Homemade, the short film anthology series on Netflix, produced by Chilean director Pablo Larrain’s Fabula, has seventeen directors from around the world making sub-10-minute short films on life under lockdown as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The endeavour captures the global nature of the lockdown and the turns everyday life has taken in different parts of the world, and what could be the short- and long-term effects of living through this time.

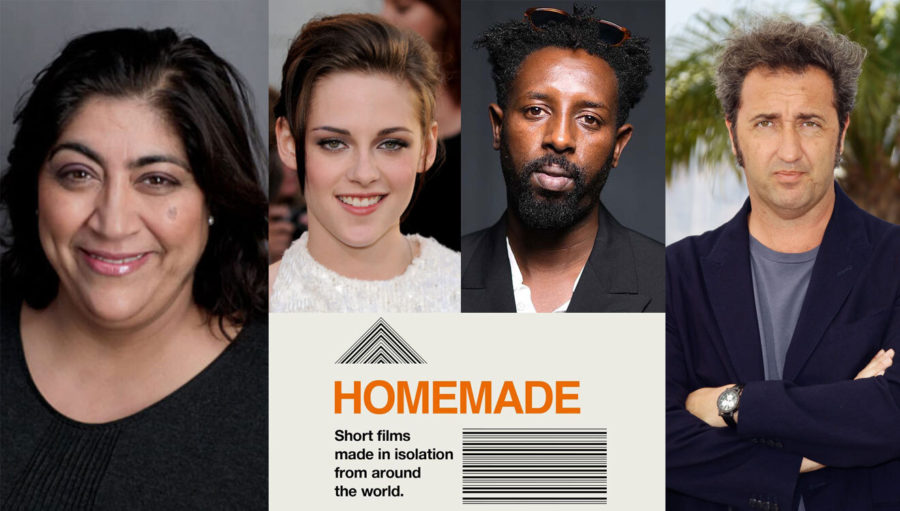

The directors run the gamut: Ladj Ly (Montfermeil), Paolo Sorrentino (Rome), Rachel Morrison (Los Angeles), Pablo Larrain (Santiago), Rungano Nyoni (Lisbon), Natalia Beristáin (Mexico City), Sebastian Schipper (Berlin), Naomi Kawase (Nara), David Mackenzie (Glasgow), Maggie Gyllenhaal (Vermont), Nadine Labaki & Khaled Mouzanar (Beirut), Antonio Campos (New York), Johnny Ma (San Sebastián del Oeste), Kristen Stewart (Los Angeles), Gurinder Chadha (London), Sebastián Lelio (Santiago) and Ana Lily Amirpour (Los Angeles). The series is also a drive through of stylistic choices of the filmmakers, many of them familiar and some of them new.

Watching all seventeen films of Homemade, it is apparent that analysing each film will hardly be a rewarding exercise. The pandemic is global and therefore, Homemade too is sum of all its parts, the individual nuts and bolts revealing something greater about both the pandemic and filmmaking. It reveals the inner concerns of the individual filmmakers, how they see their place in the world and what they want to highlight in their films.

Ladj Ly’s lays the groundwork. Setting the film in Montfermeil, the same universe as his 2019 film Les Misérables, Homemade quashes the notion that this pandemic has been a leveller across the world. With Buzz’s drone shots of working-class apartments and people waiting in queues, the anthology submits that some people are less equal than others and therefore more affected by the pandemic.

This is also reflected in each director’s depiction of a life deprived of daily necessities that widely differs across a ‘privilege’ spectrum. The white directors with films set in Los Angeles, New York, Berlin and Glasgow emphasise personal struggles, the mental toll life under lockdown has been for their characters—adults and children. These films also use a more optimistic lens, either in looking forward to a brighter future or seeing the current situation as blessings of time, ample outdoor spaces with parks and beaches where social distancing is not only maintained but used as a getaway to semblance of normalcy. It’s a major factor that distinguishes some filmmakers/locations from others.

While the more socially aware filmmakers set their films within the four walls, the films set in the first world (or by first world directors) have a way out of those restrictions, in parks and beach side homes. Some films—one set in London—sees this as a chance for children to reconnect with roots or have fun frolicking in car wash or hiking to lakes, a time to be spent with family that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible, others reduce the horror to a metaphor or extend the dystopia further, worse than what it already is.

Amirpour’s film is a more buoyant call-back to her debut film, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. Here, a girl gets away from home during the day, on a bike, to find LA’s landmarks deserted, her ride is accompanied by a dispassionate Cate Blanchett narration.

These films, however, also draw from intensely personal experiences, devoid of embellishments, never sacrificing narrative vigour in the process.

The shorts might have been filmed under lockdown, but they reflect the past and future works of these filmmakers. To no one’s surprise, the European and Middle East/African directors’ films are more political in nature, not only within the imposition of a lockdown but also with the inconveniences of a short film. These films rarely show the outside world, they confine themselves within the home because even a roof above is a symbol of privilege.

One film has a black woman in a tiny home that she shares with her white ex-boyfriend, having just broken up with him. We become voyeurs into her chat group with other black friends, wondering how much of a Karen her ex is.

Children are a constant focus in Homemade, either struggling alone at home, left to fend for themselves and getting hurt in the process, wondering if they are just floating away in outer space, or locked in a room with an imaginary friend, braving through stormy seas in a life of endless struggle to reach a benevolent land as refugee, the lost family’s picture looming in the computer wallpaper.

In San Sebastian, there’s another story of reconnecting with the roots, by way of food, as a man makes a video essay for his mother by trying out her dumplings recipe far away from home. He wonders if she’ll ever get to see it as she doesn’t have a Netflix account. In between all this, Larrain and Sorrentino give a peek into their own mode of working, going for the absurdity with some audacious deadpans.

On the performances front, two actors shine through, Amalia Kassai and Kristen Stewart. Kassai’s is an impromptu musical that she carries all by herself, singing of privilege and humanity’s struggle against the virus. Self-aware that she is communicating from a safe and sumptuous home, she gracefully slithers down the stairs, uses every inch of her home and its contents as props, choosing between twisting them or herself into knots, pretending she’s not alone by hugging a jacket on a hanger. It’s an incredible physical performance on all fours.

While Kassai copes with humour, Stewart’s is a film made of incessant closeups that she holds with flair, her expressions hovering between the knowledge that she’s being watched and also coming to terms with her intangible loneliness. The film is raw, like a CCTV camera focused on Stewart’s anxiety-ridden face and jump cuts from one expression to the next. It’s a face we know—from Stewart’s performances in films such as Clouds of Sils Maria, Personal Shopper or even as Jean Seberg in Seberg last year —one of the best actresses of her generation having mastered this role of a woman in quiet struggle, probably bringing a little bit of her personal into her fiction, speaking for a lot of us as she perseveres to get through night and day, locked up and unable to sleep.

Recommended

Homemade can be a great starting point into the larger works of these filmmakers and actors, almost all of them imprinting their signature in short gasps. It might have been made to capture the lockdown minutiae, but it also shows that cinema waits for no one. As humans, we might be forced to remain contained and distanced for our own benefit but to paraphrase Dr Ian Malcolm, cinema cannot be contained, it breaks free, expands to new territories and crashes through barriers. Cinema..uh.. finds a way.

The Homemade review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreenindia.com and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.