பாளையம் பண்ணபுரம் சின்னதாயி பெத்த மயென்(மகன்) பிச்சமுத்து ஏறியே வாரான் டோய்…ஓரம் போ.

Make way for this cart;

Pay obeisance; lend a hand

To push it forward

For, here comes –

The son of Chinnathayee from Pannaipuram

On his all-conquering march

So goes the beginning of a song in the movie, Ponnu Oorukku Pudhusu, composed by an up and coming music director named Ilaiyaraaja. The year was 1979.

The State broadcaster, All India Radio, banned the song for vulgarity, yet the lyrics reveal nothing risque. Certainly, nowhere in the league of “Elandhapayam”, a song that not too long ago was carried across the airwaves.

Why then was the song banned?

*****

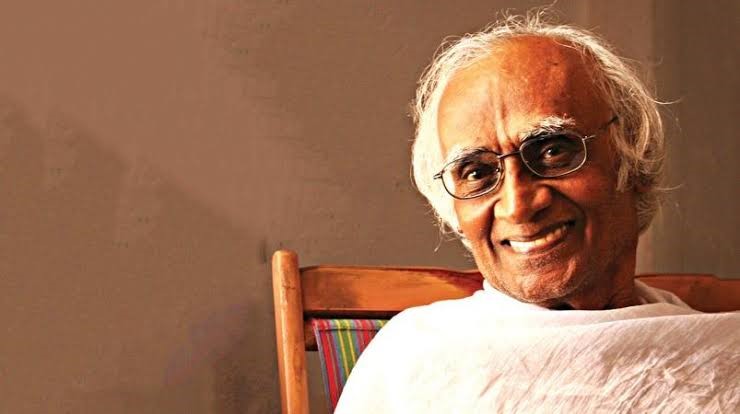

On Thursday January 25, music composer Ilaiyaraaja was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second highest civilian honour, by the Government of India. The 74-year-old, who has composed music for over 1,000 films in an illustrious career spanning over 40 years, was delighted by the recognition, calling it an “honour bestowed on all Tamils.” Reactions in Tamil Nadu were overwhelmingly positive, with politicians and celebrities congratulating the composer for what many felt was a long overdue honour.

However, The New Indian Express, a Chennai-based English daily struck a jarring note, describing the award as part of the BJP-led Central Government’s outreach to India’s Dalit community. The award, the newspaper said, is “important against the backdrop of Dalit movements in Gujarat led by Jignesh Mevani and the Bhima Koregaon uprising of Maharashtra.”

The story – done in poor taste – was widely condemned, with both celebrities and social media users criticizing the newspaper for suggesting that Ilaiyaraaja’s Dalit background had something to do with the timing of the award. Actor Kasthuri Shankar, in a widely shared Tweet, said: “Gods have no caste. Music has no walls.” The tweet was accompanied by a video – shot at an airport – of her spitting on the newspaper and dramatically ripping it in two, with a bemused bystander watching.

#Ilaiyaraja is a national treasure. God's have no caste. Music knows no walls. pic.twitter.com/9c2xFxDxXt

— Kasturi Shankar (@KasthuriShankar) January 26, 2018

Kasthuri’s reaction was typical of the refrain of many upper caste fans of the composer: He is beyond caste, and society has accepted him for his genius. That narrative is naive and false.

Because, Ilaiyaraaja is Dalit. And, there is no need to shy away from stating it. The elite, upper caste establishment tried every trick in the trade to diminish him. His rise is despite the establishment and prevailing mores, not because of them. Even though he has refrained from discussing his caste – drawing the ire of Dalit activists for brahminising himself – his caste and his identity are entirely relevant to his career.

*****

In the banned ‘Orampo‘ song, the lyrical references are unmistakable. Chinnathaayi was Ilaiyaraaja’s mother. Pannaipuram, his village. The song, written by Ilaiyaraaja’s brother Gangai Amaran, was a thinly-veiled message to their detractors in the Tamil film industry.

In the early seventies, when Ilaiyaraaja and his brothers came to Madras looking for an opportunity to make music in films, the Tamil film industry was a bastion of upper caste dominance. Even after Ilaiyaraaja got his big break through Panchu Arunachalam’s Annakili, he continued to meet with opposition from large sections of the industry. Manimaran, a writer who contributes regularly on Tamil Film Music, writes that “oram poyiduvaan” (He will soon be sidelined) was the phrase most commonly employed by those that opposed Ilaiyaraaja.

But barely three years after his first break, Ilaiyaraaja was the number one music composer in Tamil cinema. And the song was his message to detractors: Time For You To Give Way.

Tamil cinema and the media that appraised it were controlled by the elite upper class – inevitably upper caste, and more often than not, Brahmin.

A revolution was brewing, of which Ilaiyaraaja was a chief protagonist. However, victory was still years away for the revolution.

All India Radio, run by upper class administrators who saw it as their responsibility to be the gatekeepers of culture, took exception to the song because this was interpreted as a clarion call from the irreverent, low class, folk-music peddling upstarts from a remote southern village.

The ban led to a procession by Ilaiyaraaja supporters on Chennai’s Mount Road; and the controversies helped fuel the song’s popularity. The popularity was also fueled by a predominantly rural (and lower caste) vehicle: loudspeakers in tea shops across the state that played the song repeatedly, breaking AIR’s monopoly over the airwaves.

Another song that All India Radio banned for vulgarity was ‘Kettele Inge‘. Again, the lyrics reveal no ostensible vulgarity, but the song was set to a folk tune, and the lyrics were in Brahmin dialect; this was enough for the establishment to take exception.

*****

In the nineteen eighties, Ilaiyaraaja’s dominance in the Tamil film industry was absolute. He was the music industry. He scored for big banner films and big heroes, and was the face of several small and medium budget films; his output was prolific and high quality.

He was the most saleable star in Tamil films.

His commercial heft made him untouchable – just not in the sense that his ancestors were deemed to be by the Brahminical society of past.

Even Kailasam Balachander, “liberal” Brahmin and a doyen of the old order, who until then had resisted using Ilaiyaraaja in his movies, gave in, but it was an uneasy relationship that fractured very soon.

Balachander’s last film with Ilaiyaraaja was the 1989 release, Pudhu Pudhu Arthangal. The movie was released with, as it turns out, stock music for its background score. The director blamed Ilaiyaraaja’s supposed arrogance; the truth emerged years later. The year saw a strike by the film workers’ union in Tamil Nadu, and Balachander could not use Ilaiyaraaja’s dates because of the strike. When the strike ended, and Balachander wanted his movie released right away, the composer was in Mumbai for another recording.

Balachander took Raaja’s refusal to dishonour a prior commitment as an insult, and went on to incorporate stock music as background music, an act that drew the ire of the ultra-professional Raaja. The songs from the movie were super-hits, propelling an ordinary movie to box office success. The movie turned out to be Balachander’s last major commercial hit as a director. But the narrative had been planted: Ilaiyaraja was arrogant and difficult to work with.

Interpreting this spat as driven by personal animosity – there was plenty of it – misses the big picture. The number and identity of people who immediately banded together against the composer in this period belies any such benign interpretation. Ilaiyaraaja may have been the emperor of common men’s hearts, and reluctantly embraced by the upper caste film establishment due to his success, but his identity was always a source of derision for the establishment.

And, the establishment struck back when it saw a chance. While the choice of new composers by producers or directors can never be faulted, there was more to the rapid decline of big banner opportunities for Ilaiyaraaja than met the eye.

*****

Ilaiyaraaja’s struggles and his background are important to understand the context of his Padma Vibhushan.

His Dalit identity needs to be acknowledged, not papered over. The casteism and discrimination in the film industry mean that only an extraordinary, once-in-centuries talent like Ilaiyaraaja can make it to the top if he is from an unprivileged background. The resentment against the only other reasonably successful Dalit artist of recent times, Pa Ranjith, reiterates this. It is not easy to be Dalit, stay true to your roots and succeed in the industry.

*****

Another aspect of the resentment of his identity accepts Ilaiyaraaja, but rejects his more rooted music. This writer was once chided for listening to the ‘soodhra‘ (lower caste) music of ‘Solla Marandha Kadhai‘ by a cousin. The cousin was an unabashed Ilaiyaraaja fan, yet here he was, casually rejecting an album for its roots. The composer’s unabashed use of hitherto neglected folk instruments – such as the thaarai and thappattai, were also sources of derision for much of the establishment.

Ilaiyaraaja may have been accepted, but his background, even today, is anathema to a certain influential class of people.

Such is the environment in which Ilaiyaraaja operates still, and the one that young Dalit aspirants enter into.

Yes, Ilaiyaraaja is Dalit, and it’s entirely appropriate and important to state this fact in the context of his award. If you didn’t know it before, it is time to know and understand the disadvantages and hatred he faced due to it.

Recommended

Yes, Ilaiyaraaja is Dalit, and a genius. He cannot be a role model for aspirants – geniuses seldom are role models. The above average talent that emerges from similar backgrounds like his deserves a better environment than he faced. The route to that is not proclaiming that genius is casteless, but acknowledging that even he was accepted only after he embraced theism and his own brand of spiritualism.

Yes, Ilayaraaja is Dalit. His phenomenal career and immortal creations are all the more beautiful and rare, when you consider the innumerable disadvantages he continues to face because of his identity.

*****

The author can be found on Twitter at @nom_d_plum

Opinions expressed on Silverscreen.in are those of the contributor, and not those of the company or its employees.