Filmmaker-activist Divya Bharathi of the CPI (M-L), who was forced to leave Tamil Nadu earlier this month following rigid opposition to her film Kakkoos, continues to take her film across the country.

A scene in Divya’s documentary – Kakkoos (Toilet) – shows a sanitation worker in Madurai enter a government-built public toilet along the road. It’s Deepavali, and as celebratory bursts of fireworks echo in the background, the worker, stooped with age, walks barefoot inside a toilet stall piled with human excrement. He has one of those brooms fashioned from dried stems of coconut leaves – commonly used in southern India – the only tool with which he clears faeces and unclogs the drain. Neither does he wear footwear, nor is there any protective gear on his person. His face betrays nothing, until he sees someone using the adjacent stall, which hasn’t been cleaned yet. Then, the worker yells in Tamil. “Can’t you wait for five minutes?”

His work for the day is far from done. A corner of the pink-tiled bathroom floor is slimy with something that suspiciously looks like sick. The worker scoops it up with bare hands, bins it in one of those huge dumpsters.

“You’d see visuals of public toilets from a lot of places in Tamil Nadu,” says Divya Bharathi, who filmed Kakkoos for over a year and a half across cities in the state, “But the Chennai toilet we have shown has no closets. It’s just a floor on which everyone defecates; meant to be cleaned by the sanitation workers.” Divya talks to me from a train; she’s on the way to Mysuru for a screening, having earlier shown the documentary at National Law School and IIJNM in Bengaluru, and a few places in Kerala.

The year has been quite an eventful one for the filmmaker – she was arrested in the last week of July, in connection with a case registered against her in 2009. While Divya was let off on conditional bail, the sudden revival of the case, and the order to arrest her for failing to attend a court hearing about a 2009 student protest that she was a part of, raised several questions. And the most pertinent of all, involved her recently released documentary, Kakkoos, which tears into the government for still upholding the tenets of caste slavery with respect to manual scavenging. That’s not what triggered her arrest though. Exactly a week before the police had come calling at her house in Madurai, Divya had posted a video on her Facebook page. It featured sanitation workers speaking out against the treatment meted out to them by the dean of Anna University, Dindigul, Chitra Selvi. The News Minute reported that around 15 workers were employed on campus, for a monthly salary of Rs 5,000, and they alleged that they were subjected to inhuman conditions, made to clean home toilets, and also had to endure continued sexual harassment by Selvi’s husband.

Soon, the threats received by Divya multiplied. “I learnt all the abuses in Tamil,” she jests, “The best part was, none of them had watched the film. One caller wanted to know why I’d said derogatory things in my ‘novel’ Kakkoos; another wanted to know how I was let off on bail after being arrested in a ‘brothel’ case.” Threats of acid attack and rape followed; her TrueCaller app identified numbers as belonging to ‘BJP Saravanan’ or ‘BJP Pazhaniswamy’.

Divya’s complaints to the District Commissioner of Dindigul proved futile. “I furnished several sheets detailing the 2,300 calls I’d received, over 700 recordings, and screenshots of messages I’d received on social media,” she declares, “but the DC said it was impractical to act against thousands of callers, and that my complaint would be forwarded to the cyber-crime cell.” Ironically, an FIR for cyber terrorism was soon filed against her by Bhaskar Mathuram, the youth wing leader of Puthiya Tamilagam.

Divya laughs, recalling the charge. “I am the victim, but they called me a cyber-terrorist.” The frequency of calls has reduced now, says Divya, “I’m not using those numbers any longer.” The number she’s using at the moment is private, available only to her close circle of friends, and a few sections of the media. “I usually trust women,” she says.

*****

Mahalakshmi, 27, in a nightdress, and a dupatta slung over her shoulders, stifles sobs as she talks to the camera. Two little children totter about her feet, as Mahalakshmi recounts the death of her husband, Muniyandi, while cleaning a sewage line in October 2015. Muniyandi and another worker, contracted by Madurai City Corporation, had met their deaths in the gutter. Divya, who admits to having been ignorant of the plight of manual scavengers till then, was moved by the scene of the young wife mourning her husband. “Even when everyone shrank away from his body, Mahalakshmi didn’t. She threw himself over him and sobbed,” says Divya in a Lime Soda interview. The filmmaker-activist, who had until then staged protests for various social issues, began to learn about the laws about manual scavenging. “We were there to help the family get their compensation of Rs 10 lakh as per the 2014 judgment, and imprison those who had contracted the workers under the 2013 Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act. While the family received compensation, no action was taken against those who employed the labourers.”

Mahalakshmi, 27, in a nightdress, and a dupatta slung over her shoulders, stifles sobs as she talks to the camera. Two little children totter about her feet, as Mahalakshmi recounts the death of her husband, Muniyandi, while cleaning a sewage line in October 2015. Muniyandi and another worker, contracted by Madurai City Corporation, had met their deaths in the gutter. Divya, who admits to having been ignorant of the plight of manual scavengers till then, was moved by the scene of the young wife mourning her husband. “Even when everyone shrank away from his body, Mahalakshmi didn’t. She threw himself over him and sobbed,” says Divya in a Lime Soda interview. The filmmaker-activist, who had until then staged protests for various social issues, began to learn about the laws about manual scavenging. “We were there to help the family get their compensation of Rs 10 lakh as per the 2014 judgment, and imprison those who had contracted the workers under the 2013 Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act. While the family received compensation, no action was taken against those who employed the labourers.”

Kakkoos features many personal narratives like that of Mahalakshmi – everyone who is, or who has been working as a manual scavenger, or whose family member has worked, or works as one. Most of the stories are haunting, and the visuals of workers wearing telltale neon jackets, scooping garbage, cleaning the roads and toilets, are steeped in everyday reality. A corporation worker in Tirunelveli, with a mundaasu and an earring, talks about collecting medical waste without safety equipment while another in Trichy talks about clearing corpses of stray animals. A woman worker in Madurai, neatly dressed with a smear of holy ash on her forehead makes a rhyme out of it.

“Panni sethalum naanga thaan, peruchali sethaalum naangathaan, anaadhai pinamukkum naangadhaan.”

[Pigs, rats, unclaimed human corpses – we clear all of them]

A younger woman from the same city, her prim blue sari clashing brilliantly with the neon cap on her head recalls an instance when she was told to clear the corpse of a dog. “I thought it had just died,” she says. But the corpse was several days old, putrefying, with worms feeding on it. “We covered it with a newspaper, and buried it with our hands.”

I couldn’t eat for a day, she tells the camera, pausing between shifting garbage. When the anchor – presumably Divya – asks her if she had brought this up with her supervisor, the worker reveals the unsympathetic, often inhuman conditions she has to work under. “We did,” she responds, “but they said, ‘you signed up for this job knowing what it would entail, why are you complaining now?’”

Divya soon found in her research that while on one hand the number of sanitation workers shown by the government did not tally with the records, 90 percent of them in the state were women. As reported by the Deccan Chronicle:

“She soon understood why Tamil Nadu government insisted that there were just 329 manual scavengers in the entire state. (13,000 was the number of sanitary workers under CITU in Chennai city alone.) “More than 90 percent of its labour force was recruited as contract labourers. This has allowed government agencies like Railways to technically claim that it has not employed manual scavengers,” Divya said. There were other insights that Divya gained. She discovered that 90 percent of sanitary workers were women. More shocking was the realisation that the families of sanitary workers were sold food waste from nearby hotels.”

In the Lime Soda interview, she declares that one cannot talk feminism without addressing the struggles of these women. Women workers often have to endure physical and sexual abuse. A worker in the documentary reveals that the neon jacket that she wears is what protects her. “When they see this jacket, they don’t dare approach us,” she says. Another woman in Thiruvottiyur recalls an instance when a supervisor wanted to know if she had a husband. “He wanted to know if I’d be his mistress,” she bellows at the camera. “It’s just been a month since he joined, and he’s already been asking women out. Periya Manmadhana nee?” [Are you as handsome as Manmadha?].

*****

Ramalinga Mills, a textile mill situated six kilometres south of Aruppukottai, Tamil Nadu, presently employs around 3,000 workers. The settlement around the 50-year-old factory is what Divya identifies as her birth place. Her parents worked at a cotton mill, and Divya, in an interview, remembers being incensed by their working conditions. “I always had questions about class politics watching my father being exploited at the mill, so I was naturally inclined towards it,” she says. After reading up on Periyar, Ambedkar, and Marx, she joined leftist organisations back in school, and had been a part of several protests – from Kundankulam to Tamil Eelam during law school. A fan of alternative cinema, Divya briefly dabbled in Visual Communications before pursuing law. “They have revoked my license now,” she reveals when we talk, “so my BA.BL; certificate is useless.”

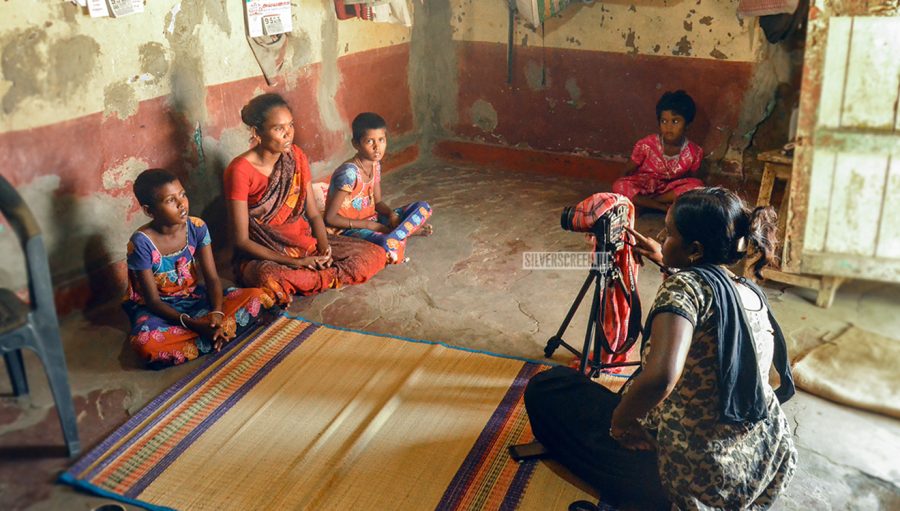

Divya, in the Lime Soda interview, declares that she hadn’t trained in filmmaking. And making Kakkoos, if anything, drained her finances. “We had no producer, obviously – so if we had Rs 1,000 on a day, we’d shoot,” she says on the phone. Work on the documentary began in October 2015, and was wrapped up in January this year. “I pawned my jewellery, and then wrote a post on Facebook following which I received donations from friends. It cost Rs 3,50,000 to make Kakkoos; it seems incredible that one can produce a movie in that budget, but we didn’t have to pay anyone, and we couldn’t use any means of transport apart from two-wheelers.” Over a year and a half, she had collected 92 hours of footage, which was then compressed into an hour and 45 minutes. Getting people to talk to her for the film was a task in itself, but Divya declares that since she was a familiar face in villages, it was easier to convince workers to open up. “Initially, I travelled to their houses without a camera,” she explains, “I cannot land up and rattle off a prepared list of questions. It wouldn’t work that way. So I had to develop a rapport, find out what ails them… you have to be a part of their lives. Not as a filmmaker or to source material for your PhD thesis, but as an activist.”

Divya, in the Lime Soda interview, declares that she hadn’t trained in filmmaking. And making Kakkoos, if anything, drained her finances. “We had no producer, obviously – so if we had Rs 1,000 on a day, we’d shoot,” she says on the phone. Work on the documentary began in October 2015, and was wrapped up in January this year. “I pawned my jewellery, and then wrote a post on Facebook following which I received donations from friends. It cost Rs 3,50,000 to make Kakkoos; it seems incredible that one can produce a movie in that budget, but we didn’t have to pay anyone, and we couldn’t use any means of transport apart from two-wheelers.” Over a year and a half, she had collected 92 hours of footage, which was then compressed into an hour and 45 minutes. Getting people to talk to her for the film was a task in itself, but Divya declares that since she was a familiar face in villages, it was easier to convince workers to open up. “Initially, I travelled to their houses without a camera,” she explains, “I cannot land up and rattle off a prepared list of questions. It wouldn’t work that way. So I had to develop a rapport, find out what ails them… you have to be a part of their lives. Not as a filmmaker or to source material for your PhD thesis, but as an activist.”

For Muthulakshmi, a woman who lost her husband when she was seven months pregnant, Divya and company had hosted a valaikaapu (a traditional baby shower). “From depositing their compensation in the bank, I do everything for them. I can’t just move away after I’ve gotten footage.”

Filming too, wasn’t easy, for Divya had to brave sanitary inspectors who’d demand permission slips to shoot, and needless bureaucracy. Kakkoos did happen though, and was filmed and named. A video clip on YouTube details her reasoning behind naming the documentary Kakkoos. When Divya and team were filming in Ramanathapuram, they met with a little girl, all of seven, whose family, right down to the grandparents, were sanitation workers. “When I asked after her name, her first impulse was to say ‘kakkoos’, as that’s how her family has been branded in the village,” reveals Divya, “The child’s name was Muneeswari.”

*****

In Kakkoos, Divya primarily attributes the plight of sanitation workers to caste hierarchies. The workers, she says, belong to a few Dalit castes, and those featured in the documentary, identify themselves as Arunthathiyar, Ottar, Pallar, Harijan, Kaatu Naicker, Kuravar, Chakkiliyar and Adi Dravidar. The mortal remains of Muniyandi, who died a pitiful death in the sewers in Madurai, were not allocated a freezer in the mortuary as he was a ‘Chakkliyar’.

The workers, branded by caste, with a profession thrust on them, have not learnt, or have no access to learning any other trade despite the 2013 Act that calls for ‘rehabilitation of manual scavengers’, and subsequent vocational training. Divya details in her documentary that a man in Pazhani had immolated himself when the corporation fired several workers. Even those willing to switch occupations, the documentary shows, are barely given a chance. A young man, who identifies himself as a ‘Chakkliyar’, recounts his experience while applying for a job. “I was questioned about my caste, and when I told them, I was immediately asked if I would be interested in a house-keeping position,” he says.

Technology exists, to put these workers out of misery, but when a proposal was put forth by an environmental engineer from Guindy, the Chennai Metro Water Board, says R Anbuvendhan, President of Sanitary Workers Union, shot down the idea as the motors for the machinery were said to cost around Rs 1 lakh each. “But the problem is not money,” Divya emphasises in our conversation, “it’s jaadhi (caste).”

Technology exists, to put these workers out of misery, but when a proposal was put forth by an environmental engineer from Guindy, the Chennai Metro Water Board, says R Anbuvendhan, President of Sanitary Workers Union, shot down the idea as the motors for the machinery were said to cost around Rs 1 lakh each. “But the problem is not money,” Divya emphasises in our conversation, “it’s jaadhi (caste).”

Anbuvendhan also explains in the film that in response to a case that he had filed in the high court to provide safety gear for workers, the corporation brought together women workers from several divisions, presented them with safety gear on camera, and took them away when the shoot was done. A worker in khakis in Thirumangalam corroborates Anbuvendhan’s tale.

That’s why, Divya, who is with the CPI (M-L) says, mainstream parties like DMK and AIADMK will not stand in solidarity with her. “Caste doesn’t belong in their manifesto,” she adds.

Ironically, Dr Krishnaswamy, who founded the Pudhiya Tamilagam party in 1998 to represent Dalits and other marginalised groups, is spearheading the hate-wave against her, Divya alleges. The reason, as Divya details in an interview to The News Minute, is because he belongs to the same Pallar community as Chitra Selvi, the dean of Anna University whom she had accused of employing manual scavengers. Krishnaswamy has filed a complaint against Kakkoos, in addition to several other cases that have been registered against her in Tamil Nadu. All of these complaints, Divya says, carry the same lines, accusing her film of “threatening the sovereignty and integrity of India”, and her of being a terrorist, but have been registered by different complainants (and addresses).

“Krishnaswamy’s grouse is that he doesn’t want to be compared to Dalits,” Divya declares, “He says, ‘Don’t insult me by calling me a Dalit or compare me to Ambedkar, we are all Devendra Kula Vellalar (Pallar)’. He wants to be included under ‘Other Backward Castes’ (OBC). This isn’t Dalit opposition, for Krishnaswamy doesn’t want to be identified as one. His head is full of Brahminical ideology.”

Dalit groups, Divya says, are celebrating the film, which also shows a few Dalit activists who had obtained ‘commissions’- a sum from the compensation awarded to families of the victims. From the compensation given to one of the two workers who had died in October 2015, a Dalit activist demanded Rs 50,000 as commission. “Many said that I had criticised Dalits, but if I had to show it as it was, otherwise it would be a droham (betrayal) to the people whom I’m fighting for.”

The documentary features activists like Bezwada Wilson, recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay award and National Convenor or Safai Karmachari Andolan, Padam Narayanan (who talks about the recruitment process of manual scavengers still followed everywhere), and the head of the Sanitary Workers Union, R Anbuvendhan, speaking up about the measures that they had taken to eradicate the social evil. But it doesn’t feature anyone from outside the filmmaker’s political circle. “This is not about journalistic ethics or whatever,” says Divya, “I have my own politics, my agenda. I am not central, I am left. I am the voice of the people. That’s why I didn’t want to feature any official in the film. I had enough things to cram in it as it is without bytes from them. I wasn’t ready to do that.”

*****

Recommended

The opposition aside, Divya also had support from unexpected quarters – that of Irom Sharmila at whose wedding Divya was a bridesmaid. “Soon after I was arrested in July, Sharmila and her partner had watched the movie, and the next morning, she posted a video in support of me. We began chatting then, I didn’t know her personally earlier. She announced at a solidarity meeting organised for me that I would be her bridesmaid. I was pleasantly surprised,” declares Divya, “My case was going to be heard in court on the same day (August 16) as her wedding, I was wondering what to do when I was later told that her wedding has been pushed to the next day. I was happy; the high court also awarded a four-week stay on the case. As soon as she spotted me at the wedding, she held my hand in a show of support.”

*****

The few workers in the film, who had threatened to commit suicide on being removed from their jobs, are well and alive, Divya says when I ask after them. “They are still into manual scavenging – at private homes.”

Mahalakshmi, whose husband Muniyandi died after inhaling toxic gases in a sewer in Madurai, no longer lives in Madurai, though. Having received a compensation of Rs 10 lakhs, the young widow, along with her two little children, has moved to her parental home near Sankarankovil, Tirunelveli.

Watch the documentary here:

*****