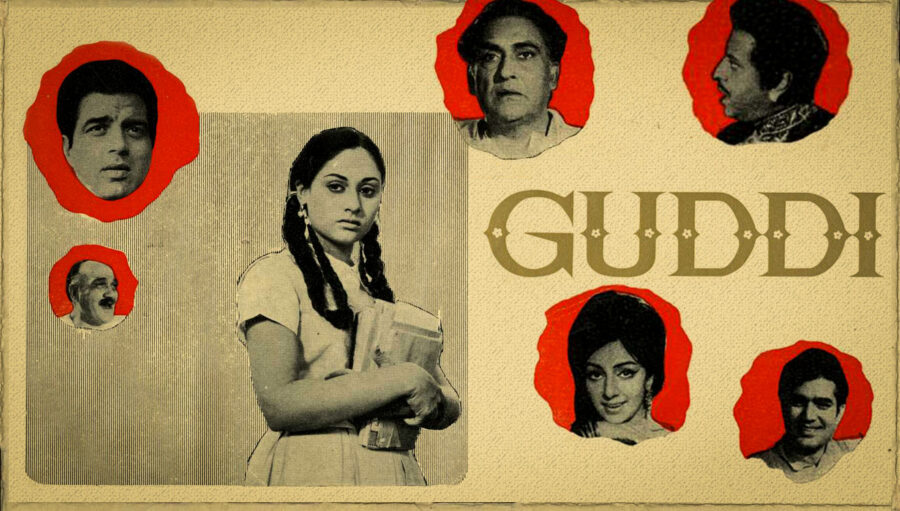

In the 1960s, ‘beehive bouffants and dramatic eyeliner were the norms of the day’ as Dinesh Raheja points out in this piece. So, ‘when fresh-faced, scrubbed-clean’, young Jaya Bhaduri first appeared in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Guddi (1971), not only was she welcomed for her un-conceited aesthetic, as Dinesh says, but also for being a performer who would outshine even the most seasoned of actors in the frame with her sheer earnestness.

As she celebrates her 72nd birthday, today, I revisit one of her most endearing roles.

One way to read Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Guddi (1971) is as a film on love, about love for cinema. It is the story of a vivacious teenage, school-going girl, Kusum (Jaya Bachchan), fondly called Guddi, who has a crush on and is obsessed with the superstar hero of the Hindi film industry, Dharmendra, who plays himself in the film.

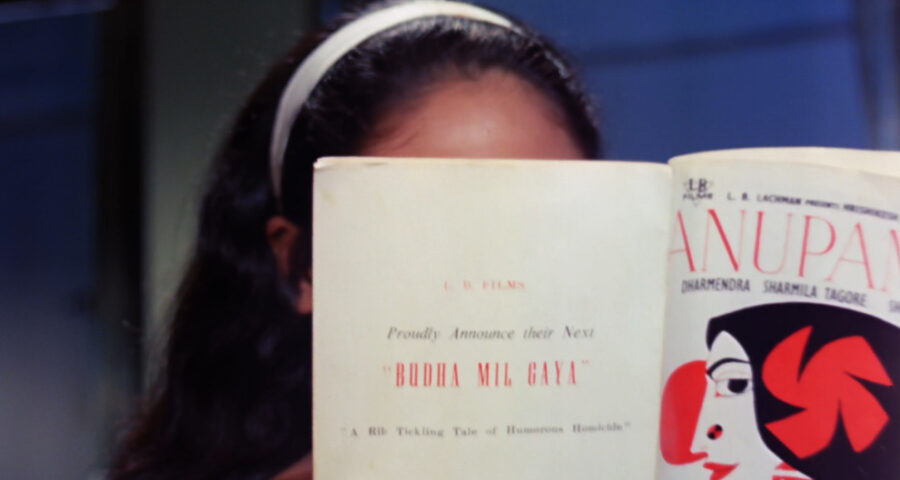

As a commentary on the culture of the deification of Hindi film heroes, the film is a splendid self-examination. Interspersing visual and aural material like billboards, film brochures, shooting, and behind the scenes footage, the modest Guddi joined an ambitious league of meta films. But what made the film memorable was its discovery and rare exploration of the eroticism of the female spectator’s cinephilia.

Guddi begins with the scene of an early morning assembly in a school. The students are singing Hum Ko Mann Ki Shakti Dena, a prayer asking God to grant them good sense to overcome temptation. The prayer and other songs in the film were sung by Vani Jairam, who curiously went on to be called the Mira of modern India. Kusum is late for the assembly but begins to lead the choir just when the stanza imploring the Almighty to keep them from falsehood, overcome the pleasure-seeking self, rescue them from going astray and lead them the path of dharma features. The concept of dharma is also gendered and, here, it portends to instill the norms of sexual purity among these young girls of ‘marriageable age’. After the prayer is over, Kusum is asked to explain why she’s late. She makes up a story. Outside the principal’s office, she feels no guilt whatsoever, in fact, boasts of her tour de force, to her friends, comparing herself to Meena Kumari – “What is a lie after all but good acting?”

There could not have been a better entry point into a film that explores the idea of cinephilia, reality and fiction, truth and falsehood. It is clear that the kind of cinephilia that Hrishikesh Mukherjee aimed to produce is of a love for cinema, so profound that not only had it integrated seamlessly into one’s daily life, but had become a way of life itself.

Kusum’s conversations with her friends revolve around films – the films they have watched, and the films they are going to watch after school. They call their celebrity crushes by their first names and talk about them like they’re talking about ordinary boys. A classmate talks about how another had nursed a photograph of Jitendra, by adding wet bandages to the forehead of his picture on hearing the news of his sickness. This guiltless, pleasure-borne exchanges of adolescent desire in these scenes reminiscent of “chick-flicks”. The classroom talk brings to our attention the existence of a female spectator of the Hindi film that had been seen as an insignificant minority.

Kusum’s act of going to the movie theatre with her school friends does not invite rebuke from her family. It is accepted as a leisure activity almost as normal as her going outside to play with her friends. It is a pleasantly liberal position given a historical situation, as my mother, also born in the 1970s would tell me about how her father permitted her to go out to eat with her friends but was vehemently opposed to girls watching films, as films were said to corrupt the naïve mind of girls.

Love Love Love

Guddi brings alive an engaged, and eager relationship between the female spectator and her onscreen hero. When Kusum looks out of her taxi in Mumbai, the many, multi-coloured billboards of films call out to her, asking her to Love, Love, Love! The song ‘Pyaar Pyaar Pyaar’ (Love Love Love!) which plays in the background in Mohd. Rafi‘s voice addresses the hero as the “khidmatgaar” or entertainer, assuring her and the whole race of (female) spectators, that as long as he was still alive, he would always be disposed to please them. Abhi salaamat, Abhi hai zinda, Aap ka khidmatgaar/ Aap ki khidmat mein haazir hai, Leke pyaar hi pyaar.

However, the film soon shifts gears to establish that pleasure is not the only emotion at the heart of this relationship, there is also reverence. Possibly because its sole entitlement would have been too anarchical for the times. So, one by one, institutional agents come in to appropriate and redeem this form of cinephilia. First come Kusum’s teachers.

Guddi Mira2

After a lesson on the life of Mirabai, the Bhakti poet who defied her in-laws and social norms by devoting herself to Krishna whom she believed to be her husband, Kusum begins to fashion herself as Dharmendra’s Mira (even literally, as she refuses to wear a silk saree that her sister-in-law gives her, citing “sacrifice” as the reason for her choice). She relates to Mira’s poems so deeply that she begins to articulate her feelings through this projected self. The same concepts of “truth”, “power of God” and “the self” that she sang about in the morning prayer, and learnt in her classroom lecture, now assume new meanings.

Dharmendra, her beloved, is now also her god. As Professor and art-historian Woodman Taylor observes in his essay, “Penetrating gazes”, her imagination of a union with Dharamendra on the lines of Mirabai’s poems is an appropriation of historic poetry to frame a love scene on the screen. “Mira’s poetry in praise of Krishna is normally sung in religious contexts during a religious, visual transaction of gazes called darshan, but Mirabai’s bhajan is used in the film to frame an imagined relationship on the screen, of Kusum longingly viewing the film image of Dharmendra. Here, a song intended for darshan viewing is now used for viewing a lover [through nazar, the erotic gaze of the Persian poetry].”

Film scholar, M Madhava Prasad writes in Ideology of The Hindi Film that, Guddi was “intended by Hrishikesh Mukherjee to critique popular film culture and to unmask what he considered to be an illusionary ’reality’ constructed on the screen by Bombay film companies.” This task is carried out in the film by Kusum’s uncle, Professor Gupta played by Utpal Dutt.

When Gupta realises that Kusum has gone off track, he takes no time to figure out that the way to bring her back was to get her to see the “reality” behind all that filmy façade. Through a brilliant allusion to shadows in Plato’s caves, he assures Navin (Kusum’s sister-in-laws’ cousin and the approved match for Kusum), that once the “parchhaiyaan” fade, Kusum would be over her infatuation.

6a00d83451bfe269e20133ef516124970b-600wi

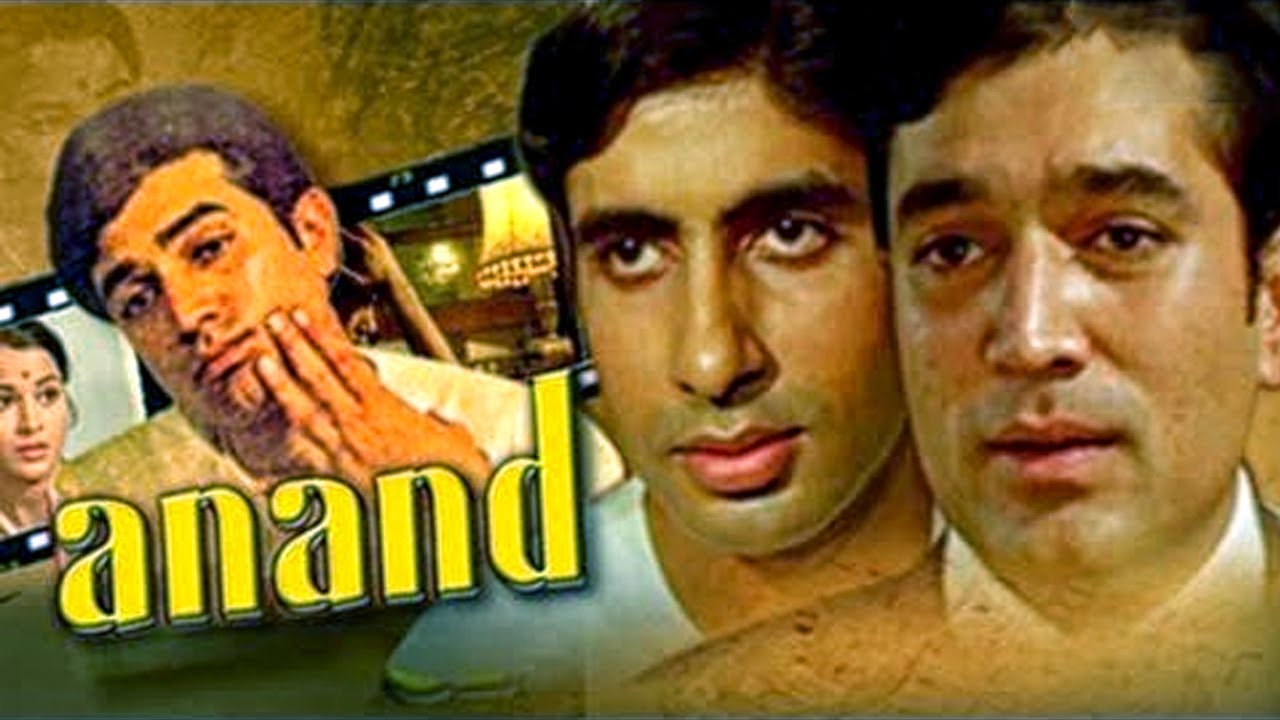

So, he hatches a plan that involves the “actor” Dharamendra whom Kusum was obsessed with to shed his larger-than-life persona and allow Kusum to see his “real self”. As part of the plan, Kusum and Navin visit the film set every day to spend time with the “real”, off-screen Dharamendra, and in the process become faced with the challenges, the struggles and the harsh verisimilitudes of the film industry. As the enigma unravels, Kusum learns of the non-glamorous job of the director, writer, stuntmen, camera crew and production staff, “the real heroes” who run the show behind the scenes, while the actor plays the royalty and enjoys the fruits of others’ labour. This sequence is also a joyride for the audience as one contemporary male superstar after another, from Pran to Amitabh Bachchan to Rajesh Khanna, make cameos. This sequence is also one of the most established parts in the film where the filmmaker reclaims control of the narrative back. The position of the film, vis-à-vis the deification of the Hindi film hero becomes more and more apparent.

In one scene, a light man faints and hurts himself. As a kind gesture, actor Om Prakash hands one hundred rupees to the in-charge to give to the injured worker. In another scene, Dharamendra, launches a tirade against a magazine photographer for propagating a culture of hero-worship, but the photographer turns around to remind him that despite the perverted nature of the work, he had a family to feed. The character of Kundan, Kusum’s neighbour who steals from his old mother and runs away to Mumbai on the false promises of becoming a hero is an emphasis on the many falsehoods that keep the industry running.

In another sombre scene, Navin asks Dharamendra how he managed to remain sane in the glamour world. Dharamendra attributes his humility to his simple rural roots. Even Dharamendra’s onscreen name is a persona, not his “real” name.

Through these instances, the actors are still deified, but now the emphasis is on their magnanimity, benevolence and humility despite their elevated status. And this is where Guddi falters. What could have laid the seeds for a new, beautiful, and homegrown cinephilia, driven by the female gaze, (a term that was yet to be invented by Laura Mulvey in 1975) is replaced by a traditional and pedagogical one with male agents. In all of these charades, Guddi’s active viewing position changes to dormant.

Then, a more critical way to read Guddi is as the story of a teenage girl’s family, who plot to arrange a traditional marriage for their daughter, by first purging her love for the movies and heartthrob, actor Dharmendra.

Recommended

Under the (benevolent, patriarchal) garb of protecting her from madness, by showing her the truth, her uncle actually only feeds her lies and manipulation. A script is still being written, a stage is still being set, and Guddi still remains a spectator, watching the shadows move before her, as a “reel” hero is replaced by a “real” one. As Dharamendra’s larger-than-life persona is dismantled, Prof. Gupta creates Navin in the same image. Kusum is won over by his chivalry, his generosity, his charm, and finally even his bravery. She cannot get over how Navin fought the goons and protected her just like a filmy hero.

In one of the last scenes in the film when she secretly reads Navin’s diary she gets into a dramatised monologue about the real versus fiction, except that the experience she is reciting is not hers.

What’s worse is that the film accomplishes the exorcism of a believer, so much so that by the end of the film, she’s repulsed by the name Dharamendra and everything film. As she urges Navin to take her she utters the words – I trust you. I have faith in you.

Guddi Misce

Guddi’s ultimate absorption into the shadows, occupying the same peripheral Mira position, as a new hero/man assumes the position of her god, also symbolically underlines Jaya Bhadhuri’s initiation into the industry of the hero which she tried to shake but ultimately could not entirely uproot.