’s family. He has a son whom he cut ties with, the reporter says, “because, he married a Dalit woman. Anbu is currently looking out for a groom for his daughter.”

His father – Neelamegham – was apparently a teacher.

*****

While most of the film industry, led by TFPC President Vishal, speaks in turns against the financier denouncing his unjust interest rates, trade practices, and most of all, his reprehensible ways of dealing with defaulters, a few voices have come out in support of the financier. Director Seenu Ramasamy, actor Vijay Antony and producer Singaravelu, on different media, have spoken in favour of Anbu.

Antony, in a press release, describes his dealings with him. “For the last six years, my movies have been financed by Anbu Chezhian,” he writes, “I have never been a defaulter and I have been diligently repaying my interests. He has been good to me. I think he’s being portrayed in a bad light. In this industry, 99 per cent of producers and actors make movies by obtaining loans. I have loans too, and I am paying them back.”

On the debate hour on NEWS 18 – ‘Kalathin Kural’ – producer Singaravelu, amidst several voices of dissent, elaborates on his encounters with Anbu Chezhian. He describes an instance involving actor Vimal, who is currently producing Mannan Vagaira. “We financed the project,” explains Singaravelu, “We were told that the movie would be wrapped up within Rs 3.5 crores; it was not the usual rendu paisa, moonu paisa agreement (2 per cent, 3 perc cent interest rates), we asked for 10 per cent on the profits when the film releases. Everyone signed the agreement including the director. But, the budget has already crossed Rs 7 crore, we have lent Rs 6 crore as of now, and the movie is not done yet. Right now, we wouldn’t get what we had discussed, instead we’d incur a loss of Rs 1 crore, but we waived our dues this time and told Vimal that he can pay when his next movie releases.”

Singaravelu then says that he’d asked Vimal if he had any other loans as financiers are usually silent till the day of the release, and spring to action only on the scheduled Friday. “Vimal then revealed that he had acted in a movie called Jannal Oram in 2013, but there was no money to release the film. He had then called Anbu who had immediately settled the dues and paid Rs 75 lakhs without any papers or surety. Vimal began paying interest, but he is not doing too well in the market. Right now, it has been three years since he paid any interest.” We then decided to meet Anbu Chezhiyan, says Singaravelu. “He received us well, and told us that current dues amount to Rs 1 crore and 40 lakhs. He was willing to waive 20 lakhs. We worked out an agreement and Anbu then called the ‘federation’ and told them not to halt the release of the film.”

“Rajini Murugan had encountered the same fate,” Singaravelu adds, “But Anbu, after watching the film, waived what was owed to him. For Mottai Shiva Ketta Shiva, an amount of Rs 45 crores was borrowed; the movie had made only Rs 17 crores and Vendhar Movies’ Madhan had left the city. Anbu then called for a meeting and told all financiers to waive a little of what was owed to them. Almost 60 per cent was waived on the principal amount.”

Recommended

If there are 200 movies releasing a year, 30 big movies are financed by Anbu, Singaravelu says, “three releases a month belong to him.” Also, producers turn to Anbu Chezhian because of his ‘speedy settlements’.

Financiers are not the only reason a producer is in trouble, Singaravelu declares. “For instance, take Sathuranga Vettai – Manobala is producing it; he borrowed money from Anbu, but they overshot the budget. They couldn’t pay Arvind Swamy. And right now, the movie is on hold because Arvind Swamy has said that unless he is paid the Rs 1.5 crore that is owed to him, he will not dub for the film.”

Sasikumar’s market value is Rs 5 crores, reveals Singaravelu just before the show ends, “he could have repaid the loan with four films…”

*****