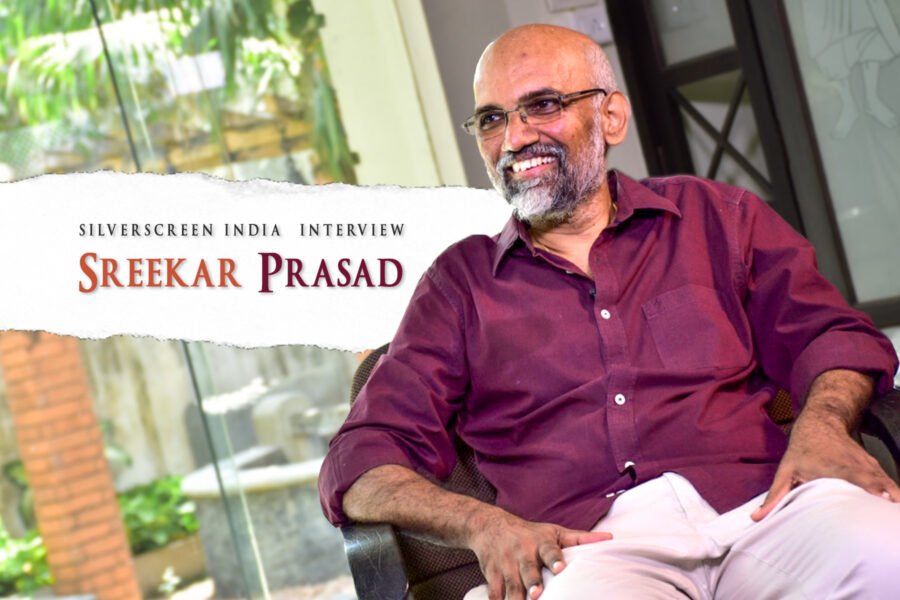

Editor Akkineni Sreekar Prasad, who has been awarded for his work in films like Kannathil Muthamittal (2002) and Okkadu (2003), has a filmography of over 600 films, that is still expanding. He is currently basking in the success of his latest feature, filmmaker SS Rajamouli’s RRR.

The film marks their first collaboration, Rajamouli having previously only worked with editor Kotagiri Venkateswara Rao.

“I received a sudden call from Rajamouli in 2018,” says Sreekar Prasad. “I had known him through industry connections and had been following his work, but we had not worked together earlier. It was also an unexpected call because he has a very close-knit team that he works with, like a family. However, he wanted to collaborate with somebody new and offered to briefly pitch the story.”

“Initially, I was a little nervous, because he was making a huge film. After the narration and further discussions, I could sense the world he was trying to create, something massive and larger-than-life. At the end of the day, I am also a film-goer and the excitement got to me when he narrated the story. Subsequently, in November 2018, we started to shoot.”

RRR is a fictional account of freedom fighters Alluri Sitaramaraju and Komaram Bheem, essayed by Ram Charan and Junior NTR, respectively. The period drama is set against the colonial-era and boasts a star cast drawn from several industries, including Hindi actors Alia Bhatt and Ajay Devgn, Irish actor Alison Doody, Shriya Saran, Ray Stevenson, and Olivia Morris.

A pan-Indian film made on a luxurious budget, it has gone on to become a huge financial success and a career-defining moment for the filmmaker and everyone involved in it.

RRR’s release was pushed several times owing to the ongoing pandemic before it finally released on March 25. “It is basically a theatre film. And fortunately, it came in a climate when it could get the big-screen release and at a time when people could come out to watch it,” says the editor.

Shortly after RRR‘s release, Sreekar sat down with Silverscreen India, to speak about the blockbuster, his first collaboration with Rajamouli, and his process when editing films.

This is your first association with Rajamouli. RRR has surpassed Baahubali, both in business and grandeur. How was it working as an editor on visuals of this scale and coordinating with the VFX team in parallel? Did you do any spot editing?

Rajamouli believes in giving the audience a grand experience; that’s his idea of filmmaking. He wanted to make everything spectacular and the whole unit worked towards making that happen.

Most of the scenes have realistic CGI and the team that handled it was very well-organised. They went through multiple revisions and rounds of approval before settling on the final version. I was not present during the shoot, but when it came to the edit table, at every stage, the CGI updates used to be communicated to the editing room. We could see the footage they were working on and all of them were pre-visualised with simulations.

What was the process you followed to edit RRR?

We had ample time to work on this project. When they were filming, I would receive the rushes (raw footage from a day’s shooting) in Chennai and edit them. As I did not visit the location, I could look at the film objectively, from an audience perspective, without letting the efforts employed at the shooting spot influence me. Between schedules, I travelled to Hyderabad, sat down with Rajamouli, and we finalised the sequences. Since the film is VFX-heavy, we had to give the team time to work. Once the edit was finalised, it was sent to the VFX team and they worked on the sequence. We followed that for all the schedules. There was also a lot of pre-planning, given the director really wanted to up his own game, in terms of the aesthetics, colours, and expressions.

The film is three hours and six minutes long. Given its big scale and rich visuals in almost every frame, could you tell us how you arrived at that runtime?

As per industry standards, a big-budget film is about two hours and 30-45 minutes, but here, keeping in mind that there are two big stars in their own right, we settled on a slightly longer runtime than a single star film. The editing was an ongoing process and we kept fine-tuning the film. At the same time, Rajamouli also took care to not overshoot. We had time to review it during the making and only what was needed was filmed. Further, owing to the cost and the big unit, every aspect was timed and executed carefully. When most of the first half was done, we were able to see it flow.

Which part of the film did you find hardest to edit?

There are about five to six major sequences in the film which were difficult. However, the introduction sequence of Ram Charan was particularly challenging. It is not a fight sequence constructed like the typical introduction scene of a hero and we had to add a sense of believability. The balance between him advancing and getting hit, being trapped in the crowd, making sure all the shots looked energetic, those were all quite challenging to edit.

Similarly, the pre-interval sequence was tricky as we had to imagine a lot of things that were not there. The storyboard told us animals were there and the length to maintain for the animals to jump down. It was a collaborative process between the editing and CGI teams. Rajamouli did a pre-visualisation of the shot and it was precise, thanks to which the edits and animation could be worked on.

The film’s beginning has three separate introduction cutscenes; one for the story and one each for the two leads, before the title card comes up. It seems like an unconventional choice. Can you speak about that?

It was a bit hard to crack it because we had to introduce these two forces and the story. Rajamouli had come up with the idea of titles (‘story’, ‘fire’, and ‘water’), to create a distinction and then merge the narratives. From the audience’s perspective, they would also expect separate introductions for the two characters. It could have followed from the ‘story’ segment to Bheem, but you would not have had a proper introduction for Alluri Seetharama Raju, who is perceived to be a British soldier. To establish all of these, we required proper introductions. The actual titles we came up with on the edit table, though the director had the characterisations with the fire-water symbolisms already set.

RRR boasts a huge star ensemble, but it’s the camaraderie between Bheem and Raju [who represent water and fire] that takes the forefront. Did you have a vision about how to balance the two actors’ onscreen presence?

The two characters were great freedom fighters, but their whereabouts in those 3-4 years of their lives is not clear in history and Rajamouli has given a fictional take on what could have happened if they had met. Both men had different outlooks, one was fighting for the tribal community and the other, for arms for people. Both ultimately succumbed to the British. With this as a backdrop, it is a story of two individuals, of an unusual friendship and conflict.

While writing the story itself, the characters were made equal. But, when we see the film, Bheem will have a little more prominence in the first half, because the other character’s past is not revealed. In the second half, Alluri Sitarama Raju is brought to the forefront. The unusual part of the script is that, within minutes of the film, they become friends and in the middle, they turn rivals, and the friendship is also uneasy.

You have edited films in a record 17 languages and have a vast filmography. At this juncture, what interests you? Do you have any wish list for the kind of movies you want to work on?

Anything in the mystery and thriller genres is most interesting for me as an editor and as an audience member. I like films like Talvar (2015), which I had worked on. There is a certain energy that is required to unravel a mystery slowly. I also like Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s films. They are serious and the story opens up as it goes, without any spoon-feeding, and they too leave you on the edge of your seat. That is the type of cinema I wish to work on. Also, the reason I have worked in many languages is that it opens your mind to different people, cultures, and ways of looking at films.

After all these years, do you feel like you have settled into a particular style of working?

Film critics may disagree, but I don’t have a particular style. As an editor, my job is to be like clay and blend with the vision of a particular director and film. Even if the director has shot 60-70% of what they had imagined, it will still require a huge effort to avoid things getting lost in translation. As I edit parallel to shooting, I don’t know what is going to come next. The advantage is that films get completed quicker. For example, with Vishal Bhardwaj’s Khufiya, within two days of my edit, he watched the edited version and the film is now almost completed. Once most of the parts are shot, they are assembled in a flow. Sometimes, the screenplay can change while editing too.

Your filmography includes both big and small-budget films. What is it like working on films made on different scales?

I was lucky in the initial stage of my career to get chances to work on serious films with different filmmakers. I always try to balance between them and big-budget films. I don’t take on too many big films continuously, because I don’t want to be stereotyped. Also, subconsciously, I use the teachings from smaller movies on big-budget films and vice versa. The inspiration of a Sivaranjiniyum Innum Sila Pengalum is what makes me try to get RRR as realistic as possible, subject to the constraints of its style. Similarly, I want a film like Sivaranjiniyum to be as smart as possible and break the preconception that an art film will be draggy. People are prepared to watch all sorts of cinema as long as it’s engaging, crisp, and emotional.

Lately, there is a trend of releasing deleted scenes from films post-release. What do you think about this trend?

It is all a matter of getting some buzz for the film in the week following the release. A filmmaker cannot include everything that was shot in the film and this is just a way to indulge the audience.

A word about your upcoming films?

Recommended

I am currently working on Ponniyin Selvan with Mani Ratnam. It is also a VFX-heavy film, made on a big budget. Mani Ratnam makes commercial cinema with his own brand of passion and sensibility. His characters behave realistically. In Malayalam, I have CBI 5: The Brain and also Bermuda by director TK Rajeev Kumar; the latter is releasing on May 6. There is Dasvi, which I have completed. Khufiya is in progress. Vishal’s son, Aasmaan Bhardwaj, is helming Kuttey, and I am part of that crew as well. Shabaash Mithu’s editing is completed and the post-production is going on. I also have Indian 2, but that is on hold for now as the principal people involved are busy.