Director: Anvita Dutt

Cast: Tripti Dimri, Rahul Bose, Avinash Tiwary, Parambrata Chattopadhyay,

By now, it is expected of Anvita Dutt to wield established Hindi cinema tropes like a Rubik’s cube, to turn and twist them into one coherent body of work. These machinations may not work every time, but they always have something to say. In short, Anvita Dutt, now, is a genre unto herself in Hindi cinema – a lyricist with that frisky flavour, a biting truth-teller in her dialogues (Queen among others), and a woman who contorts genres into fantastical reincarnations in her screenplays (Shaandaar and Phillauri).

She’s already re-written Radha — of the Radha Krishna fame — into lyrics that reinforce the might of Radha as an all-encompassing authority (the one who wants more!) against the celestial Krishna, while ‘London Thumakda’ is a satire on the mid-90s NRI cinema and its wedding videos, incidentally a genre mainstreamed by one of Dutt’s early employers, Yash Raj Films.

With Bulbbul, Anvita Dutt not only reunites with her Phillauri producer Anushka Sharma but also takes the director’s chair. What we get is another reworking, richly imagined with colours that pop out of the walls of mansions and skins of the actors, Dutt transporting us into late nineteenth century Bengal, a time of Tagore, this is clearly not a coincidence, 1901, the year Tagore’s auto ethnographical Nastanirh was published. The book that became Charulata in the hands of Satyajit Ray. A little bit of Ray adds to the mythical parts in Bulbbul.

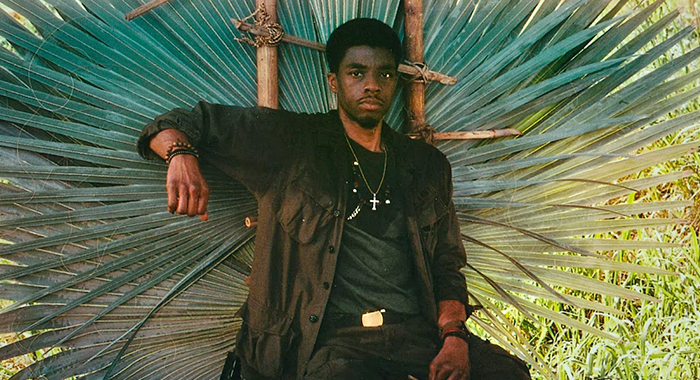

Anvita Dutt’s constant challenge to Indian patriarchal order continues in Bulbbul. While Phillauri began with the groom marrying a tree to ward off the evils in his horoscope. Bulbbul begins with the eponymous child bride. It’s the Bengal Presidency, 1881 and she is hiding low among the branches of the trees. The sun shines bright and gives way for a peek at her feet, accompanied by Amit Trivedi’s anachronistic score. She’s out and about and gets the best view of the incoming groom’s (Rahul Bose as Indranil) entourage, his twin brother Mahendra with an intellectual disability, and a much younger brother Satya.

They arrive in a palanquin with Bulbbul perched on top of them, free like a goddess watching from above. This is in complete contrast to the condition of Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee), who gazes out of tiny crevices to get a glimpse of the outside world. And what does she catch? Well, a palanquin of course! Bulbbul is quickly whisked away from familiar surroundings and brought to her wedding, a ritual she undergoes with the impression that Satya is the groom.

We get Charulata-like shots of these opulent nineteenth century mansions, the view from across the railings as the camera follows someone moving on the other side. And as soon as Bulbbul arrives at her new home — a more opulent mansion that is enclosed on all sides by dense forests — Indranil clears her misconception with a loaded statement, that she’ll understand the difference between husband and brother-in-law once she grows up.

We get that scene again, recreated in front of a large window that looks like prison bars, out of which Bulbbul peers and pines at – the adult Amal..err..Satya (Avinash Tiwary), with whom she shares creative curiosity and unfinished stories.

From here on, Bulbbul takes a sharp turn into the fantastical territory where there are myths to bust with pages missing. There is a witch (chudail) haunting the woods in 1901, killing men. Dutt uses a mix of Bhansali-esque tropes with Gothic stylings, designing the spectacle and suspense required of a gothic romance.

The colours are either deep crimson or blue. The minimal daytime shots cover the warmer aspects of the film — Satya and Bulbbul reuniting, both visiting Binodini (Paoli Dam), Mahendra’s widow, now isolated, and exchanging wisecracks about the way Bulbbul has grown up.

There are also greyer shots like Bulbbul recalling the place where she and Satya go down to pen their stories and bond over shared mythical tales. He suggests that the place must be repainted blue, to reflect the colour of her mother’s home. The film gets cheeky again, when the blue is heavily incorporated in a chilling scene, whose coordinates lie farthest from the idea of home.

Dutt and cinematographer Siddharth Diwan either use the spatial incongruity of the mansion that we never fully grasp or god’s eye view shot of dense forests with the mansion in the middle to lend credibility to the gothic fantasy that they are going for – Binodini even tells Bulbbul in a scene, “badi haveliyon mein bade raaz hote hain”.

An early scene — when Satya returns late in the night and sees the mansion abandoned — is eerie with silence and intrigue, Amit Trivedi fully aware when to tune in and when to tune out. Another scene is after Satya’s departure, when we get a 360-degree view of Bulbbul dividing her time between her chores, her writings and her time in front of the window, waiting.

Dutt and Diwan use mirrors in a couple of scenes involving Rahul Bose when it becomes tough to tell whom we are looking at — Indranil or Mahendra. The idioms of gothic romance are maintained by Anvita Dutt throughout, there are no male saviours and the beguiling charms of the feminine is appreciably used with gay abandon. When Satya too begins to doubt and distance himself from Bulbbul, a lilt accompanies her reply, as if she always knew — “tum sab ek jaise ho”.

Recommended

That line “you are all alike” fits the other myth that Anvita Dutt incorporates to layer her film — Ramayana. After all, this is a film in which Sita sings the crimson and the blues. The mansion is deep within the woods and Bulbbul is essentially held captive. Before an important scene, Dutt cuts to Raja Ravi Varma’s ‘Jatayu Vadham’, a painting that was completed six years before the events of the film. The mansion houses Ram, Raavan and facets of men in the periphery run the gamut (the problematic depiction of a person with intellectual disability in this context requires its own essay).

Including Sudip (Parambrata Chattopadhyay) who plays the Hanuman figure with a meagre deviation from the lore. It’s easy to conflate Satya and Sudip as the Hanuman figures but if we consider Satya as the problematic Ram back from exile, then Sudip is the well-meaning but ultimately powerless Hanuman.

In Bulbbul, Ram commits a grave mistake that Hanuman originally commits in the epic. But this Ram does it due to the impotency that he senses within himself. And Sudip is the one who asks, “What have you done?” Bulbbul is an interesting intersection of Ray’s Charulata and epic Ramayana with gothic romance fashioned in with grace. It leaves us ungratified in a good way. Like Radha, we want more.

The Bulbbul review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreenindia.com and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.