There was a day in 2012 when Sunny Mathew walked into his house in Pala, a town 146 kilometres from Kerala’s capital city of Thiruvananthapuram, to realise that his house was choking with shellac records and gramophones.

In the past, he had ignored repeated pleas from his family members to clear the space. Now, he realised that he had no choice but to create a few rooms or a building to host his expansive collection.

A year later, Sunny realised the worth of his collection at an exhibition-cum seminar in Kozhikode as several people displayed an interest. Based on their response, Mathew decided to go construct extra rooms.

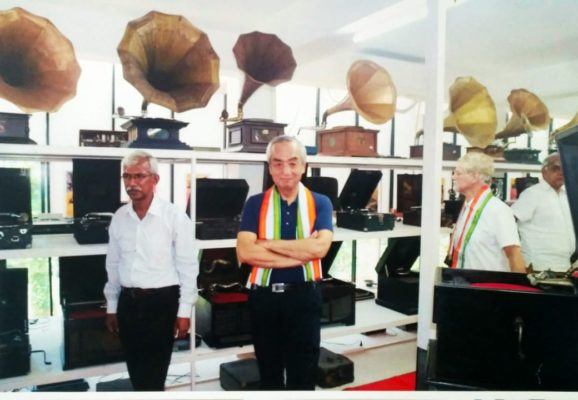

On January 25, 2015, Sunny’s Gramophone Museum and Records Archive opened its gates to visitors. It became the first and only museum dedicated to the history of records and gramophones in India. The three-storey museum has 1,10,000 records and more than 260 gramophones, recording models and guest rooms for visitors.

Collecting such antiques is an investment with no monetary returns for Sunny. He takes care in preserving these musical parts of history. The museum building is covered with reflective glass and packed with de-humidifiers.

Till 2012, Sunny worked as divisional manager at the Kerala Forest Development Corporation. Now, he is a full-time collector, repairer of gramophones and museum owner.

His interest in gramophones was initiated at a flea market in Madurai in Tamil Nadu, he says.

Broken machine, inquisitive mind

“I was working in a place near the Tamil Nadu border in the mid-80s and the closest town to travel to was Madurai at that time. I did not have much to do and visited a flea market. This is where I saw a gramophone with a couple of missing parts in the fixture of the external horn. I was interested in carpentry and had the experience of working with machines in the past. Seeing the gramophone there however, left me interested in the device forever,” Sunny says.

Over the years, he added rooms and cabinets for his growing number of records and gramophones. In 2012, the house was overflowing with timber, air-tight almirahs. Many people encouraged him to pursue the latent idea of a museum.

The swanky museum shares a common wall with his house and his life. The house faces south, while the museum with the ultra-modern exterior, housing antiques faces east. The entrance to both the buildings are separate.

Unlike the arrangement of collections at his home, the collection in the museum is strategically divided. The first two floors are dedicated to records and books, while the top floor showcases some of the oldest gramophone models.

Over time, Mathew says he has amassed a collection of precious records. This includes six record albums of Mahatma Gandhi from 1948, Netaji’s and C Rajagopalachari speeches. He has records from 1898 and 1899 in his collection too.

The top floor of his museum has a collection of spare parts of gramophones which he collected from Seethaphone Company (established in 1923), a Bengaluru-based firm that was assembling gramophones from imported parts.

He also owns record sets of Bengali dramas like Bilwamangal (directed by Rustomji Dhotiwala), and Ali Baba from the 1910s, in sets of 16 and 17 records.

Sunny says that is important to be passionate and informed when running a museum. However, it is also important to have money and climate on your side, he says.

Optimal conditions

“I once remember my German friend asking me how I have maintained my museum in a place like Pala. It is very wet and humid here. One needs to control the temperature inside the museum to maintain the records and gramophones for a long time. Hence, I turned to fixing an air-conditioner and a de-humidifier. This expenditure is fairly expensive,” he says.

Initially he didn’t charge entrance fees from visitors, but realised that people were unwilling to contribute towards the maintenance in the donation box kept at the entrance. “They only came here to click selfies,” he says.

The curator soon decided that the best way to go would be to book slots in advance for groups genuinely interested in the collection.

“A part of the running cost is met from donations from visitors. Since the expenses is to be met from my pocket, it was becoming hard to maintain. The frequency of opening the museum was reduced from keeping it open for seven hours through the year to about 100 days in a year. This further reduced to 52 days. Provisions for opening on pre-appointed time and date was implemented. This helped reduce the electricity and cleaning charges,” he says.

The cost of buying and maintenance has deterred people from buying gramophones in the past. It is one of the main reasons why owning gramophones has never been accessible to people from low-income backgrounds, he adds.

Going back in time

“In my childhood, people used to go to the cinema theatre compound just to hear the records, which was played before the screening of the film. In school and up to the 12th standard, our educational institutions also played records through PA systems. Music was a very costly thing. It was a luxury to own a gramophone, an envious possession till the 1960s,” says Sunny.

According to him, in the 1900s, the price of a three-minute song record was equivalent to the price of at least 80 cents of land. Although single side disks were utilised most often, double-sided ones became the rage in 1907. The price of a record varied between Rs 2 and Rs 5. In 1914, gramophone companies introduced cheaper records which cost Rs 1.25.

When World War I broke out, the import of records to India stopped. The cheap label was withdrawn and for the next 15 years and the Gramophone Co Ltd had a monopoly in India. Things changed in 1928, with an influx of new companies and the 1930s witnessed a music boom in India. But things went back to their former self with the start of World War II, he says.

In 1942, the cheapest HMV model gramophone cost 50 months’ salary of a school teacher in India, he says. In the next 10-15 years, prices came down and a primary school teacher could buy the same gramophone model with five months’ salary. Only in the 1950s, middle-class families had access to gramophones and recorded music, he adds

Sunny is interested is in records made both before and after 1947. “The monopoly of the Europeans ceased to exist and the economy became better. Many Indian music companies began entering the market and selling to Indians who had better purchasing power. The record industry was always dominated by the upper-middle classes and elites. It failed to forge its way into a common man’s life,” he says.

Over the years, the cost continues to remain high. Shellac records which cost Rs 5 in 1985, now cost Rs 300 to Rs 1,000. Sunny says he stopped buying them when the cost touched Rs 100.

“Now, I buy records occasionally. Recently, I bought an 1896 record from an auction in the USA for $150 dollars. I spent this amount since this record belongs to the first year of introduction of shellac records, Berliner’s Gramophone record,” says Sunny.

But such purchases do not happen too often, he adds.

A network

Sunny discusses the availability of records and their history through a WhatsApp group meant for gramophone and record enthusiasts.

This includes people like Mohammad Shafi, who has aided and fuelled Mathew’s passion. Shafi runs an exhibition-cum-repair shop for gramophones and musical instruments in Wayanad, Kerala. He has been repairing gramophones for the last 20 years.

“I have known him [Sunny] for 15 years. One day, he visited my shop and asked around. Then we became close friends. I collected many items for him. I have sent some 1,000 records to him. I was there when he was making the museum,” recalls Shafi.

Both these enthusiasts have travelled across the country, looking for gramophone models and records.

During a work trip to Kolkata, Sunny recalls finding a record with the sticker ‘November 8, 1902; sung by Soshi Mukhi and Fani Wala’.

“I don’t think anybody else has a copy of it. A recording engineer had come from England to India to amass a collection of voices from the subcontinent but none of the professional singers back then wanted to be recorded for a gramophone single. They thought it was beneath them. Two days later during a reception given by a landlord, the recording engineer met famous singers- 14-year-old Soshi Mukhi and 15-year-old Fani Wala. This resulted in the creation of this record,” says Sunny.

Recommended

Such trivia has become part of Sunny’s life. He likes narrating these to most of his wide-eyed visitors, who are stunned by his attention to detail.

Even though the museum is currently closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, he still cleans and maintains it with the hope of opening the gates soon. He has also started virtual live streaming programs online showcasing old records and gramophones. “When you do it as a hobby, you will never get tired. It will give you more energy,” he signs off.