Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Haasan Manto were charged for obscenity in their writing. Chughtai for the homoerotic Lihaaf (Quilt) and Manto for Bu (Odour) – the story of a relationship between a prostitute and a man. Both the trials were held at the same time, Chughtai in her essay ‘The Lihaf Trial’ writes that while she was considering to tender an apology to the judge even though the case against her was not strong, Manto could not be persuaded to apologise. During the trial, when the witness said that the writer’s use of the word “chest” to describe a woman’s breasts was offensive, Manto’s reply was, “A woman’s chest must be called breasts and not groundnuts.”

But that was Manto. Nothing sanitised, pristine would work for him. He was the voice of the depraved, the ignored, the marginalised. At the Cannes film festival this year, a film on Chughtai’s Lihaaf was announced and Manto, a biopic by Nandita Das was screened.

#TeamManto having a great time during an interview with IMDb. pic.twitter.com/PnCXQfhA9J

— Manto Film (@mantofilm) May 15, 2018

ये ज़रूरी है की ज़माने की करवटों के साथ अदब भी करवट बदले… #Manto #RedCarpet @Festival_Cannes #UCR #CannesWithManto pic.twitter.com/RpuymQGhah

— Nawazuddin Siddiqui (@Nawazuddin_S) May 15, 2018

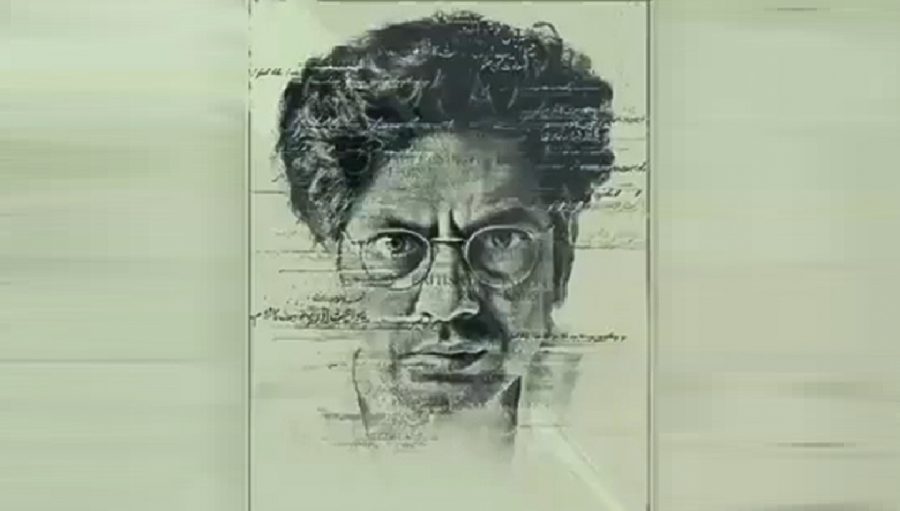

The Hollywood Reporter writes about the film, “Here, the versatile Nawazuddin Siddiqui (he was the cheerful apprentice accountant in The Lunchbox) is transformed into an astounding resemblance of the writer, in what may well be Manto’s definitive screen persona. Siddiqui hurls Manto’s talent, wit, self-destructiveness and tragic gravity at the world like a punch in the stomach — in fact, very much like the stories he was writing after 1946, when the film takes place.”

“Most critics connected with the film, the characters and were immersed in the journey. The praise ranged from calling it the Garm Hawa of our times to ‘handsomely mounted prestige piece’.”, said Nandita Das after the screening.

For Das, the sole purpose behind making the movie was to trigger conversations, to urge people to ask themselves difficult questions and to make them face inconvenient truths.

This is not the first film about the long-lost writer. The 2015 Pakistani film, under the same title directed by and starring Sarmad Khoosat, was subsequently developed into a TV series, packed with short stories. The series talks about the writer, who grew up in the showbiz industry of Bombay (now Mumbai) and Lahore. It throws light on the last seven years of the writer’s life, during which he wrote some of his most controversial stories, including ‘Thanda Gosht’, ‘Toba Tek Singh’, ‘License’, ‘Upar, Neechay aur Darmiyan’ and ‘Peshawar Se Lahore’. For these, Manto had to face charges of obscenity thrice.

Films aside, several plays have also been adapted from Manto’s life and his written works. In fact, Bollywood legends like Pankaj Kapoor have also played Toba Tek Singh. There is also Mantostaan by Rahat Kazmi. It’s based on Manto’s four seminal stories on Partition and displacement. Kazmi will be making a film on Chughtai’s Lihaaf with Tannishtha Chatterjee playing Chughtai and Sonal Sehgal, Namita Lal, Mir Sarwar and Shoib Nikash in the supporting cast.

First look of #Lihaaf [The Quilt] unveiled at #Cannes2018… Directed by Rahat Kazmi… Based on a story by Ismat Chugtai… Stars Tannishtha Chatterjee and Sonal Sehgal… Produced by Rahat Kazmi, Tariq Khan, Zeba Sajid, Namita Lal, Umesh Shukla, Utpal Acharya and Ashish Wagh. pic.twitter.com/dWyQAeDMe2

— taran adarsh (@taran_adarsh) May 16, 2018

Long-lost and forgotten from literacy, Manto was one of the very few writers who wanted to make a living out of writing. However, the immediate aftermath of the post-partition period caused Manto to relocate to Lahore, with much reluctance.

Fate had it and the author vanished from existence during this period. His work was never spoken about and he banished and exiled without a trace. But at some point, upon reaching adolescence, a few girls and boys would one fine day find his work lying around in one corner and read it with trembling hands only to wonder about his clandestine existence.

The stories of Manto are not pretty evening-time entertainment to be ingested with a glass of wine. They are gut-wrenching, nauseating, stomach-churning renditions (all of which created the buzz) of a time when India was split into two.

Recommended

Manto’s is a liberal voice that makes immense sense in these turbulent, polarized times. No wonder Das, introducing the film at its premiere in Cannes, spoke of it as being a response to what has been happening around her. From humanism to freedom of expression, from displacement to Hindu-Muslim unity, Manto ticks all the right boxes without getting righteous, moralistic or pedantic.

Celebrated for his stories of Indian partition, Manto was a distressingly prophetic and daring writer. “Manto’s stories were radical in their own time and they are still radical,” says the author and academic Preti Tanuja.

As for the film, Siddiqui seamlessly transforms as Manto and his handsome face with cleft chin and defiant gaze is mesmeric. The rustic sets of old Bombay and Calcutta make you travel back in time. And when Manto has finally hogged the limelight, will the film do justice to the great writer’s genius? Well, that might remain unanswered.