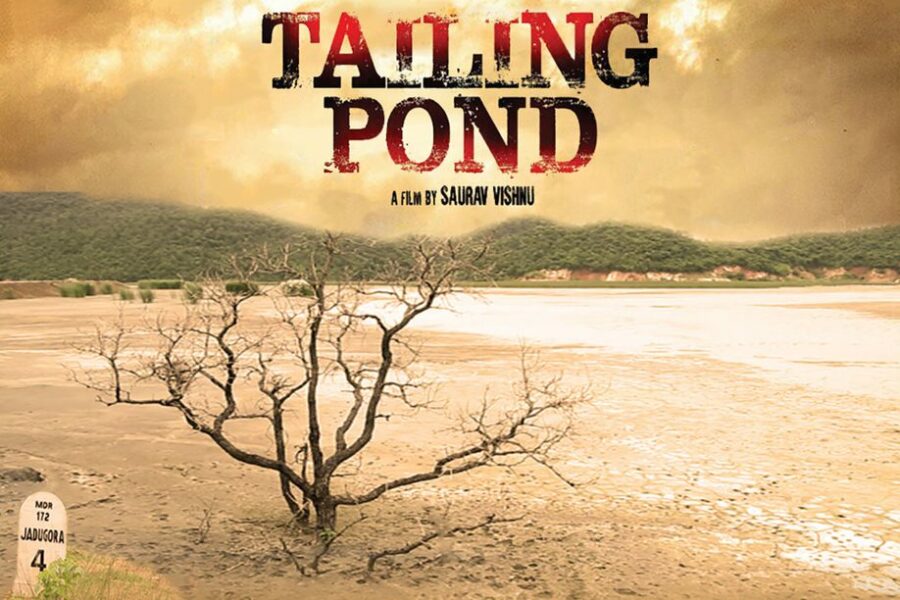

Tailing Pond begins with a panicking man who runs across the jungle barefoot to get a doctor to attend to his wife in labour. The doctor informs the father that their child is born without limbs. It is the only scripted scene in Saurav Vishnu’s documentary on the effects of uranium contamination in a village in Jharkhand, India.

The film follows tribal families in the small town of Jadugora and their afflictions as a result of the contamination caused by the tailing ponds that their houses are nestled around. A tailing pond is “a facility designed to receive and store tailings, or the refuse material resulting from the concentration of minerals.”

The documentary is narrated by actor Cynthia Nixon, renowned for playing Miranda in the Sex and the City franchise and last seen in the HBO Max spin-off And Just Like That.

Director Saurav Vishnu confirms to Silverscreen India that Nixon will also lend her voice when Tailing Pond is expanded into a six-part documentary series. And next time, he plans on casting an Indian voice alongside Nixon’s. “I feel that if we have two voices telling the same story from different perspectives, it will resonate with the global audience.”

The conception of Tailing Pond

Vishnu was first made acquainted with the subject of tailing ponds, and the issues surrounding them, by his father who was a cop.

“My father was an inspector of police and he was once posted at Jadugora. When I was looking for a subject to do my first film, he was the one who introduced me to the issues there. He saw a lot of things that he felt were out of line. He witnessed the sufferings of the people but, posted as a government official, he could not help them out directly. When he introduced me to this story, I started my own research,” the filmmaker says.

Vishnu divided his next six months between researching and visiting Jadugora. It was only after this that he knew he wanted to make a film on the issue of uranium contamination.

Tailing ponds and their impact

“One tailing pond is the size of ten football fields,” Vishnu explains. “And the villagers are nestled around these ponds. Now, it’s not like they settled there after the tailing pond was made. In fact, the tailing pond is made on their land – land which was acquired by the Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL). It is a government entity and one would therefore expect it to act more responsibly than a private one.”

However, this has not been the case.

The UCIL constructed the uranium mines in the town of Jadugora, 20 kilometres from Jamshedpur, after Independence and mining began in 1967. The tailing ponds are just over a hill, across 193 acres of land that contain mildly radioactive, unguarded waste.

As shown in the documentary, while the UCIL has erected a warning sign, the consequences on the tribal people have been dire. 47% of women in Jadugora have reported miscarriages, disruptions in menstrual cycles, and other fertility issues. Further, 51% of the children are afflicted with limb deformities and skeletal distortions, right at birth.

According to a Quint report, cancer as a cause of death is more common in villages surrounding uranium operations.

While tailing ponds can be water bodies, the one in the documentary is a dry patch of land with cracks, and yellow-coloured stacked tailings. The situation worsens during the monsoons, when the refuse seeps into the groundwater and into the nearby lakes and ponds – the only sources of water for the people of Jadugora.

The UCIL’s annual report for the session 2019-20 recorded a net income of Rs 2,420 crores, which included investments in healthcare, ecology, and environmental protection. Contrary to the company’s claims, the documentary shows the abysmal healthcare situation in Jadugora, with the only medical centre remaining shut for most part of the year. This hinders the villagers – largely informal labourers – from accessing medical care. Local homeopathic treatment becomes their only alternative, but proves to be futile in cases of serious ailments.

Moreover, the disability of the children, and their consequent dependence on their parents, deters the women’s chances of employment.

Obstacles faced during the production of Tailing Pond

The documentary, which went into production in 2015, took four years of “back-and-forth filming,” as Vishnu puts it, owing to his lack of formal education in filmmaking.

“I was struggling to edit my film because I didn’t know how to do it. Our first cut was over 80 minutes long and then we went through seven more cuts before we finalised the film as a short that would make up the first part of the story,” he says.

Casting was another challenge since he was his own casting director, and it took him a year to cast characters who only appear for 2-3 minutes in the film. They are all tribal actors, he tells us.

The casting of the narrator proved to be a big challenge as well. Nixon was not the director’s first choice. He approached her because he was “delayed by [his] own people for such a long time.” His original plan was to use an Indian voice.

Late actor Irrfan Khan was the first celebrity that Vishnu had approached. However, just as Khan had almost agreed to lend his voice to the cause, Vishnu was informed of his ill health. Khan died of a colon infection in April 2020.

Vishnu then approached actor Sonam Kapoor, who was also unable to commit to the project. “I think she got scared; perhaps she did not want to be criticised for her involvement in such a sensitive issue,” the filmmaker says.

He finally chose Nixon after a quest of 14 months. “I wanted to get an Indian voice, but I failed. When I failed, I had to use other means to keep the project going. I had to hire somebody from outside, but it had to be someone who was honest.”

The team also had to keep the project under wraps for as long as possible, since it involved government-owned uranium mines and they did not want to be projected as enemies of the State.

While Vishnu and his team did not face any tangible resistance, his father was contacted by a possible intelligence bureau in 2015. “When I heard that, I realised that I was on the right track,” he says.

The filmmaker adds that he also felt a constant pressure during his interaction with the locals and could sense their fear. “I made sure to not create more problems for them by trying to gain any media attention for my film when I was shooting. Because they have to continue living there; I don’t. I kept working on my film quietly. We only wanted to put out the word when we had something concrete.”

Vishnu adds that his efforts to highlight the plight of the locals have often been misunderstood as a voice against uranium extraction and mining. “I completely support uranium energy and uranium mining. And I am not associated with anyone who is against it, though I was approached by a lot of people. I stand for true humanitarian issues.”

What next?

There are nine tailing ponds in Jadugora, Vishnu tells us. “I’ve showed only one. Plus, the UCIL has acquired new pieces of land to construct new tailing ponds.”

Recommended

“I am going to continue making films on Jadugora till the people of Jadugora are in safe hands,” he asserts.

There haven’t been any tangible changes on the ground, the filmmaker says. “If there had been any, the news would have reached me. I feel bad to even ask them what’s happening because I know nothing is happening. And until I hear from them, I won’t stop.”

The right way to approach the issue, according to Vishnu, would be to first acknowledge it. “Secondly, they need to be relocated. All the people who live by the tailing ponds, live on their own land. They were promised jobs. The only jobs they received force them to go as deep as 100 feet into the uranium mines with no protective gear but their lungis. And they are bare feet.”

Only once the objective of proper relocation – and not simply a cheap housing alternative – is achieved, will other demands be put forward, he adds.

The film has, meanwhile, travelled across the world. Tailing Pond has been screened at various film festivals, including the New York Indian Film Festival and the Jaipur International Film Festival. It was also in the run for the Oscars.

Now that both the film as well as the issue have received attention, both nationally and internationally, Vishnu hopes that Indian celebrities and public figures will no longer be reluctant to associate themselves with the cause.

The upcoming films, he notes, will delve deeper into the consequences of uranium contamination. They will also follow the documentary format, since it helps him “represent things in a realistic way.”

As he puts it, “I don’t want to show what I want to show. I want to show what’s happening.”

The objective, at the end of the day, as promised to the people of Jadugora, is to “put their story, and our state Jharkhand, on the world map. And that’s what I am looking to achieve.”