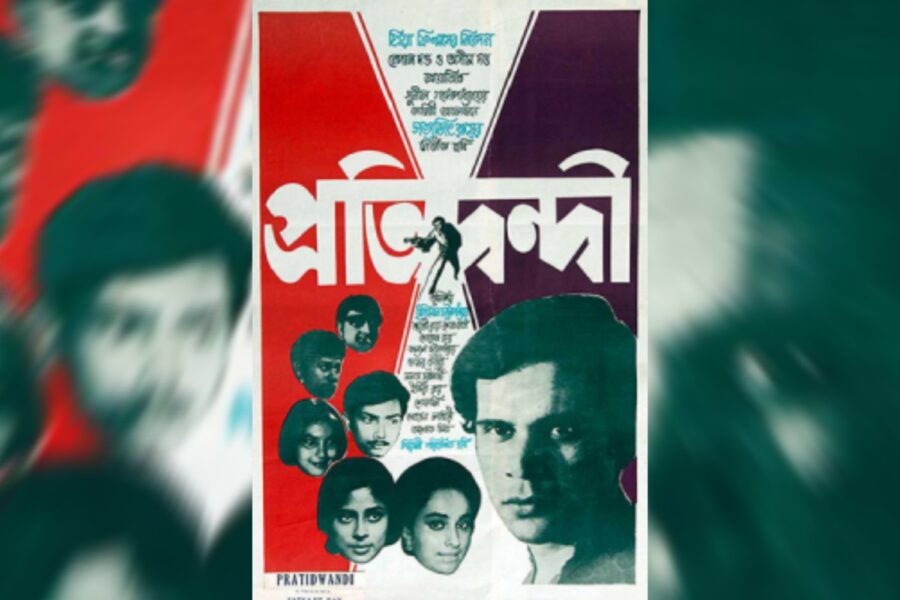

Satyajit Ray’s 1970 film Pratidwandi (The Adversary) was screened at the ongoing Cannes International Film Festival, on Thursday, and has been archived in the Cannes Classics Section. Cinematographer Sudeep Chatterjee, who supervised the film’s restoration, tells Silverscreen India about the process of restoration of films in India.

Pratidwandi is one of Ray’s many films that are currently being restored by the National Film Archive of India under the Indian Government’s National Film Heritage Mission, launched in 2016. Chatterjee was brought on board about two and a half months back, when NFAI was looking for a senior cinematographer to supervise the process.

“About two months back, I got a call from Mr Prakash Magdum, who used to be the director of the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), and he said that they have found these 10 negatives of the later works of Ray. For some films, they did not have the 100% percent negatives. They just had 60 to 70% of the negatives and the rest from the release prints,” says Chatterjee.

Chatterjee’s career of over two decades comprises a diverse slate of films, including, Dor, Iqbal, Dhoom 3, Chotushkone, Bajirao Mastani, Padmaavat, and the recent release Gangubai Kathiawadi.

The National Award-winning cinematographer said that he was happy, when he was contacted to head the restoration “because in the wrong hands it can be something else.” His entire intention was to make sure that the future generation can see them for their authenticity, just like he did.

“I have seen these films in my childhood, in theatres. I saw them in their full glory, and I saw what it did to me. It is very unfortunate that a few years back, when I would try to show these films to my children, they would refuse to watch it because of the inferior quality. A lot of Ray’s written works like Hirak Rajar Deshe and Sonar Kella, and later works like Ghare Baire and Agantuk, they are in really bad shape as far as the digital versions are concerned,” Chatterjee adds.

Pratidwandi is the first part in Ray’s Calcutta trilogy, and follows the story of Siddharta, an educated middle-class man, caught up in social unrest due to rampant corruption and unemployment. Siddharta cannot align himself with either his revolutionary activist brother or his career-oriented sister. The film features actors Dhritiman Chatterjee, Debraj Ray, Krishna Bose, Indira Devi, Kalyan Chowdhury, Joysree Roy, and Sefali.

The film, Chatterjee says, was recovered from a reluctant Purnima Dutta of Purnima Pictures, the production house that had backed Pratidwandi.

“When the academy (NFAI) had come asking for the films, she said that she didn’t have the negatives. Because she didn’t want to give it to the academy. For so many years she had it, and no one knew. Then Prakash Magdum met her and convinced her to give the negatives,” mentions Chatterjee.

However, the entirety of the film could not be used from the negatives that were recovered from Dutta.

“Only about 70% could be used. The rest was very badly damaged. When we were trying to take the negatives out, parts of them were falling off. So, about 70% of the negatives we could manage. The rest were taken in bits and pieces, from the three release prints,” he adds.

Chatterjee explained that the process of restoration follows two levels.

Restoration entails acquiring the available film negatives, scanning them, and cleaning them to get rid of any scratches or dirt. Conducted manually, it has to be done frame by frame, and one needs to take care that the original frame structure is not altered.

He notes,”Once that happens, it comes to me to form the digital scan through grading, to take out release copy for DVDs, Blu-Ray, and for streaming as well as theatrical projection.” He adds that he is supervising the restoration drive of Ray’s films, but from the point-of-view of a Director of Photography.

Restoration in India

Chatterjee notes that the aspect of acquisition is tricky. He explains that the traditional method of storing films, followed producers submitting the film reels to labs after their releases in cinemas. These labs came with vaults that controlled humidity and air conditioning, among other factors, that were conducive to the storage of films.

While some producers submitted their films with the NFAI, others chose the labs.

Around 2012, or 2013, when there was a shift from shooting on film to digital cameras, these labs went out of business.

“So, most of the labs shut down. When they shut down, they sold all the equipment on junk basis. They tried to contact a lot of producers to come and collect the film negatives from them. Some producers took it seriously, while others didn’t. Some producers are not even there anymore, and the next generation did not keep a tab on it. So, a lot of these negatives were just thrown off in the junkyard. A lot of negatives were recovered from junkyards and scrapyards and old second-hand shops,” he said.

Lack of proper technology, and not intent, was another deterrant factor in the restoration of Indian cinema.

Chatterjee explains that even a decade or two ago, when films were digitised, the digital technology was not very evolved. “There were no digital cameras. Just normal tele-cine machines, which are not the best way to get all the information that is there on the film,” he adds.

He notes, “What happens is, when the film is kept for such a long time, the moment you try to take it out, unwind it and put it through a scanner, there are chances of the film breaking, or getting stuck because of the moisture. Today, we have the facilities and the technology to make sure that that does not happen.”

Recommended

Chatterjee remarks that the NFAI has set up a whole facility where they scan the negatives and the release prints on 4k, and that the facility is “top-notch.”

While the NFAI has been able to restore Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe, Agantuk, and Shatranj Ke Khiladi, aside from Pratidwandi, there are several films that continue to be missing.

“We have lost a lot of things. For instance, the negatives of Kanchenjunga is not even available. We could not find the negative even for Hirak Rajar Deshe, but what we did was that we restored it from a master positive. When you are doing restoration work, you amass all of the things available, and take from the best only,” he mentions.

“They must be lying around somewhere. It’s just about time,” Chatterjee concludes.