Director: Shoojit Sircar

Cast: Farrukh Jaffar, Amitabh Bachchan, Ayushmann Khurrana

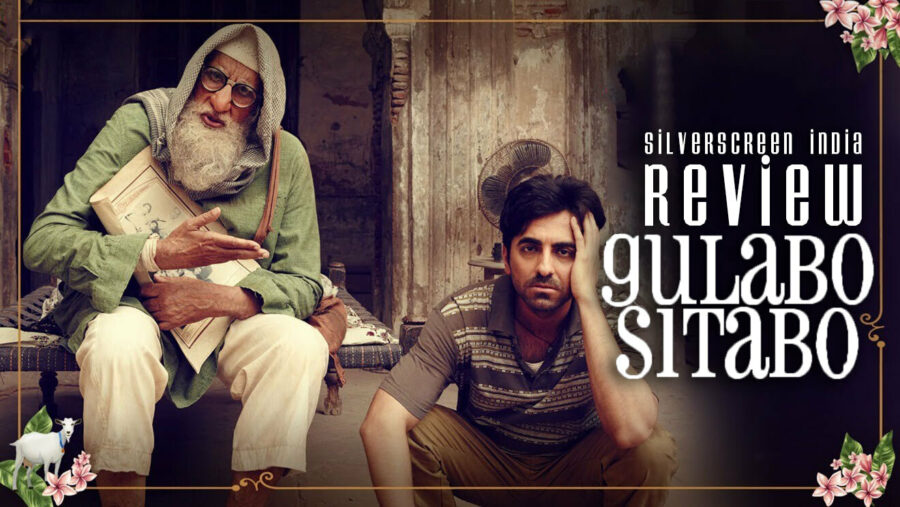

Early in Shoojit Sircar’s Gulabo Sitabo, the camera frames two girls dancing and giggling at the dramatics of the eponymous, bickering glove puppets. The girls numb to the chastisement, forming a straight line with the two, now still, puppets — the puppeteer sitting on the side of the road, against one of the Quaiser Bagh Gates that is a perennial presence in the film. Mirza (Amitabh Bachchan), an almost octogenarian, looks on and leaves a moment before words fall upon him too. He is the acting landlord of Fatima Mahal, a haveli or mansion, with about five tenants paying him non-fixed rent. He takes out petty cash, sells bulbs and stolen whistles out of vehicles, while the real owner of the haveli, the Begum (Farrukh Jaffar), a bitter old woman with chambermaids on call. Like in Piku, another person’s death is awaited, here it is his Begum’s – seventeen years his senior – so that the haveli will finally be his.

Mirza is a towering presence, walking around the mansion like Nosferatu, with the same kind of stuttering, sometimes nutant posture. He also confines his activities to the darkness, removing bulbs or fuses, and much of the first quarter of the film is shot in this darkness with minimal lighting and shadows. It’s only as the film ambles along, we get the other major players and the daylight, the size of the mansion dawns upon us, ensuring that this puppet needs deft controlling and something sturdier than papier-mâché.

Time is fleeting and malleable in Gulabo Sitabo, written by Juhi Chaturvedi. Except for the mobile phones in pockets taken out for a mini photography session on a tree branch, we don’t see them. Different pieces of clothing cover Mirza’s head while the concept of inflation has never hit those parts. In multiple scenes, he lands up on a number with the passer-by’s help – the rent he could potentially receive, the money the mansion could fetch – and drops almost dead. In an excellent scene blending great lines with playacting – like puppets if you will – he wonders about twelve times 2500, the amount he could receive per year and almost takes the panipuri guy’s pot down with him. In the background, we hear the panipuri guy giving a bill for 90 bucks as Mirza steadies and wonders about the rents of 70 and 30 bucks. That’s how time is frozen in Mirza’s head, Begum’s incomplete anecdotes of the time Nehru visited her (“there were only petty thieves when Nehru visited” is infused with meaning) and the way Lucknow is captured as the old city — a relic, a valuable one at that — that is being siphoned off.

Gulabo Sitabo does not shirk away from what it is, a film featuring a Muslim protagonist, a Mirza – the rank of noblemen, maybe a descendant from one of the princes during the time of Awadh, and the film’s gaze is always around the Islamic life in these parts of old Lucknow. A life that the film’s universe breathes in and out as Sircar always keeps an oxygen tank in hand, with wide shots of tall Indo-Islamic architecture by the Nawabs of Awadh, like Chota Imambara after prayers, the prayers in the background always less than 500m away from the film’s soundscape or the horse carriages in the mist of early mornings. Syncretism pervades the visuals of Gulabo Sitabo, a noble Bollywood attempt to bring to Lucknow one of its authentic flavours. Fatima Mahal is a relic that holds a host of tenants consisting of Rastogis and Mishras et al. While Chaturvedi’s writing invades these lives and animates the charged conversations that are always about the mansion and the rent, Sircar and Avik Mukhopadhyay’s camera trolleys around every view of the Mahal from its courtyard and this is not just to observe the various living tenant – from Baankey’s (Ayushmann Khurrana), his mother and sisters, or Mishraji and few others making up the five tenants. In a shot in darkness with a couple of yellow bulbs that light Baankey in the balcony, we notice that a whole railing under the balcony is missing, a hollow open space for a running child to fall through. Or the outside balcony where one side of the wall is absent. A great location when in placed in the context of history and the people living in it, but with kinks to iron out. The interiors of the mansion like Baankey’s room give little jostling space for five occupants, a cot in between, the small television and various paraphernalia, some neat, some untidy in arrangement around the room, with objects resting easy knowing that they’ll never move an inch ever again.

The world of Gulabo Sitabo is secular in its composition, the meaning wielded like a relic, like in India now. Mirza is a physical relic, Baankey runs a flour mill not knowing what organic is, and Gyanesh Shukla (Vijay Raaz) from the archaeology department has more specific interest in relics. Mirza hires a lawyer called Christopher Clark, Bollywood finally writing a role befitting Brijendra Kala, Clark a colonialist relic, after the police wash their hands off saying this is a matter of law and not the police. Damn right! The scenes at the civil court between Clark and Mirza are beautifully composed, with them in his little office between two pillars of the corridor while the sun decides whose face must be lit brighter. In one scene, it is Clark’s, as the lawyer, briefing Mirza on what needs to be done to get the mansion under his name. “Aise haveli ki single ownership nahin hoti” (there cannot be a single ownership of a mansion like this). He talks about finding other living claimants and to find out how many are dead among them, which sends Mirza looking for old photographs and a discomfiting interrogation session with Begum. In another scene, we see Clarke has appointed the street-smart Guddo (an intimidating Srishti Shrivastava often finding her way through swathes of men), Baankey’s sister, as his new assistant. This time, they seem to be happy for a sceptical Mirza, like the job is almost done while the sun shines bright over Mirza’s head. It is an issue of land with various stakeholders – Mirza, his tenants demanding LIG flats in exchange for Shukla’s deal punctuated with a big if (in a great scene with old Lucknow under sunny glow, tea serving Guddo retorts what if we want MIG — middle income group — flats, as she sips the last tea).

In this secular setting, built over the bodies of Mughal kings, vassals and their people, we can feel free to read a whole lot. The lack of space for sizable population, the disenfranchisement of people like Mirza, and the government-real estate manoeuvring waiting to take advantage of a door half open. A lot of logical explanation in this film falls on Guddo’s head while rest of the film never veers away from its black territory but one instance stands out — when villains are explicitly defined — when it is told that Mirza and Baankey are not duelling, the villain is people like Shukla, the agents of the government, this time from the archaeology department distorting the past to create a new future.

Recommended

Bachchan’s gait does seem practiced but it’s all the prosthetic he is wearing that grates. Lalach (greed) is a word thrown around a million times in Gulabo Sitabo but one of the standout scenes, Sircar films with all the tenants and watchful Shukla blocked around a cannon. The tenants ask why here. Baankey gives them the cliff notes version of Asaf-ud-Daula, who had a domineering mother who withheld his freedom, and therefore he packed his bags for Lucknow from Faizabad. In their story, according to Baankey, Mirza becomes Asaf-ud-Daula’s mother, the one they all need to revolt against and erase. What is left unsaid though is that Asaf-ud-Daula, during the famine in late 18th century, started a food for work program by beginning to build the Bara Imambara, providing relief for the working class, an act that gave birth to the saying, “jisko na de maula, usko de asaf-ud-daula”. Sircar and Chaturvedi leave Mirza and Baankey alone to reflect on that.

The Gulabo Sitabo review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreen.in and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.