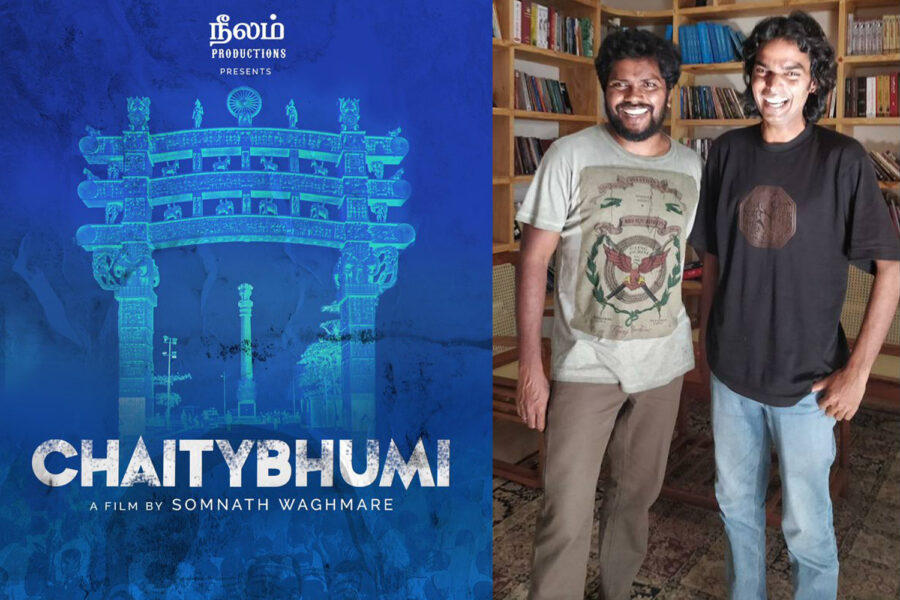

Filmmaker Somnath Waghmare is helming the upcoming documentary, Chaitybhumi, that revolves around the eponymous last resting place of BR Ambedkar, social reformer and icon for the marginalised. He says the irony of Chaitya Bhumi’s presence in Mumbai, the same city that is home to the Hindi film industry, which he feels lacks representation of the marginalised, is what prompted him to make the film.

The documentary is set to be presented by Pa Ranjith, the filmmaker who spearheaded a new wave in Tamil cinema by telling stories about the marginalised, especially the Dalits.

Waghmare, whose main interest lies in caste and culture politics of Maharashtra, sat down with Silverscreen India to talk about Chaitybhumi, caste representation in cinema, and Maharashtra’s pivotal presence in Bahujan movements. Previously, he has helmed the documentaries I Am Not A Witch, based on the persecution of tribal women in Maharashtra, and the widely-acclaimed The Battle of Bhima Koregaon: An Unending Journey, about the role of 500 Mahar Dalit soldiers of the East India Company in a battle against Peshwa rulers.

“I didn’t go in with the idea of making a full-length documentary [on Chaitya Bhumi], since the medium is costly. I had planned to just video document the place, out of my personal interest,” the filmmaker says. “In December 2019, I spoke to people and documented what is happening in Dadar around this place. As I watched the footage, I felt it was good and worth being made into a documentary. So, I started to speak to various concerned people, activists, historians, scholars to learn more.”

Every year, on the death anniversary of Ambedkar (December 6) called Mahaparinirvan Diwas, the social reformer’s followers throng Chaitya Bhumi. Waghmare says his documentary will show what happens in Dadar on December 6. “There are bookstalls put up, rallies are organised, skits and songs are performed.”

“There is a lot of debate happening in such places that are significant to Dalits. For many years, the Mumbai media has not acknowledged and has instead consciously ignored this event. But they do write about the crowd and traffic surrounding the place on such occasions,” Waghmare notes.

In Maharashtra, Deekshabhoomi (the place where Ambedkar embraced Buddhism), Bhima Koregaon, and Chaitya Bhumi are prominent places in the history of Dalits, the filmmaker explains. “Social gatherings are important in Dalit movements and songs and literature play vital roles in them,” he adds.

“I also met old people who witnessed the events of December 6, 1956, and this is part of the documentary too,” he tells us.

Waghmare found it interesting to note that Chaitya Bhumi exists in Mumbai, the same city that is home to the Hindi film industry. “The city also contains Ambedkar’s home, Dalit Panthers (an organisation to combat caste discrimination) is based here, and Ambedkar’s presence pervades the city and the state,” says the filmmaker, who is also pursuing his PhD on the topic of caste, culture, and power politics in Marathi cinema at Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai.

Calling filmmaking an art form for the privileged, in terms of both caste and class, Waghmare says, “The mainstream media and Bollywood always ignore Dalit lives. When they do portray them, it is only as victims, employing the Savarna saviour trope. They tend to continuously ignore the Dalit oppression in Maharashtra. I feel Bollywood is not blind, but tends to ignore with purpose. Even the recently released 83 has a dialogue against reservation policy. The structure of Bollywood is elitist in that way. Amid this, I want to tell the story of the Dalit community.”

Waghmare points out the contrast between Bollywood and the film industry in Tamil Nadu, where there is a support system for new filmmakers from all walks to grow and collaborate, like the one created by Ranjith.

Noting that, in the South, there has been a steady change in the filmmaking lens with more representation of the oppressed, Waghmare says he does not see such a movement happening in Marathi cinema or in Hindi. “This is why I approached Ranjith, rather than any Hindi or Marathi filmmakers. Power here rests with only a few, who do not want to talk about caste issues but only want to glorify their own culture. With advances in technology and the rise of social media, I hope this changes for good here too.”

Speaking about his association with Ranjith, Waghmare says he began following the Tamil filmmaker after watching the latter’s Madras (2014). While Waghmare was working as a contract employee at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, in 2016, he had attended the screenings of Pa Ranjith films that happened on campus. “I began to follow him and many people started to discuss him. He became quite famous in Maharashtra after Kabali. In 2018, I came down to Chennai for a film screening and found it was not difficult to access him.”

In addition to presenting the film, Ranjith will also be overseeing the post-production and release of Chaitybhumi.

Waghmare mentions that Chaityabhumi is multilingual. It contains interviews in Marathi, Tamil, English, and Kannada. However, it is primarily in Marathi with English subtitles, he adds.

The documentary is expected to run for about an hour. However, the editing process still on. The date and mode of release of the film have not yet been decided.

“This type of documentary is needed, not just for the marginalised but also for progressive people to understand the actual icons, history, and celebration of the oppressed. These types of films give hope,” says Waghmare.