Pikchar With Rita is a fortnightly column on cinema by Rita Kothari. She’s a Professor of English at Ashoka University. She does not “do” film studies.

***

Relationships are hard work. Hindi cinema does not tell us that. It stops before we get to that point. The topsy-turvy, part funny, part melodramatic ride comes to both the end and marriage. So we don’t get to see what happens after in the sphere of the banal everydayness. It is the domestic in which some of the less dramatic, but recurring tests of relationships lie and domesticity is almost entirely missing from films.

Before you rush to cite the number of “homes” to me, let me ask if you are able to think of too many films that are about quibbles over which vegetable to cook; or who picks up the grocery; or cleans and washes, or the pinpricks of the joint family, or the repetitive nature of arguments and love-making?

Or how prejudices new and old cleave to the surfaces, like the grime on kitchen shelves. Domesticity does not make for spectacle, nor is it a life-and-death situation over which histrionics need be wasted. Hence the couple in cinema is the couple before marriage; but a set of parents after marriage, and life is not about them, but the one they have procreated.

The child is rarely the child caught in the family politics, but grows immediately as a young man or woman and falls in love with someone s/he is not supposed to. Conjugality without procreation is rare. Meanwhile, the world view behind marriage –as-a-culmination requiring no more to be told is to also to bypass the social history of everyday life in cinema.

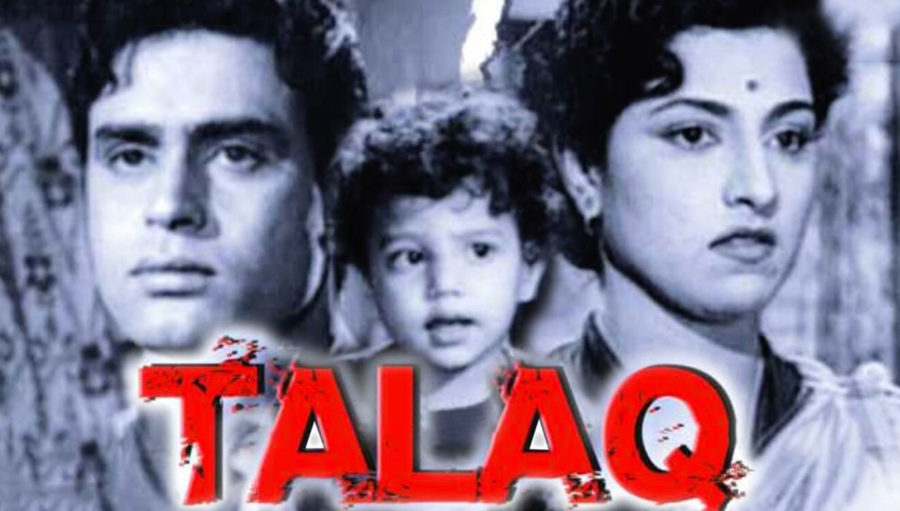

For all my sins, I had to watch a scarcely known (for good reasons) film called Talaq. Made in 1958, with Rajendra Kumar and Kamini Kadam, the film is the second response (in addition to Mr. and Mrs. 55) known to me about the Hindu Code Bill that established both marriage and divorce through individual choice and agency.

The relationship between the couple in Talaq is ‘ruined’ by the meddling father-in-law, and the wife’s refusal to be ‘aurat’ and mother in true sense of the word. The family breaks down, only to be recuperated in the name of the little child who needs both parents. The father is made to realise his mistake and all is well with the child, and by consequence with Jack and Jill, or Ramesh and Sheela, if you will.

The estrangement between a husband and wife with reasons that do not get externalised – pesky mother, a villain, a catastrophe – are hard to see. I wonder if estrangement and alienation in Indian society is more threatening than death; for death does not disturb the moral universe, such as the sanctimonious edifice of the family upon which the Indian society stands.

Unlike Talaq, Mr. and Mrs. 55 does not get to a real marriage; an act both physical and metaphorical, but makes the westernised divorce-seeking wife learn the value of the family. The film mocks at short-sighted “feminists” (represented in the film by Lalita Pawar) who ruin such Indian values. The decade of the fifties took both the nation and romance in its fold as simultaneous and mutually supportive institutions.

Recommended

However, a gentle and somewhat poignant film (appearing twenty years later) that has the domestic sphere with little burden of nation and culture is Kora Kagaz. Played by Vijay Anand and Jaya Bhaduri (then) the couple in this film finds itself caught in some individual errors of judgment; and perceptions of class difference that mediate their conjugality.

There’s much laid to waste between two sensible and loving individuals, otherwise unfettered by shallow needs and expressions. Conjugality is ruined in South Asia as much by inaction as actions of the relatives. To be able to think clearly through the disruptive and clamorous sociality is a difficult proposition, especially since it requires walking a tight rope between different needs. The song “mera jeevan kora kagaz” by Kishore Kumar haunts the film, laying bare, like an empty page, loneliness not only of the individual, but also of a pair that cannot make togetherness out of the solitude of two people in an Indian marriage.