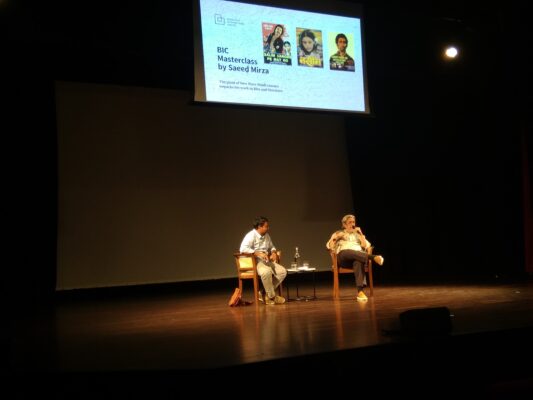

“Don’t try to be good, try to understand”, filmmaker Saeed Akhtar Mirza says, reflecting on a hideous story idea proposed by two well-meaning acquaintances of his. To understand: that might be the verb Mirza most used at the masterclass organised by the Bangalore International Centre in February.

In conversations with different hosts, Mirza talked about his childhood, his turn to filmmaking, the blossoming of his political awareness and various aspects of his filmmaking and writing practice, including the circumstances of production of the three films screened at the event. Together, the films and the conversations evoke the image of an artist for whom practice is an extension of one’s intellectual relation to the world, a transcription of one’s ‘understanding’ of it.

As the child of noted screenwriter Akhtar Mirza (Naya Daur, Waqt), Mirza found cinema and cinema-related discussions an integral part of growing up. But it wasn’t until his 14th birthday, when his father projected a copy of the Soviet film Battleship Potemkin, that the medium took firm root in his consciousness. The image construction, he says, was shocking. He’d subsequently have one classic of world cinema screened at home every month. The realisation that cinema could accommodate ideas, conversations, polemics as well as narratives enthralled him.

IMG_20200221_211022

Adult life, however, had different plans, and Mirza found himself working in an advertising firm. He experienced an internal crisis eight years into the job. Encouraged by his wife, he applied for a course at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), coming back to the road he had left behind in his adolescence.

At the institute, then under the direction of Girish Karnad, Mirza set out to document protests against slum evictions in Bombay. The sheer imbalance in clearing thousands of residents to make way for a few hundred government officials struck him, instilling an abiding desire to speak to people and hear what they have to say. Emergency was declared shortly after he finished editing the documentary, simply titled Slum Eviction.

How is it that a cosmopolitan— “internationalist”, in Mirza’s description —unmarked Muslim from west Bombay became a committed, politicised filmmaker producing work attuned to realities that had little bearing on his social situation? Mirza traces the transformation to an incident from childhood. At the age of ten, he refused to enter the Bandra mosque with his father to offer prayers on the day of Eid. He didn’t believe in god anymore, he told his father, who asked him to remain seated at the steps outside the mosque. This original doubt paved way for others, taking him on a journey of progressive ‘declassification’ of the mind.

Mirza relates this opening up of the mind to diverse ideas, especially at the film institute, to the predicament of the protagonist in Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastaan (1978). One of the two films produced by the quasi-legendary Yukt Film Cooperative Society (the other being Mani Kaul and K. Hariharan’s Ghashiram Kotwal (1976), in which Mirza also worked).

Arvind Desai, says Mirza, is about being young and hailing from a particular social milieu. He adds that Arvind’s predicament, of rationalising the gap between acquired ideas and lived experience, of harmonising the two, was his own. “Our school education is status quo-ist”, notes Mirza, “we need outside ideas to shake it up”. Arvind Desai thus became this “journey of guilt”, tracing the chasm between received education and political action.

His subsequent film, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai (1980), set around mill strikes in Bombay, is the story of the politicisation of a bourgeois businessman. It came at the end of a significant personal change, says Mirza, the result of “being swept into a vortex of ideas. It was an age of questioning at a mass level,” he adds, referring to the international protests against the Vietnam war in the seventies. And Albert Pinto was another step towards engaging with the other, in this case with one of the largest organised workforces in the country.

Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho! (1984) adopts a sophisticated expositional framework that combines the tamasha form of theatre, a middle-class melodrama and a documentary. Even though the decrepit chawl we see in the film seems like a real slice of Mumbai, the film itself has only tenuous links to realism, weaves as it does in and out of a burlesque mode of narration. Bhisham Sahni’s dignified face, representing for Mirza ‘civility in an uncivilised world’, is pitted against the machinations of a caricatural Naseeruddin Shah, whose career rises just as the chawl continues to crumble.

On being asked about the long, revealing titles of his films, Mirza speaks of a democratic dialogue with the audience, of not wanting to deceive them. When the viewer buys a ticket, he says, he has an idea of the film he’s walking into. “It’s not some Khandaan or Jurm.”

In no other film is the title as illuminating as in Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989). The instruction—don’t cry over Salim the cripple—positions the film as a tragedy, with the fate of its lead character sealed from the start. Salim, a low-level hustler with dreams of making it big as a gangster, gets a rude awakening when he’s showed his place by a system that views him differently. The Mumbai slang of Salim and those who abuse him are far from the Byron-quoting urbanity of Mirza, who had to undertake midnight trips to Dharavi to talk to real underworld figures as part of his preparation.

Mirza describes the last of his five major films, Naseem (1995), as the final nail on the coffin of the idea of India. Set in the months preceding the destruction of the Babri mosque, Naseem paints an elegiac portrait of a syncretic, tolerant nation, thrown into disarray by the events of and after December 1992. Like Salim, but on a lower, more heart-breaking key, the teenager Naseem (Mayuri Kango) is forced to confront her social identity as reflected in reaction of those around her. Naseem finds Mirza articulating space with greater surety, with the fluid camera stitching the rooms of Naseem’s middle-class household into long, unbroken shots.

Responding to why he didn’t direct films at the same clip after 1995, Mirza said that he felt he didn’t have anything more to say, that he needed to gather himself. Over the next few months, he travelled extensively through the country, meeting people of all stripes from across geographical regions, in order to “regain his faith in people”. “The Babri demolition”, he adds, “was an assault on what my mother stood for”. And this journey across the Indian heartland was necessary to restore his belief in the basic generosity and benevolence of ordinary Indians.

Mirza’s energy and effort after Naseem were directed towards writing: screenplay for a children’s film Choo Lenge Akash (2001), but also two books. In a conversation with Aakar Patel on his writing output, Mirza detailed the idea behind his first book, Ammi: Letter to a Democratic Mother (2008). Letter, he says, is a tribute to his mother as an individual, but also a remembrance of history, an act of unburdening. His mother’s deep thirst for information was often checked by an insecurity about herself in face of an erudite husband and English-speaking children. With conversations unfolding at home in English, reflects Mirza, language became a tool of distancing. Letter was a way to address this distance, to recognise the silent revolutionary gestures of his mother—a document, then, at once personal and political.

“It’s unforgivable if you’re over 50 and don’t have a sense of our history”, asserts Mirza, pointing to the collective amnesia the country has developed around the Babri demolition. Just after the events, in a workshop with students of direction of the batch of 1992 at FTII, he admittedly asked students to mull over three questions: whether India was (a) more intolerant (b) more violent and (c) more religious than any other country in the world. When the students came to the conclusion that India was no special case, he counselled the students then to cut out the clichés and understand the causes and effects of historical upheavals.

Recommended

Cause and effect. Words crucial to both the inner workings of Mirza’s films and his view of history. Marxist in spirit, Mirza’s work never settles for easy simplifications of human behaviour, even when framed as melodramas, as Mohan Joshi or Salim are. It’s also a Marxist term he coins to characterise the changes the nation has been subjected to in the past thirty years; a “lumpenisation of aesthetics” has taken place, he says, and the globalisation of the economy has but resulted in a “ghettoisation of the mind”.

“Each film I’ve done is a journey of understanding myself and the world,” reflects Mirza. His work invites us to undertake the same journey, to leave the self-imposed ghettos of our mind.

Featured image: Scroll.in