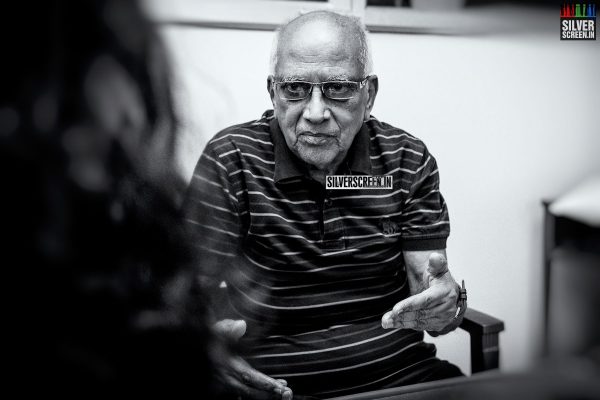

Singeetam Sreenivasa Rao, or Singeetam, as he is fondly known, built his distinctive oeuvre with 56 movies in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Hindi. In 1974, he won a National Award for his second feature film Dikkatra Parvathi. His classic silent film Pushpak (1987) premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and went on to win another National Film Award. No Indian time-travel movie has been able to replicate the success of Aditya 369 (1991). While Apoorva Sagodharargal (1989) is considered an unparalleled technical marvel, Michael Madana Kamarajan (1990) is cult comedy at its finest. At 82, an age when most people retire into a life of relaxation and reflection, Singeetam completed a course on 3D animation. Then he made two animated films: Son of Alladdin (2003) and Ghatothkach (2008).

Stacks of paper and a writing pad lie on the table. An old, yellowing note, encased in a frame, hangs from the wall. Dated December 6, 1972 and signed by India’s last Governor-General, C Rajagopalachari, it is a note of consent, for the cinematic adaption of his short story “Dikkatra Parvathy”. Across the wall hang shields of honour and certificates. There is a bookshelf, full of books in different languages. In one corner lies a vial, with holy water from Jerusalem. Singeetam brought it back to explore the possibility of making a film on Christ.

This is Singeetam’s home.

Nothing about him gives away the fact that he is 85. His voice has a youthful vigour when he starts talking about cinema. Anecdotes, details and names from the distant past are easily summoned. Time hasn’t touched his memory.

“Do you think this interview would interest your readers? I am not a star,” he asks. No sarcasm. An honest, unassuming query.

***

He sees me looking at the piles of papers and says, “I’m working on a couple of multilingual projects. One is with Mr Balakrishna, with whom I made Aditya 369, 25 years ago. I am making a sequel to that, through which his son will be introduced.”

What is your writing process like?

It begins with a concept. I write a storyline.

In India, sometimes dialogue and screenplay are handled by different people. That’s because our movies are very dialogue-oriented. We came from theatre. Visuals have very little role to play because telling the story through dialogue is much easier than experimenting with visuals, which is expensive.

Is that why you made Pushpak?

Is that why you made Pushpak?

Yes, I wanted to challenge that. Unlike in Hindi, Tamil cinema started with talkies. Dialogues were important because audience were mostly farmers and the uneducated class. Those movies were not actually cinematic, but photographed stage plays exhibited using projectors. 85 years later, that basic theatre feel has not gone away from our cinema. But nowadays, young people are changing that scenario.

How important was your experience as an assistant director?

I joined Mayabazar (1957) as an assistant to director KV Reddy. I spent more than 20 years in the industry as an assistant. Today, no one wants to be an assistant. They make short films, and get a direct entry to feature films. That’s clever. Now I feel I wasted my time working as an assistant. It is not necessary to assist someone to learn filmmaking. Those days, we had no other go.

Would you have rather made a short film?

No. I used to think there were rules for everything and I should not break them. Today, grammar in cinema is something to be broken. The golden rule is that there is no golden rule. Everybody breaks conventions.

He talks about legendary American actor-director Orson Welles, who started his career with a radio play about an invasion by men from Mars and went on to make the classic Citizen Kane in 1941.

He [Welles] was a breakout talent. Just like that “Kolaveri” song.

Things have become easier for an aspiring filmmaker. The industry is teeming with new talent. Also, there are mediums like YouTube. A lot of content is being produced.

You don’t think it would dumb down the audience?

Who are we to dumb them down? (laughs) That’s because we think filmmakers are superior to the audience.

It was tougher to be visible during my younger days. Today, if you are talented, you will come out like a spring. Those days were not good. I always believe the present is better than the past. And the future will be better than the present.

What is your least favourite part of filmmaking?

I don’t know. Finding the right producer is hard most of the time. Not all films are box-office hits. There is something called personal cinema, which might fail at the box-office and yet be a great film.

I met Satyajit Ray in Kolkata sometime after he made Pather Panchali. He was a very practical man. Before making a film, he and his friends would make an estimate of how much money the film could make at the box-office. The budget of the film would be decided according to that. He was a shrewd producer apart from being a great director.

Marketing your film is equally important. The most creative filmmakers/artists are the ones who have managed to reach people. Make a good film, people will definitely watch it. If not today, tomorrow. The people who have not reached their audience are average and below average filmmakers, the people who make bad, pretentious film that they call ‘art films’.

What is your favourite part of filmmaking?

Visualising the script (smiles). As I am writing, I have to imagine how it would turn out on screen. Every frame, including the small nuanced expression of the character.

But while shooting it, you might not get it as you had expected. The facial expression of actors, the light conditions or a particular tree that you wanted in the frame. There is that slight gap between what you expected and what you got. The process of trying to get as close to what you had imagined, is the most interesting part of filmmaking. That’s the challenge. Scripting isn’t a challenge. Just going to the location and shooting without a plan isn’t hard. But this is.

Watch some of the films made by Bergman and Akira Kurosawa. You can see how much detailing they bring into the films. Once, at a shoot, Kurosawa told his actor, who was on a horse, “Don’t be nervous.” The actor replied that he was not nervous. But Kurosawa said, “You are. I can see it from your horse’s face. It is sensing your fear.”

But there are also instances of reality surpassing expectations. Films that I did with Mr Kamal Haasan, art director Thottatharani, or the immensely talented PC Sriram are such. I ask for something and they come up with something far better than what I had imagined. I wanted a particular type of hotel for Pushpak. Finally, we found Windsor Manor in Bangalore, and the whole script fell into place then. Such serendipity.

What is the craziest thing you have done to achieve something while shooting?

A lot of things. Because all my films involved craziness. But I have never done anything that insults the actor. Like exploding a cracker behind him to get that expression of fear. That’s insulting his talent. They are good performers and I trust their ability to act.

While shooting with animals and children, you will have to use certain techniques. For a Telugu film, we had to shoot with a grizzly bear. We travelled to Canada, prepared a storyboard and rehearsed the scene with the bear. The first take was all right. The second take, the bear refused to perform. So the trainer asked us to applaud and cheer for the bear. “Good boy, well done!” we said, and the bear did it properly several times without any qualms.

When you were writing Apoorva Sagodharargal, did you know how you were going to execute it?

No! We had the idea and there were no computer graphics to do what we had in mind. We used knee pads, shoes, and made a pit for Kamal to walk through. And another pit for the camera. However, his walking didn’t look right at first. So first, we shot his movements using a small digital camera. He saw the mistakes, practised again and again. It took us a lot of time, patience, and hard work. The best part was that other actors on the set, like Nagesh, they understood how much we were struggling with Kamal’s portions. So even if they didn’t have any scenes, they would be waiting on the sets with their make-up ready. “Don’t worry about us. We will be ready whenever you want to take our scene,” they would say. That was very nice of them. They never lost their cool.

The film was possible only because Kamal was the producer. No one else would have funded this movie. Kamal had done a cameo as a dwarf in a Balachander film. He wanted to do an entire film around a dwarf character. One week after we began shooting for the movie, I felt something was wrong, though I couldn’t diagnose where.

It was the multi-faceted Panju Arunachalam who came to the rescue. We consulted him. He listened to the story. ‘The dwarf should be the hero. He shouldn’t lose,” he said. He suggested that Kamal should do a double role. What Panju told us changed the fate of the movie.

Michael Madana Kamarajan’s climax was inspired from Charlie Chaplin’s Goldrush, wasn’t it?

Michael Madana Kamarajan’s climax was inspired from Charlie Chaplin’s Goldrush, wasn’t it?

It’s a fun sequence. Michael Madana Kamarajan (MMKR) is a modern version of the old folk tale of king, queen and their quadruplets who grow up in different households. Instead of routine chases and stunts, we wanted something different for the climax sequence. The exterior portion was shot in Coonoor and the interior of the house was shot in studio, in a hydraulic set.

It’s not easy to do a film with a lot of actors, is it?

They were all great actors: Kamal, Urvashi, Nagesh, Khushbu, SN Lakhsmi, Delhi Ganesh. Managing the people on the set wasn’t hard at all (laughs).

The real challenge was not to mix up the characters in the story. There are four identical characters who, in many scenes, wear the same dress and appear at the same place. To bring clarity of who-is-who to the narration was difficult. Now when someone is watching the movie they have no confusion about who is who.

Making the dwarf role in Apoorva Sagodharargal was very easy. His physical trait lends him enough attention and sympathy from the audience. But, usually when such a character is there in a movie, his normal-looking twin automatically becomes the villain or the less favourite one. This happens in Kalyana Raman. I had to make sure that the normal-looking Kamal in Apoorva Sagodharargal got equal attention and sympathy.

Veteran director-producer LV Prasad played Madhavi’s grandfather in Raja Parvai and cinematographer RK Krishna Prasad acted in MMKR. How did you convince them to act?

LV had acted in many movies in the black-and-white era. Kamal and I went to his house to ask whether he would do this very affectionate and humorous grandfather role. He was hesitant, but finally agreed on one condition – he would shoot on the first day, see the rushes, and if they were satisfactory, he would continue acting.

Casting people like him gives a freshness to the character. MS Viswanathan acted in Kadhala Kadhala. It’s not easy to act in comic roles. But if the face and body language fits in, fifty percent of the work is done. While other actors have to act, these people don’t have to. Perhaps they can do well in only one or two films. If you keep casting them, they might be deemed as bad actors.

You considered bringing Satyajit Ray on board for Pushpak as a music director?

That was just a thought. We didn’t approach him. For Pushpak, I wanted someone who would work according to my commands rather than someone like Ilaiyaraja who would want to compose music according to their liking. That approach wouldn’t work in a movie like Pushpak for which I had particular music in mind. I knew where to start the music, where to stop it, and the texture of the music. The control had to be with me. So I thought of roping in someone like Ray who would be able to give a freshness to the music. Being a filmmaker himself, he would understand what I wanted from him. Finally SL Vaidyanathan did the music.

There are music directors who want to ‘talk’ through their work. I don’t agree with that. He can talk through a personal album or a concert. He shouldn’t voice himself through a film. A film belongs to its director. Music is only a part of the film. A music director should talk through the director. Although Pushpak was a movie without any dialogues, sound was an element in it. The ambience sound and music were critical to the story telling.

There are music directors who want to ‘talk’ through their work. I don’t agree with that. He can talk through a personal album or a concert. He shouldn’t voice himself through a film. A film belongs to its director. Music is only a part of the film. A music director should talk through the director. Although Pushpak was a movie without any dialogues, sound was an element in it. The ambience sound and music were critical to the story telling.

Who came up with the ice-knife idea? The kind you see in Sherlock Holmes stories.

It came up during the discussions. Once the movie becomes a cult, many people want to claim credit for it. It is the work of a team, led by a director.

The movie had an interesting cast. Once I saw Amala compering a film event. She was very natural. She had done a movie earlier. She was bad in it because they made her mouth long dialogues which aren’t really her forte. In Pushpak, she has to emote through expressions.

Amala reminds him of one of his favourite actresses, Audrey Hepburn, from Roman Holiday.

Amala reminds him of one of his favourite actresses, Audrey Hepburn, from Roman Holiday.

Similarly Pratap Pothen, who is known for his dark roles, did comic bits in Pushpak.

But the main person whom I am indebted to for Pushpak is its producer Shringar Nagaraj. The story, at first, was narrated to Kamal. He liked the story. I didn’t ask him if he could produce it, and he didn’t come forward to produce it, though he was already a producer. He could have said, “Come on, let’s start the film.” But he didn’t. I approached LV Prasad and a lot of people. They all liked the concept but didn’t want to produce it.

Finally, Shringar Nagaraj, who had been running an international tour company, came on board. I narrated the concept to him and he immediately agreed to do it. This man, who had never produced a movie before, made Pushpak without compromising on the budget. He didn’t produce another movie.

Pushpak came to life not because of an actor, cameraman, or anyone. It’s because of this person.

Is Pushpak a personal film?

Yes. That’s the life I lead. I don’t want to amass wealth. At the same time, I am not a person who romanticises poverty. Money is important, but that is not everything.

What is cinema for you? A medium of entertainment or a way of expressing yourself?

In our country, cinema, like cricket, is a big business. A lot of people have put money in it. Essentially, it is a commercial enterprise. Let’s not confuse business and art. The business of cinema certainly has a social responsibility of not demeaning the art. If society rejects the films that have little art, nothing can go wrong. Unfortunately, our society encourages that. Sometimes, women’s organisations make a little noise against such irresponsible movies. Besides that, nothing major happens to stop this degradation. There must be an abhorrence from the core of the society.

Also, there are people who want to express themselves. Balu Mahendra, towards the end of his life, made a movie that cost very little money. Being a great director he could have made a big-budget film. But he wanted to do the film that appealed to him. What he wanted, came at that price.

Of all the films you’ve made, which film’s failure hurt you the most?

Raja Parvai wasn’t received well. But later, it became a cult. Not all Thiyagaraja kritis are popular. But even the less popular kritis have that essential Thiyagaraja touch to them. All of Shakespeare plays are not popular, but they are, ultimately, Shakespearean plays.

Raja Parvai was too new for that time. After the release of the picture many people said that it was not the hero who is blind but the producer and director (laughs).

Monetary loss happened, I agree. And that’s the only real loss. All those who talk about loss of reputation, image, and self-esteem are wrong. The real pain is for the people who put their money into it. When a film fails, I am more sorry for the producer than for myself.

The violin segment at the beginning of Raja Parvai – did you plan it that way after you listened to Ilaiyaraja’s composition?

Yes, we shot the scene after Raja gave us the music. That was a special piece. Similarly, for the Urvashi-Kamal portion in MMKR, what I had visualised was a slapstick song with 20 widows, led by SN Lakshmi, doing lalala lalala in the background. When Raja gave me “Sundari Neeyum”, I had to rethink. It was a beautiful piece. So we shot a slow-mo romantic piece. It was shot in 48 frames instead of 24 frames.

In the beginning, Satyajit Ray was an inspiration for you.

Initially he was. Like how Ray made Pather Panchali, we made Samskara (1970) in Kannada. It was a cinematic adaptation of a novel by writer UR Ananthamurthy. Through Samskara we introduced Girish Karnad. We shot it outdoors. We had a wonderful cameraman called Tom Cowen from Australia and an editor called Stephen. Like Ray had Ravi Shankar as music director, I had Rajeev Tharanath, a Saroj player. It followed the style of Bicycle Thieves’ neorealism. But soon I realised that this whole concept of neorealist filmmaking becomes meaningless when it doesn’t reach people. People are more important than all the ‘-isms’.

Like Ray, you are an artist and a musician.

Yes. My mother was a violinist. I have composed music for a few films of Rajkumar. An understanding of art and music helps when you are making a movie.

Music is a feeling. It’s not about swaras or ragas. There are many scholars who are well-versed with every raga and swara, but not all of them are sensitive to music. That’s a different thing. For Ghatothkach, I had initially thought of hiring a different music director. But eventually I did the music by myself. The film needed simple music with some gibberish lyrics composed by someone who could think like a child. And I was the only person in the team who could do that (laughs).

It helps that I am a painter, for when I have to decide on the visuals.

Do you understand animation well?

When I was approached to do Son of Aladdin for Pentamedia, I didn’t know what 3D and 2D was. So, for three months, I attended a class at Pentamedia and learned everything. Subsequently, I started teaching them because I had experience in live-action too. At the end of the day animation films are cinema. They too involve scripting, character development, dialogue writing, and visualising the script.

The character of Ghatothkach appealed to me because he is fun. He finds pleasure in simple things like food, unlike most of our purana characters. And the movie portrays an ideal childhood – how the children dance and play with animals with abandon.

After these myriad genres, what do you want to make next?

I want to make a total musical. With everything pre-recorded. Scripting is going on and perhaps by 2017, I will do that.

Are you generally the most cheerful person on the sets?

Absolutely. Ask any actor. However, I am strict when it comes to execution of work.

Did you have any particular rules on the sets?

Yes, when I was doing Magalir Mattum, I asked Kamal Haasan, who was the producer, not to come anywhere near the sets. He obeyed that rule (laughs).

For the three female characters I wanted three actresses who were good friends in real life. Finally we cast Revathy, Urvashi, and Rohini. When we were doing their combination scenes there was so much life in it because they were friends. Later, Kamal remade the film in Hindi. He even played Nagesh’s dead body in it. The film is yet to be released.

Why did you make a film on women?

Once, I was approached to make a film based on a script that revolves around a husband who suspects that his wife is having an extramarital affair. I rejected it. I strongly feel that if a woman chooses to have an extramarital affair, it’s her right. Even today, I stick to that.

People look at me and think I am just an old man with orthodox viewpoints. Have you noticed that it is always a male actor who is featured in advertisements of scooters and cars? And female actors for that of a cooker, washing machine, and detergent powder? So indirectly, male chauvinism is telling women all the time that your job is cooking, cleaning, and running the household. For 60 years, I have been asking my wife to stand up for herself. To not be apologetic about anything. I support anything that rebels against that chauvinism. So I made Magalir Mattum. It is a very funny movie too.

Who is the funniest person you have come across?

I am very funny (deadpan expression). There are people like Nagesh and Rajkumar. I don’t know. I am my favourite. And my second daughter. She is very funny.

Have you ever thought of creating a superhero character?

That’s something on my mind.

What will be his special powers? A killer sense of humour?

He will definitely be funny. But not being normal will worry him. Finally, he’ll find love and start leading a normal life, but then he’ll realise that he has to choose between this newly found happiness and his superhero powers. Because being normal is sucking out his superpowers. My superhero will be caught between responsibility and true happiness.

You once planned to make a movie on Jesus Christ. What happened to that?

Yes. We went to Jerusalem and other Biblical places, hunting for locations. But the movie didn’t take off. (sighs)

The cast was all kids. Pawan Kalyan was supposed to introduce the movie to the audience. And the story would be told through children. However, that recce was unforgettable. We visited places where Christ is supposed to have lived. I am not a religious person, but there, I felt compelled to kneel down and pray.

What is religion to you?

Humanity. Happiness. My wife is very religious. She prays and visits temples. I am not. I pray so that it makes her happy. I believe the mind is a more important element than faith. One should be able to rein in one’s own mind, especially in the film industry, where ego rules the roost.

I’ve been the Chairman of Gollapudi Srinivasan Awards right from its inception. We honour a new filmmaker every year. It’s a great learning experience to watch the brilliant films that come every year to the award committee. I learn from them.

What keeps you going?

I want to do better. The kind of movies that no one has done before. Till today, no one has done a Pushpak or Aditya 369.

What movies inspire you?

KV Reddy’s Bhakta Poddana was the movie that inspired me to make a career in films. I watched the movie as a young boy, and later, I requested him to make me his assistant.

I admire directors like Alfred Hitchcock, David Lean, Akira Kurosawa, and Vittorio De Sica. For me, V Shantaram is the best director India has produced. Not Ray or anyone else. Ray, even when he had a great story in hand, deliberately kept the narration less appealing to ordinary people. His films had a very complex texture. In the West, there are many good realistic films, which won the hearts of the ordinary masses and serious film viewers alike.

There are a lot of good new directors in India – like Anurag Kashyap and Vetrimaaran.

But aren’t their films dark and violent, in fact, the opposite of your films in every way?

I am an avid watcher of the Game of Thrones series! I enjoy those films. Game of Thrones, for one, is a very well-made series. Until some years ago, my wife and I used to attend international films festivals held at different Indian cities regularly. Those films were very realistic, dark, and violent. How violent is a Kashyap movie or Game of Thrones episode compared to some of those Korean/Japanese movies?

He tells me that he is always caught up on the latest TV shows, and has watched the entire season of Narcos already. And before I can even complete my question about his favourite actors, he jumps in.

SV Ranga Rao is my favourite actor and Suchitra Sen is my favourite actress. I have never worked with her. But I have always loved watching her on screen. What a sensitive performer!

*****

Recommended

It’s not easy to write a film in this age. I see bookstores closing down due to poor sales. Youngsters have no time to read. They want quick results. They prefer abridged versions to anything long, deep, and time-consuming. I remember watching 5-day test cricket. And now youngsters have T-20, an abridged version.

Making a film for a society which doesn’t have time for anything is a challenge.

*****

Singeetam’s wife gently reminds us that it’s past lunch time.

She has been with me through thick and thin. It’s not easy to be a filmmaker’s wife. We never leave each other’s company. She travels with me. We discuss everything. We are mutually dependent.

Perhaps this unaffected admittance of emotional and intellectual interdependence best encapsulates this remarkable filmmaker’s work and persona.

*****