Ms. En Scene – where Ranjani Krishnakumar concedes that cinema is life. Opinions expressed are those of the contributor, and not those of the company or its employees.

As a kuppai padam addict, this month’s edition of this column is an existential crisis for me. I watched two kinds of ‘mass’ films — one I absolutely loved because mass, and another whose mass elements I hated. And this is killing me.

So, what is mass?

Take the introduction of Vijay in Sarkar (2018). Everyone is excited for the visit of Sundar Ramaswamy, the character he’s playing. IT companies are scared shitless. Media is frenzied. “Avan monster, Genghis Khan, such a playboy, but he’s cool,” says a woman with flirtatious admiration, after Googling him. We break into a song in Las Vegas, the location is helpfully displayed on the screen. Silhouette… point-of-view shots… low-angle shots… close-ups blowing smoke.

Cut cut cut. That’s it! Mass is exactly that — blowing smoke up a hero’s ass (and his fans’). It is the process of exaggerating a character’s prowess, even before he appears on screen, relying solely on the bottomless bullshit-swallower that is Tamil cinema fandom. Instead of showing why and how each of them became invincible, and building some kind of internal logic, they just give him mass. Among other things, this mass presents itself through fights where the hero single-handedly beats up tens of henchmen.

Wikipedia tells me that mass determines one’s strength and attraction. QED.

*****

In and of itself, I don’t have a problem with mass.

It makes for a certain genre of film, which serves a specific purpose. It gives the “fantastical escapism you crave after working your dreary job, or jobs, all week, or suffering from needing a job and not having one…” writes Eileen Jones, in her essay about why so many of us dig the John Wick movies, which are all about violence and killing. I’d say, we dig our mass films for the same reason: They allow us to live vicariously through the righteous invincible hero.

It has its place. Because as audience, when we buy tickets for a mass film, we know what we’re walking in to. Expecting (a decent and equitable) narrative in mass film is like expecting (a feminist) story in porn. Some of us most certainly want it, but most of us are in it for the climax. I don’t need to be told Rajinikanth is going to rise victorious. You wouldn’t dare make a film any other way, ask Mani Ratnam. Just show me some fireworks and I’ll be on my way.

*****

But today, every film and every male upstart wants mass.

Take the Ratchagan Nagarjuna-level build up for Atharvaa, who plays a low-ranking cop in 100 (2019) — a film that had all the makings of a decent thriller, let down only by its compulsion to be mass. Far from being a genre on its own, today, mass is an epidemic that every film seems to have caught. So much so that they don’t even know how to write hero introduction without blowing smoke.

And its reason: The hero. Tamil cinema is a hero-driven industry, and every Arun Vijay, Atharvaa, and Vijay Antony wants to be the next Rajinikanth. Why else would moderately funny Sivakarthikeyan want to play a shrew-taming misogynist in a cesspool of a film such as Mr. Local (2019)? Or a somewhat talented Simbu want to spout alliterating garbage in an already hyped up film such as Vandha Raajavathaan Varuven (2019)? Why else would the hugely talented and successful Vijay Sethupathi return to mass after each adventurous cinematic outing?

Because in the world of Tamil cinema, mass is the gold standard, and the true announcement that you’ve arrived. If you’ve already arrived, it’s the fuel that keeps the engine running.

Which is why, a film about the sexual assault of three women and its aftermath spends so much screen time on mass. Why bipolar and manic episodes become some kind of superpower. And why a psychiatrist warns the henchmen against fighting the mass hero, instead of rushing medical help to a patient in need.

Without mass, the Tamil hero feels emasculated.

*****

But what about the woman who plays the hero?

Ever since her return from the marriage-induced hiatus, film after film, Jyotika is rising as a hero in her own right. Her journey is parallel to most mass heroes of today. She played the underdog seeking inclusion in the 2015 film 36 Vayathinile, which was character-driven and realistic. She played the strong-from-the-start, yet person-next-door in Magalir Mattum (2017) and Kaatrin Mozhi (2018), to moderate success and acclaim. Like everyone from Vikram to Vishal, there was a Bala film, Naachiyaar (2018) with his very own brand of mass — abusive language and gory murder intact. This film also turned out to be her cop-film — another signal that one has truly arrived in the Tamil film industry.

This year’s Raatchasi took her mass appeal to a whole new level. She had slow motion smoke blowing, low-angle shots, other characters building her up — a Singh talking about her past in the military, no less! In the film, she went beyond telling women ‘go girl’ and gave generic social message, like in Murugadoss films.

More surprisingly, she had a dramatic fight scene — her punching hand shown in close up, as she flicks rice off it. A woman getting a fight scene choreographed with real aggression in the post-Vijayshanti era: If that’s not marana mass (for female hero standards), I don’t know what is.

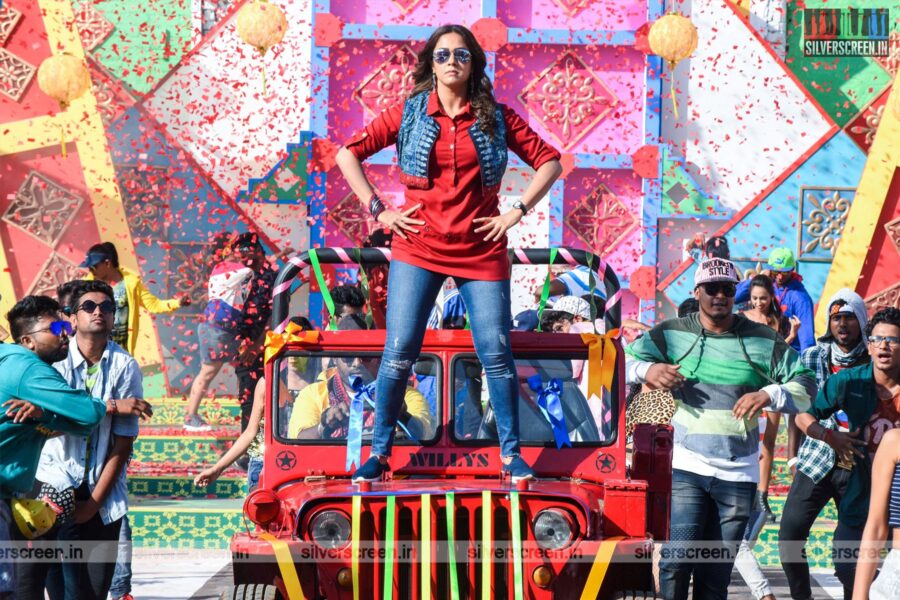

Oh wait, I do. Jackpot (2019)! Jyotika, as conwoman Akshaya, gets better, longer, harder, funnier fight scenes than Geetha Rani did in Raatchasi. Not just that. Counting all the slow-motion walk, wider range in wardrobe, snake stunt, social message and changing the future of Tamil Nadu — she gets significant vetti build up. “Akshaya paathukkuva” [Akshaya will take care] is said pretty often. Revathy, her sidekick — SHE HAS A SIDEKICK, YOU ALL! — even makes a smug face doing so.

Recommended

So, as the climax was nearing, in that dark forest, fighting tens of goons, I found myself thinking, Jyotika-mass, for me, is a dream come true. It is the fantastical escapism I crave, with Jyotika being the live-action Buttercup from Powerpuff girls. I would happily pay to watch Jyotika do mass, not only because women need mass heroes too, but also because it’s perhaps the only way to command mainstream (read: male bastion) legitimacy, and Jyotika could surely use that. So, go on, continue blowing smoke up our asses.

Ajith, on the other hand, could truly have put an end to this epidemic called mass, and he failed. In the least, he could have shown how it is done. He had the opportunity to show that author-backed roles without the compulsion of ‘one fight, one song, and never-ending build up’ have a place in mainstream Tamil cinema.

And, he bungled it.

*****

Unmistakable. Meticulous. Predominantly an essayist. Evolved from a marketer. Ranjani Krishnakumar eats Tamil films all day and fruits for breakfast. Roosts with pair in Chennai apartment. Usually found chasing Vitamin-D. Believes “Dei” or “Pch” is the answer to all questions.

Twitter: @_tharkuri