Director: Spike Lee

Cast: Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, Norm Lewis, Isiah Whitlock Jr., Chadwick Boseman

Spike Lee and Quentin Tarantino — it’s difficult to imagine two filmmakers more likely to come to fisticuffs, isn’t it? Theirs is a decades-long feud, which began after the latter’s Jackie Brown (1997) and has shown no signs of letting up over the years. This is one of the reasons why it was tempting to see BlackKlansman (2018) as Lee showing off his prowess at a distinctly Tarantino-esque game — revisionism meets exploitation film, wrapped up in a bouquet of era-appropriate Hollywood checkpoints.

Lee’s latest, Da 5 Bloods, released earlier this month on Netflix, will give further ballast to that theory. A Vietnam War story crackling with allusive imagery and pop culture nous, Da 5 Bloods doesn’t quite reach the heights of some of the director’s early career triumphs — but it comes close.

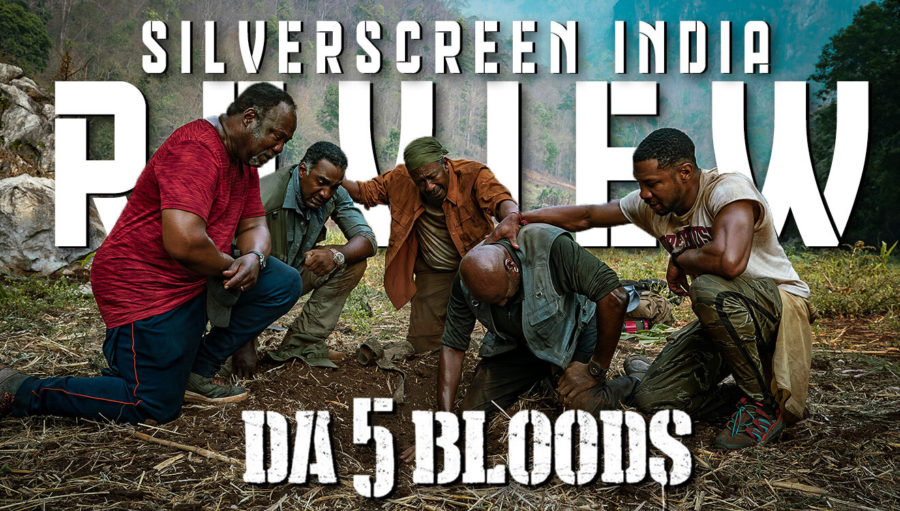

The narrative follows the four surviving members of a US Army squad (who called themselves “the Bloods”) from Vietnam — Paul (old Lee favorite Delroy Lindo), Otis (Clarke Peters), Eddie (Norm Lewis) and Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.) — who travel back to a jungle they fought in to find the remains of their fallen leader Norman (Chadwick Boseman).

They also intend to recover the cache of gold (intended for the native Lahu people, in exchange for their help fighting the Viet Cong) that they had buried there all those years ago and could never recover. Along the way, of course, there are unforeseen developments, like Paul’s son David (Jonathan Majors) turning up to join the Bloods, and Desroche (Jean Reno), a shady French businessman who can apparently help them move the gold.

The plot moves along fairly briskly for the most part, and while the last 20 minutes or so are frenetic to say the last, it’s the strong fundamentals of Lee’s storytelling that elevate this joint.

Right from the first ten minutes of the film, it’s clear that Lee has a thing or two to say about Hollywood’s long lineage of (blindingly white) war movies set in Vietnam. Melvin cracks a joke about “those fugazi Rambo movies” to sniggers all around. And the very first flashback sequence give us two artistic choices that make Lee’s modus operandi clear — first, we see a chopper cutting across the orange Vietnam sky from a distance towards the centre of the screen, a callback to that shot from Apocalypse Now (fittingly, just minutes ago, we saw the Bloods exiting Ho Chi Minh City’s famous Apocalypse Now club). And then, we see that the Bloods are their contemporary selves, beards and bellies; Lee chose not to use different actors or any degree of digital de-ageing.

In Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir Maus, the first section is called “My Father Bleeds History”, for the infinite ways in which the past seeps into the everyday habits of Spiegelman’s father, a Holocaust survivor. Something similar happens to the leading men of a Spike Lee joint. For them history is not a phantom or a fleeting apparition, it is a physical sensation keenly felt every day; the strength projected by a raised fist, the hurt swallowed by a lump-in-the-throat. And because of this, the sight of these old men led by the visibly decades-younger Boseman makes perfect sense. As for the Apocalypse Now/Rambo callbacks, Lee interrupts that conversation by telling us about the forgotten African-American soldiers of Vietnam, like 18-year-old Milton Olive (“a real hero, someone of our blood”), the first black man to be awarded the Medal of Honour in Vietnam.

In other words, Lee’s manipulation of temporality is twofold — the historical portions of his narrative are constantly being intercut with a present-day authorial voice ‘correcting’ the white-centric, mainstream American narrative (backed up by documentary-style footage cameos by Mohammed Ali, Angela Davis and so on). When it comes to his characters, however, he prefers a floating approach that merges past and present together; you know, like the human brain does every single day. These self-aware techniques break the fourth wall in a much more profound way than any number of The Office-inspired Jim-glances. Indeed, it’s only in a bravura Delroy Lindo monologue deep into the second half that we see Lee using conventional meta-technique: Lindo signs off with a defiant fist raised directly at the camera.

These techniques, and how effectively the director uses them here, also tell us about the fundamental differences between Lee and Tarantino. It can be said that both men are deeply invested in a cinema of images in conversation with each other. In Tarantino’s case, however, the conversation itself is highly superficial and refuses to engage in anything but the iconic outlines of the matter at hand. Lee has the thoroughness and the organised approach of an experienced documentarian; despite his visual flair, he’s forever wary of framing history — American history, that is — into too-neat frames.

Recommended

I say ‘American history’ because sadly, Lee is not immune to American exceptionalism. While African-American history is given the close attention that it deserves, Vietnamese characters exist mostly as props and stereotypes, with the notable exception of Veronica Ngo playing the real-life radio presenter ‘Hanoi Hannah’. The Vietnamese prostitute who bears an American soldier’s baby, the ex-Viet Cong little old men, and yes, a literal tour guide, played by Vietnamese martial arts star Johnny Trí Nguyễn. I mean, even a red-blooded Tamil masala action movie like 7aum Arivu used Nguyễn’s presence and martial arts prowess in a far more efficient way.

Apart from this misstep, however, Da 5 Bloods is Spike Lee operating at near-peak levels, a prospect that’s always worth your time.

The Da 5 Bloods review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreenindia.com and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site