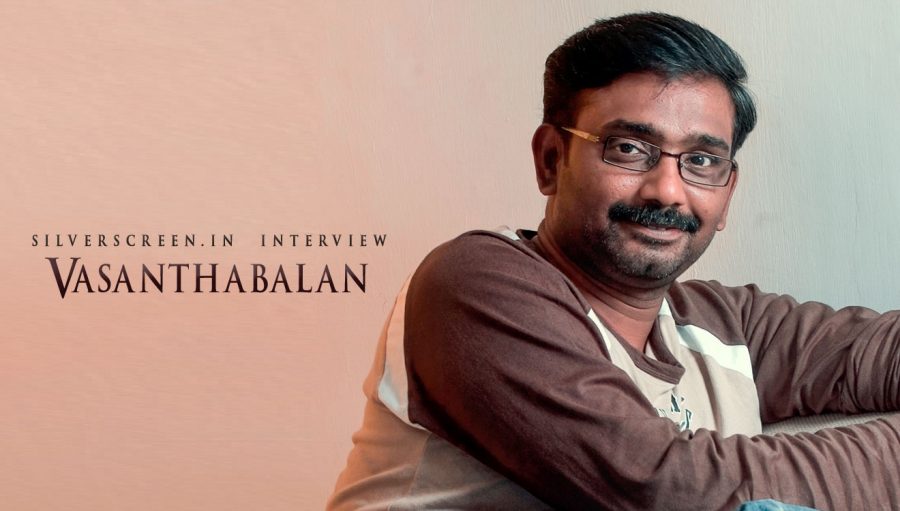

Sixteen years, six films. Sounds like an inconsequential number till you go back and peel the layers of Vasanthabalan’s filmography. If you skip his debut Album, the others have all put hitherto unexplored characters and areas under the spotlight. When history judges him as a filmmaker, it might not see him as a hit machine, but as someone mellow, who painstakingly etched creations for the big screen. For Vasanthabalan, that’s the biggest reward

Even after all these years of watching movies, award-winning director Vasanthabalan can’t digest artificiality in cinema. He respects it far too much to tolerate dressing, speech or behaviour that go against the grain of the character. “They’ll show a daily-wager wearing ironed clothes to the workplace or using lipstick. They will show you a filmy court set, unlike anything in reality. These don’t make for an immersive movie-watching experience. Every artistic creation must seek its truth. Because only when filmmakers embrace the truth will audiences allow them space in their hearts,” says the director who made his debut in 2002 with the middling Album.

He’s not entirely speaking without reason. “I have seen that truth pays through the successes I’ve enjoyed. I’ve seen it when films of mine that involve deep research have worked with the audience and box-office. What we know is but 10 per cent, there’s a vast unknown ahead. If we don’t research, we will come across as fake.” This love for research and reading took root in his childhood. At home, his mother, father and grandfather were into reading. “Thatha would get up at 4.30, and his reading comprised newspapers and the popular magazines of that time. Kalki, Kumudham, Ananda Vikatan… there was no shortage of reading material. My aunt would bind stories from magazines and read them. As a result of growing up in this atmosphere, I read Sivagamiyin Sabatham and Ponniyin Selvan when in Class 6 or 7. What this did was also introduce me to tasteful writing; it was difficult to read something that did not match this. I’d even call it an addiction for good literature.

…Later, when I would go to my grandmother’s house in Srivilliputhur for the holidays, books were my constant companions. I would head to the vintage Pennington Public Library there and spent time there from 8 am to 11.30 am, and back from 4 pm to 7.30 pm. I read Tamizhvaanan, and started writing poetry in Class 7. By the time I was in Class 10, I started writing short stories; when I completed college, I’d written over a 100 short stories,” he recalls.

These were handwritten using a blue ball pen, sealed in envelopes with a self-addressed return envelope and sent to various journals. Most of them came back. But, one managed a complimentary prize at a contest held by Dinamalar Vaaramalar. Later, as a student at the Virudhunagar Hindu Nadars Senthikumara Nadar College, a story written by him managed to win a gold medal, competing against 67 other colleges. The story was Neridum Neyam, an ode to his grandmother. “She was admitted at the local Government Hospital, and I would go visit her after school hours, every single day. I loved the reality of that space; every emotion was heightened…”

After assisting a director like Shankar, Vasanthabalan felt it was time to branch out. When Album washed out, he regrouped and delved into life in Virudhunagar for the searing Veyil. “The years following 2000 have been a treasure-trove of good cinema. It’s almost like a new wave. Luckily, I was around to make the kind of films I wanted to. Of course, we had to strike a balance. Unlike Europe, where theatrical earning does not determine the viability of a film and where people hold on to original DVDs like a family treasure, theatrical earning rules here, thanks to piracy taking away other avenues.

…A director can’t survive if his film does not do well at the box office. Or, you have to tie up with the National Film Development Corporation of India, which will fund artistic cinema and send it to film festivals here and abroad, but you will get only a limited theatrical release. So, how will it reach people? How will it illuminate their thought process? That said, over years, the audience has been groomed to expect certain elements in a film. And, if you ignore that totally, a film suffers,” says Vasanthabalan.

This nature of being drawn to reality comes from the director’s lived experiences. As a child, he worked in matchbox factories, fixed the lid (locally called chingi) on Kalimark cola bottles… the money earned was used to submit his stories to publication houses. “These were handwritten and would run to many pages; it would cost Rs 15 to send it, and I had to affix a stamp of similar value to the return envelope. They would unfailingly make their way home.” Today, these rejected stories sit in a rundown brown suitcase with torn sponge interiors. It has significance – it is the same suitcase Vasanthabalan took along when he ran away from home towards Chennai, where his dreams lay.

In many ways, Murugesan of Veyil was drawn from parts of a life that Vasanthabalan had lived. And, Kani of Angaadi Theru was the sum total of the many women Vasanthabalan had seen being molested in factories. Remember the scene where Anjali returns to her counter after an inexperienced colleague rats on her for not working hard enough and the supervisor summons her to a corner? The young boy laughs, wondering if the supervisor punished her. “He squeezed my breast,” she says, without emotion and walks; an unexpected punch to the audience’s gut. “I’ve seen the kind of issues women face in unorganised work spaces. They would tolerate such abuse, yell at the perpetrator or simply walk away. They did not have a choice. My team wondered if the scene would disgust people and stop them from investing in Kani’s life, but I felt it would work, and it did. After all, across work spaces, women have suffered sexual harassment over the ages, and continue to. I felt that this kind of realism would take films to the next level; that it is important if we have to move forward.”

Years after Angaadi Theru, the Kerala Government recently amended the Kerala Shops and Commercial Establishments Act to provide sitting facilities for employees. This is expected to help those working in jewellery and textile stores; till now, most establishments expected staff to stand for hours on end. “When the decision was made, some people referred to my movie too, and it felt like a vindication of sorts. In Raman Raghav, Anurag Kashyap inserted a reference to Angaadi Theru. So, it is possible to use films as a weapon for change. I believe films should be meaningful; the medium is that powerful.”

Veyil_poster

Similarly for Angaadi Theru, he was warned about the difficulty of shooting in a place of human concentration such as Ranganathan Street. “It came with a different set of issues. We could get permission to shoot only from 10.30 pm to 5 am. It was a challenge, but then how can one not showcase one of the top-10 identifiers of Chennai on cinema? We see the crowd, but they are not a lifeless mass; these are people throbbing with aspirations and desires. Who are they? That was what led to the movie. I decided to show what happens on the street at night, when all the shoppers have gone home, and when businesses have downed their shutters. There’s a face of an area you see, one you can’t and one in between. It is important to showcase all three. It was possible to realise that dream of mine only because of my crew, and producers Karunamoorthy and Arun Pandian of Ayngaran who released the film when they were in great difficulty. Looking back, I know that the film will occupy a space among the most important Tamil films made. It showcased lives that were never before seen on screen.”

Soon after the success of Angaadi Theru, Vasanthabalan began work on a magnum opus set in the 18th Century. Based on Su Venkatesan’s Sahitya Akademi-winning novel ‘Kaaval Kottam‘, it starred Aadhi, Dhansika and Pasupathy, among others. The film extracted a lot from its cast and director, and they gave it their all. Aadhi went on a diet for ages to maintain his look as Varipuli, and came up with a performance to remember. Vasanthabalan was crushed when it did not do well at the box office, but moved on, because “if you don’t, you’ll go mad”. This film was followed by the equally well-made Kaaviya Thalaivan, which met Aravaan’s fortune at the box office. The cast and crew were dejected, because it had entailed a lot of work. Years later, it would win nine awards given by the Tamil Nadu Government, and a clutch of awards at the Norway Tamil Film Festival. “I coped in the way I knew. I slept. God has been kind, and I can sleep away my dejection. My wife and children are my coping mechanisms; they give unconditional love. After a fortnight, I felt better. I knew I had done my job well, and that kept me going. Even today, when it is telecast on Vijay TV, I get calls and messages. That means something, illaya?”

Amid all this, livelihood suffered. Vasanthabalan says no one knows better why a hit film is important for a director. “Actors will move on to other projects. But, directors find it very difficult to find work after a flop. Even today, I wonder if I should have structured Kaaviya Thalaivan differently. Should I have made it a classic love story?

But, what allows me to survive is the knowledge that if Aravaan is an important movie to watch to know how 18th Century Tamils lived, Kaaviya Thalaivan brought alive a slice of the State’s theatre movement.” Making a movie is hard work for Vasanthabalan. He switches off completely from daily life. He does not read newspapers or magazines, avoids attending functions, and ensures he stays in the ‘zone’. “I can work from 9 am to midnight when I’m working on a film.” The filmmaker admits that while he has a strong bond with writing, he would like to direct what others write; or, at least collaborate with them. “We have novelists and short story writers. We don’t really have a culture of film writers. Once that becomes the norm, a director can just focus on his/her job.”

During interviews after Veyil and Angaadi Theru, the director wondered if he would ever be able to make happy movies. Has that changed now? “I don’t think so. My films revolve around life, and are steeped in the human condition. I can possibly write a light-hearted film in two days, but I don’t know if I want to. When you move settings from one film to another, and speak of a different category of people, you start from scratch, and it takes time to create their world and the people who inhabit it with them,” he says.

Inspiration for Vasanthabalan comes from varied sources. “Right now, I’m worried about Cyclone Gaja’s after-effects, there’s demonetization, NEET, Anita… society is a continuous churn, there’s unrest, the mind is not at peace… I can’t forget the aftermath of the 2015 Chennai floods. We were stuck at home and wondered how to feed our children. During demonetization, I had just Rs 500 with me, every day I waited in a queue. Every decision of the Government affects us. You feel suffocated. How can I forget all of that and write a lighthearted film?”

After all this, the director says he still does not bear a grudge against the audience for not appreciating his films better. “They thronged the theatres for Veyil and Angaadi Theru. So, I was happy then, I should not complain now.”

The film industry is an interesting space where a person can become rich overnight, and turn a pauper in the same time frame. When films don’t work out, directors suffer, and struggle to keep the home afloat. Some venture into the advertisement industry, and shoot a few films to keep the money coming. Some wait it out. Like Vasanthabalan.

Helping him were two friends, who kept sending him money, and insisted he focus on filmmaking. “My expenditure before marriage was not much. After marriage, I never turned extravagant. My friends Murugan and Varadhan kept me going. They were responsible for my doing well, and even today, they are around to support me. I’m the sort of person who can never ask anyone for money. At the age of 30, I was still not in a position to support myself. Luckily, I’m not the type of person who thinks success is in buying a car or a house. And, luckier still that my wife thinks like me. I’m happy in my space. Critical acclaim is not easy to come by. Some people earn money and fame, others just a name. I think I can add myself to the latter category. I’m happy to go to the tea shop on my Scooty, wearing rubber serrupu, travel second class by train, or board a bus without reservation with my children.”

Vasanthabalan says his life is proof of the circle of life. For Veyil, which was budgeted at Rs 1 crore, the team wanted to bring in Yuvan Shankar Raja. They could not afford him, and were looking for someone who could compose the songs and the background score for Rs 15 lakh. A PRO called Chandru brought along an album by a teenager called GV Prakash Kumar. “He was 17 when I met him. But he had immense clarity and enthusiasm. I thought I should travel with him. He’s a fighter, a Samurai. We all know what magic he created in that film. He was confident and focused on shaping his career. In 15 years, he’s composed for 75 films, branched into acting and created a space for himself there too. He’s in a good space now; his face allows him to even play a student. And, we don’t have too many people who fit that slot. Today, I’m directing him in Jail. And, he’s stayed the same over the years. I’ll credit his success to his enthusiasm. I wrote the film with three characters and I thought I would look at newcomers. But, I needed a saleable face. He came on board, and seeing his work, I will wager that this will be an important film for him. Post-production is on, and I can’t wait to see how people react to it.”

Jail is also a mid-budget film, the kind he works very well with. Was he never tempted to think big-budget considering he’s from the Shankar school of direction? “You need a different kind of ability to handle that kind of budget. It’s easier to find a producer when you have a reasonable budget, and some of us have not done well with big budgets. Over the years, Sir has pushed every envelope. Indian was big-budget at Rs 10 crore. He then showed us Anniyan, Sivaji, Endhiran, I…and now 2.0. Once a century, you see someone like him. Though our working styles and cinematic preferences are very different, I revere my guru the way as much as I do my father.”

Recommended

If there’s one thing about his career that Vasanthabalan would like to change, it would be the screenplays of Aravaan and Kaaviya Thalaivan. “The content was good; I will probably treat the films differently now!” There’s another angst hidden deep below. That, though he cast actors in unconventional roles and got them to deliver their career-best performances, his films did not provide them a dizzying rise to fame. “If people I introduced or cast differently had gone on to occupy the place that a Vijay Sethupathi, Suriya or Karthi do today, I would have been at peace personally and also happier professionally; I might have been able to make movies without too much gap between films. I feel bad that not many tapped into Pasupathy’s sensitivity, Bharath’s ability to emote or Angaadi Theru’s Mahesh’s realistic acting. If they had clicked, they would have been my legacy. For now, I’m delighted at the success Anjali and GV have achieved.”

*****

The Vasanthabalan interview is a Silverscreen exclusive.