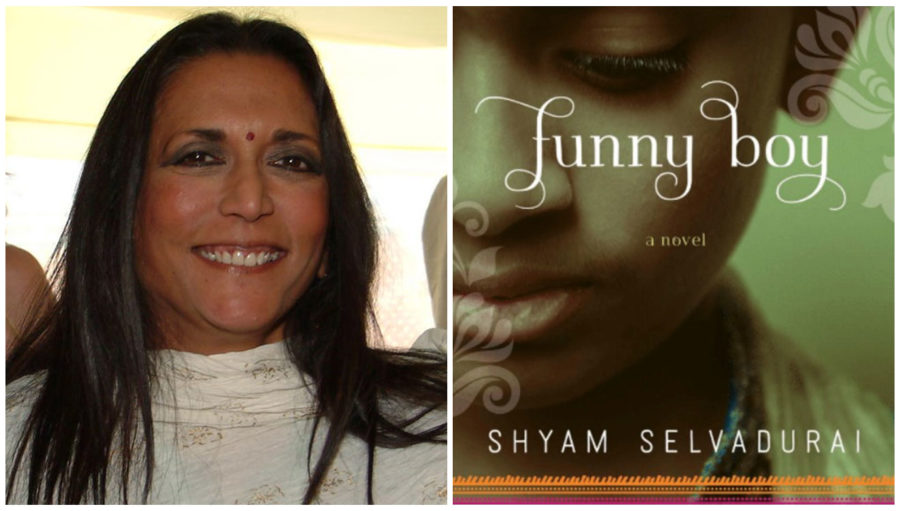

Funny Boy, Academy Award nominee Deepa Mehta‘s movie adaptation of Toronto-based author Shyam Selvadurai’s 1994 novel by the same name, has faced criticism from the Ilankai Tamil (the largest Tamil minority group in Sri Lanka) diaspora after the trailer of the film was released in October 2020. The community has criticised Mehta’s film, which was chosen to be Canada’s official entry for Oscars 2021 in the international feature film category, for the “erasure of Tamil identities”, and lack of Tamil representation in a film about the Ilankai Tamil community.

Last week, the Queer Tamil Collective, a collective of queer Tamil artists, activists, and educators, launched an online petition opposing the film and Mehta’s “irresponsible filmmaking practices”. The petition has garnered over 2,000 signatures. “Mehta’s Funny Boy insults Tamils with the sloppy Tamil spoken in Funny Boy while arrogantly submitting the film as a Tamil language contender at the Oscars,” reads the petition which also criticices the filmmakers for not putting in any effort into casting Ilankai Tamil actors. The petition calls out Mehta for collaborating with Sri Lanka’s “genocidal” regime and accuses her of unacceptable “casting practices, rendering of Tamil history, language, and representation.”

But the problems with Mehta’s Funny Boy run deeper than just lack of representation and inaccuracy of the language used in the film, say Eelam Tamil activists, artists, and writers. One especially thorny issue has been the casting of actors that belong to Sri Lanka’s majority Sinhalese in some of the lead roles.

In response, Mehta has said that it was more important for her to represent the queer community correctly by choosing an openly out actor, be it Tamil or Burgher or Sinhalese, and has cited difficulties in finding an openly out Ilankai Tamil actor to play the role of the lead. This response has been met with anger and disappointment from the Tamil community, many of whom have accused Mehta of handling their concerns dismissively.

What Funny Boy, The Book, Means To The Eelam Tamil Community

Funny Boy is the story of a queer, upper-class Tamil teenager, set against the background of the Black July riots of 1983 in Sri Lanka that resulted in the death of between 400 and 3,000 Tamils and triggered a bloody civil war between Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority and the Tamils that lasted 26 years, and sent thousands of Ilankai Tamils into exile.

Sunthar Vykunthanathan, a Tamil Canadian comedian and writer, told Silverscreen India that “the book is part of the Toronto District Board high school curriculum and as a queer Tamil Canadian it has meant so much to me. That is why it is so hurtful. The people who play the role are not only not Tamil but are the ones who oppressed us. It’s aggression towards us which says ‘you’re not even good enough to tell your own story’. Mehta knows to play and perpetuate these ideas in western society that we are all monolithic, that we are all the same. We know we are not.”

Vijay Saravanamuthu, a spokesperson for the Queer Tamil Collective said that the book was the “first mainstream recognition and affirmation” for the Sri Lankan Tamil queer community. Speaking to Silverscreen India, Saravanamuthu said, “Part of the reason why there’s so much controversy around the film is that the book is meaningful to so many of us. There were great expectations and excitement to finally see that on-screen. But as more information came out about how this film was made, it was very hypocritical. Because, on the one hand, Deepa Mehta is portraying herself as a humanitarian who wants to show the oppression but this production is reproducing the same kinds of erasure and violence of the queer Tamil identity that she is claiming to tell in the film.”

Issues With The Tamil Language Spoken In The Film

Eelam Tamil researcher and writer Sinthujan Varatharajah, one of the most vocal critics of the film, when discussing the problematic Tamil language pronunciation in the trailer of the film said, “It is essential to portray people as accurately as possible. If that does not work, one can find alternatives to that. There is an importance here not just in representing Tamil people properly but not substituting Tamil people with Sinhalese people. She could have used Muslims who are also Tamil speaking and that would be much more sensible and also less work. You won’t have to coach or train them.”

Varatharajah compared the casting in the film to using a German actor to portray a Jew in a movie about the Holocaust. “It’s the question of would you use Germans to play Jews? You definitely should not replace the oppressed with the oppressor, that’s the core of it,” they said.

The Canadian Tamil Congress, an organisation of Tamils in Canada, met with Mehta to discuss the issues the Tamil community has had with the film. During the meeting, Mehta indicated that she was aware of the “problematic nature of spoken Tamil in the film” and that “past efforts to correct this had been stalled because of the pandemic and various other factors”. She noted that even though the trailer was produced with “unacceptable spoken Tamil, the required audio changes are currently underway to rectify the phonetic mistakes throughout the film and the final movie will be released with the changes implemented.”

Mehta tried to address the language issues by outsourcing the dubbing to India. Sharanya Manivannan, a Chennai-based Ilankai Tamil author, was approached by a director from the Chennai based Tamil film industry to help with fixing the Tamil language issues in the film.

Speaking to Silverscreen India, Manivannan said, “I was roped in with an agenda in mind, one that would superficially “correct” the issue but without addressing the harm done at all. I do not think it was Mehta’s agenda. I think that out of defensiveness, she looked for support in the wrong place.”

Manivannan was contacted on November 6 and a screening of the movie was held for her the next day. “I found out much later that the discussion about dubbing actually began in Canada a few days prior,” she said. “Outsourcing to India was a mistake, and possibly indicates an unwillingness to engage with the people directly affected by the events in the film. I believe that following the failure (of the effort to outsource the language correction to India), dubbing was done in Canada,” Manivannan added.

Varatharajah, whose family fled Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the ’83 anti-Tamil pogroms, said that “the mobs would stop cars during the riots and ask Tamil people to pronounce a word. If they had a Tamil accent, they would be taken out, sometimes a tire was placed around their neck, and then it was burned. During that time, language is what exposed you, language is what harmed you, and it is also what killed a lot of people. Then to have Deepa Mehta being so insensitive while making this film, it’s all a showcase of deep disrespect.”

Saravanamuthu explains the Eelam Tamil language is central to the reason why they were being persecuted. Recounting the horrors his parents faced in the ’83 riots, Saravanamuthu said that when Tamil people were cornered by a mob, the only way for them to not be killed was to speak with a Sinhalese accent. He said that the Tamil accent in the trailer is “the Tamil spoken by Sinhalese people”. And for him, hearing Tamil spoken with a Sinhalese accent brings back memories of the slaughter of his people during the riots.

In late October, Canada selected Funny Boy as its entry in the International Feature Film entry for the upcoming Academy Awards as a Tamil film. The language requirement, which is among the criteria that need to be fulfilled by an international film to qualify for the Oscars, says that a “minimum of half of a foreign film’s dialogue has to be in a language other than English”.

Both Manivannan and Varatharajah criticised the move. Manivannan said, “It was absolutely wrong to call this a Tamil language film thereby gaining eligibility for the Best International Language Film category at the Academy Awards. If it was supposed to be a Tamil film, it should have treated the language with respect from the start and represented the particular communities whose history it captures far better.” Varatharajah criticised the language as well, saying “if it is a Tamil story, it needs to be in Tamil, but when the first trailer was put out people could notice how absurd the Tamil was.” They also criticised Deepa Mehta for not making any effort to speak to the Tamil community. “It shows how uninterested she is in Tamil people’s stories,” they said.

The film has since been released on CBC TV and CBC Gem on December 4, and Vykunthanathan says, “minus the one character they have redubbed, the Tamil is still awful.”

What language is being spoken here ? Because it’s not Tamil. #Funnyboy is contending as a foreign language film by making up a language of it’s own. #funnyboythefilm pic.twitter.com/MSjdkVZ4iz

— சுந்தர் / sunthar /🌞 (@suntharv) December 5, 2020

Mehta’s History With Sri Lanka

Though Funny Boy is the first time Mehta shot in Sri Lanka for a story that is local to the land, she has shot on the island previously for her films Water (2005) and Midnight’s Children (2012).

Midnight’s Children was filmed in Sri Lanka in 2010 and 2011, a period of tumult in the country after the brutal suppression of Tamil protests by the Rajapaksa regime. Mehta, under pressure from Hindutva forces in India, chose to film in Sri Lanka, angering Tamil activists. Varatharajah first criticised Mehta in an article they wrote seven years ago. “Deepa Mehta was willfully helping whitewash the regime accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity and genocide. She couldn’t film the movie in India because of the Hindutva pressure, so she looked for an alternative location which ended up being Sri Lanka, which ironically is run by a fundamentalist government,” they said.

Mehta, Varatharajah said, “was in Sri Lanka in 2010 meeting the president and arranging her film at the same time when Arundhati Roy, Noam Chomsky, and so many other cultural and political activists were boycotting Sri Lanka.” They attributed the protests against Funny Boy to Deepa Mehta’s relationship with the Sri Lankan Government, and how in a movie about Tamils, she has replaced Tamil people from her cast and replaced them with Sinhalese actors. They described this as traumatic because the Sinhalese community is the community responsible for violence against Tamils, going back again to the theme of an oppressor playing the oppressed.

Saravanamuthu expressed similar sentiments, questioning how Mehta could have gone to Sri Lanka in good conscience when Tamil people were being slaughtered. “She even specifically thanked the Sri Lankan army in the film Midnight’s Children,” he said and questioned why it was acceptable for her to come back to the island and tell the story of the same slaughter she ignored then.

Deepa Mehta’s Response To The Criticism

After initial criticism about the lack of Tamil representation in Funny Boy, Mehta told the Canadian press that the film’s team spent over a year casting for the story. She said initially they had chosen “some great Tamil actors”, but they were unable to act in the film “due to family issues and visa problems” and later ended up with a “cast made up of 50 percent Tamil actors, and almost all of them Sri Lankan.”

In an interview with the Daily Mirror’s Easwaran Rutnum, Mehta said that her team approached many Tamils not only in Sri Lanka but also in Toronto, New York, and London. She also explains that the Tamils in Sri Lanka were “slightly apprehensive about being associated with a book and a film that had a gay topic.”

Supporting the claims of Mehta, Tamil-Canadian actor Suthan Mahalingam posted a video saying the director did try to cast Tamil actors, and that he was cast as a Tamil character in Funny Boy but was unable to accept the role.

But Varatharajah and the Queer Tamil Collective pushed back against Mehta’s claim. If there had been open casting calls, they would have known, because the Queer Tamil community is tight-knit. Vykunthanathan said, “The queer Tamils in Toronto were not approached because we would have heard about it. So, she is using this to further justify her decisions.”

On Saturday, Mehta told the online magazine LiveMint “While casting Arjie in Funny Boy, it was important to me that the actor was gay. In Sri Lanka, where being queer still bears a criminal charge, casting an openly gay Sri Lankan was most important. Arjie’s coming out had to be visceral, it had to go beyond acting. I wish we could have found the right Tamil actor but unfortunately, it didn’t work out,” and “There is no point casting someone politically correct who can’t act.”

Varatharajah says Mehta has been “dismissive in terms of her responses. I think she is insinuating (in the Daily Mirror interview) that homophobia is so widespread among Tamils but in reality, it is widespread among all societies. To blame Tamil people for her not having done her work properly is a perverse dynamic,” they added. The Queer Tamil Collective’s online petition accuses Mehta of “pitting gay identity against Tamil integrity,” erasing the lead character’s doubly marginalised identity of being both gay and Tamil.

Vykunthanathan, who is an openly queer Tamil comedian, says the voices who have been critiquing the film have been shamed and gaslighted by Mehta. “I talk about my sexuality and being queer on stages in Toronto, London, and New York while performing in front of an all-Tamil audience who have welcomed me with open arms. I think her statements are further perpetuating the idea that homophobia is the reason for her mistakes. And I think that is awful,” he said.

In the interview with the Daily Mirror, Mehta attributed a lot of the criticism to the people living outside of Sri Lanka, and said: “if we care so much, we should be back in our country and fighting.” Mehta’s remarks in this and other interviews have further amplified the criticism against her for not understanding the feelings of the Tamil community. Vykunthanathan said, “Mehta has shown in her repeated violence through her words in her interviews that she does not have a clue what it is like to be a Tamil from Sri Lanka who is unable to go back, unable to speak up for their family members. In fact, one of the actors she had originally cast, could not even go to Sri Lanka because of their refugee status. There’s nothing more ironic than that.”

For her to say that “we should go back” is perpetuating western ideas where we hear “If you don’t like it here, go back to your country,” he said.

What Do The Sri Lankan Tamil Groups Want From Deepa Mehta?

While Varatharajah is asking for a boycott of the film, the other activists want Mehta to engage with them and recognize the erasure of their identities. They would like Mehta to acknowledge the issues with the production and apologise to the community.

Saravanamuthu, speaking for the Queer Tamil Collective, echoed the sentiments of most activists. The Queer Tamil Collective wants people to know that even though this might be a beautiful film, the production has been “instrumental in erasing us and perpetuating the violence against us.” He pleads for engagement from the filmmaker. “Why is this film violent towards us?” he asked, “Why can’t Mehta listen to us? Instead of coming at us with arrogant dismissals, we ask for her to actually engage and be open to listening as to why this project is problematic.” He seeks an apology from Mehta as well because he argues that the Tamil community was disrespected during the production, which actually put money, jobs, and all focus into the hands of their oppressors while “claiming that it is a story about our liberation.”

Recommended

Beyond an apology, “which is certainly warranted,” Mehta can find a “meaningful way to rectify the damage by helping organisations that work on minority issues in Sri Lanka, said Manivannan. Production companies and platforms like Netflix should give the same importance that they do to Western marginalisation when making movies about oppressed communities, said Varatharajah. “You can’t just be like “every brown person is the same”. It’s casteist and colorist,” they said. Varatharajah would like Mehta to “speak about the fact and apologize. That’s all. Mehta has done what she has done, but there needs to be accountability.”

Funny Boy will release on Netflix on December 10

(This article will be updated when Deepa Mehta and Shyam Selvadurai respond to our mails)