On October 8, Vijay Sethupathi, a popular actor in the Tamil film industry in India announced that he will play the role of Sri Lankan spin legend Muttiah Muralitharan in an upcoming biopic.

What followed was a barrage of requests from his fans and others in the film fraternity to walk out of the project. What began with requests, swiftly morphed into threats, hate speech and a clarion call to boycott the actor’s film.

From veteran filmmakers in the industry to ministers from the ruling party in Tamil Nadu, everyone issued statements, all of them carefully crafted as ‘warnings’ to this up-and-coming Tamil actor who had agreed to play the role of a ‘betrayer’ of the cause of the Eelam Tamil community.

Makers of the film rushed to assure the public that the film is purely a ‘sports biography’ that will not ‘make any political statement favouring any community’ and ‘will not showcase any scenes that would belittle the struggles of Eelam Tamils in Sri Lanka or hurt their sentiments in any way’.

The backlash however, continued to pour in. Veteran director Bharathiraja on October 15 wrote a second open letter to Vijay Sethupathi in which he asked: “Do you want your face to be looked at with hatred and forever be associated with a man who has betrayed the community?”

Another prominent filmmaker wrote: “This film is not bigger than the people who made you live. Brother..leave it.”

Muralitharan, who comes from the neglected and downtrodden, hill country Tamil community in Sri Lanka broke his silence and issued a statement on October 16. “I know the pain of losses from the war. We had to live in a war-stricken Sri Lanka for more than 30 years. 800 is about how I achieved success after getting a place in the cricket team in the midst of such a situation.”

The Tamil diaspora in India, however, was not convinced.

On October 19, in his last letter regarding the issue, Muralitharan asked Vijay Sethupathi to pull out of the project to avoid facing any consequences. “I have never been tired because of setbacks and have always won, against all odds, to reach where I am today.”

The actor’s publicists, meanwhile, confirmed that he had officially walked out of the project- 12 days after it was officially announced.

Why did the biopic spark a row?

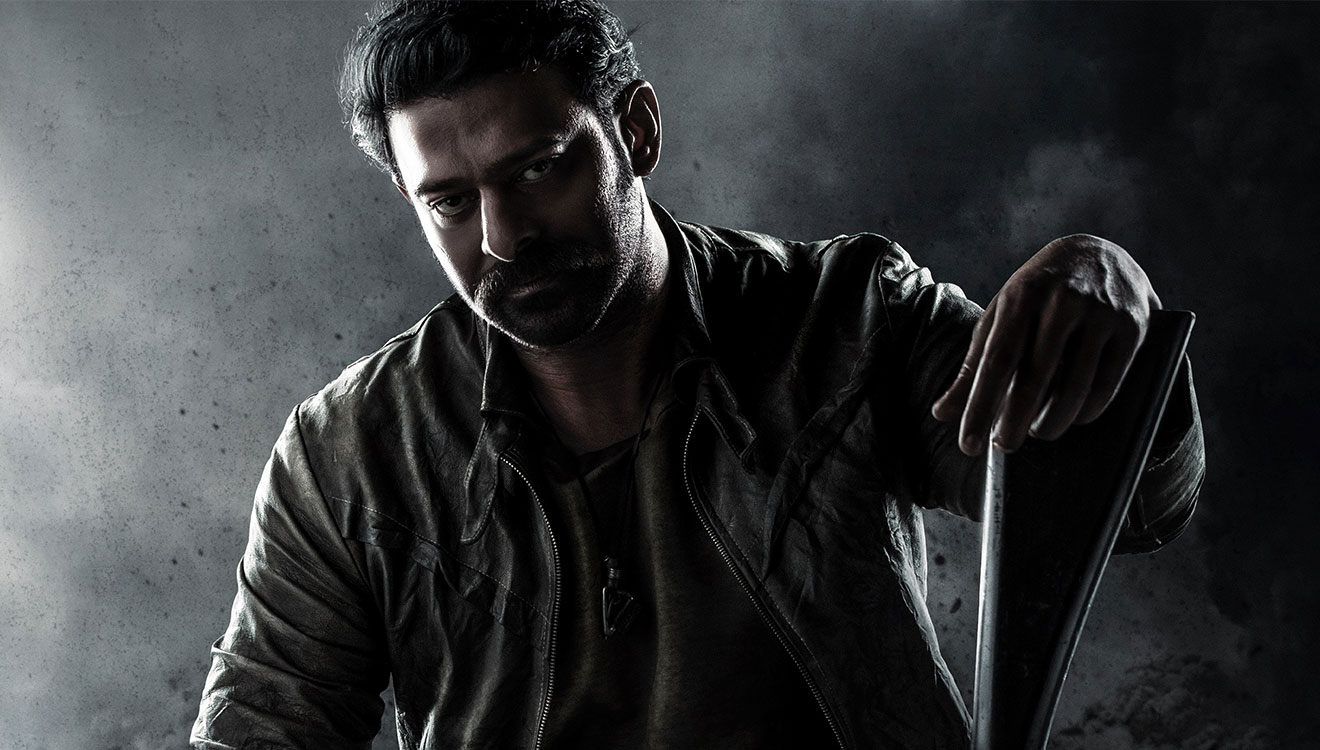

VJS and Muttiah

“This wound is very deep and very raw for Tamils,” says Ramu Manivannan, professor and head of department of politics and public administration, University of Madras; who has collected and submitted evidence on war crimes in Sri Lanka, and represented the cases at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva between 2012 and 2015.

“It’s not about Tamil nationalism- even the cinema world is completely against this renowned, highly respected and well-regarded actor- Vijay Sethupathi – acting as Muttiah Muralitharan for a film. Even if Muralitharan spoke some other language and if a Tamil actor has to do this film, people will still oppose. Because, he has certainly taken stands against the Tamils of Sri Lanka- whether he feels part of them or he is an upcountry Tamil doesn’t matter. You cannot defend a genocide in a civilised world,” says Manivannan.

“More than 1,00,000 people died during the final days of the war and more than 1,40,000 people disappeared. In such a situation, a person of his (Muralitharan’s) repute expressed a position that the happiest day is when the war ended- the war has clearly ended in a way that the Sri Lankan government or the Sinhalese wanted it. He (Muralitharan) also led the British Prime Minister’s visit to Sri Lanka and he was sent presumably by the Sri Lankan government to deny the allegations or issues raised by the Tamils who were talking about people who have disappeared. More than 50,000 young men and women have disappeared! He just stepped in to defend the government’s position. He has also undoubtedly campaigned for the Rajapaksas. Rajapaksa is considered as the man who is responsible for the mass crimes and genocide against Tamils,” Manivannan adds.

The civil war eventually ended in 2009. After more than 25 years of conflict, the civil war came to an end in May 2009. That month, then Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, presently the country’s prime minister, declared that Prabhakaran, the leader of the Tamil Tigers or the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had been killed and formally declared an end to the civil war.

As the social media row over the film unfolded outside Sri Lanka, many pointed to Muralitharan’s close alliance with the ruling Rajapaksa government as proof of the Tamil cricketer being complicit in curbing minority rights. Many also began digging up old interviews of the cricketer. In one of these interviews, he allegedly says 2009 was the greatest year in his life. In his recent statement, Muralitharan said that his words were misconstrued.

He says May-2009 is the greatest day of his life. If genocide of Tamils is that great to him why can't his biopic be released in sinhalese!? pic.twitter.com/Ki0htAbk3h

— MAHENDRAN THANGAVEL (@RAJARAJAN1000) October 14, 2020

Things are however, not so black and white, say others.

Shades of grey

“I think it’s a lot more complex than people are making out at the moment,” says Andrew Fidel Fernando, Sri Lankan correspondent for ESPNcricinfo.

According to Fernando, both Sinhalese as well Tamil nationalists often do not take Muralitharan’s origins – the fact that he comes from the Malayaha community—into account.

Muralitharan’s family was also the victim of an anti-Tamil mob attack in 1977. His father was assaulted and the family’s biscuit factory burnt to ashes.

“Murali is perhaps one of the most high-profile Tamil figures that we have possibly ever had but that doesn’t mean he comes from that community. There’s a problem with asking him to be a champion of the Northern and Eastern Tamil cause when he’s actually from the hill country Tamil community. For example, the Tamil that he speaks is very different from the Tamil spoken in Jaffna or other parts of the island. Those differences kind of get steamrolled,” says Fernando.

Muttiah_Muralitharan

Fernando pointed out that Muralitharan, in the last few months, has made some shocking political moves in the run-up to elections in Sri Lanka.

“I think a lot of people were disappointed, particularly with one press conference he held with a Sri Lankan nationalist politician. That was very shocking to a lot of people, including me. His brother ran in Nuwara – Eliya in the hill country for the Rajapaksa government and he was also on the campaign trail for his brother,” says Fernando.

“Either out of naivete, or perhaps cynicism, or just trying to get along, or not really caring about politics – it’s impossible to know what his intentions have been – he has over the years said and done things which from the Tamil nationalists’ perspective is an outrage and betrays the larger cause of the Tamils. The fact that he endorsed Gotabaya Rajapaksa for president, for not just Tamil nationalists but for most Tamils, that is an outrageous thing to do, given the central role Gotabaya Rajapaksha played in the war, which saw a minimum of tens of thousands, possibly even more, Tamils killed in ways that violated the laws of war in the final months of the war,” says Alan Keenan, senior consultant on Sri Lanka for the International Crisis Group (ICG).

Keenan pointed out that as an upcountry Tamil in a Sinhala-dominated country and playing in a Sinhala-dominated cricket team, Muralitharan must have constantly faced pressure- to prove his loyalty to his country.

“He is seen, quite rightly, as having made certain choices to ally himself with – or at the very least, get along with, not rock any boats, cause any trouble – the Sinhala political establishment, which for decades has denied equal rights of Tamils and over the course of the last 10 or 15 years has grown increasingly hardline and aggressive towards minorities. This is true not just for Tamils, not just North East Tamils and hill country Tamils alike, but Muslims have also suffered enormously in the last five to 10 years from pressure from the government and radical Sinhala Buddhist groups who don’t see them as loyal Sri Lankans,” says Keenan.

Muralitharan’s politics

The hill country or upcountry Tamils, are descendants of Indian labourers, mainly from Tamil Nadu, who were sent to Sri Lanka by the British to work in tea plantations. Till date, the community is considered to be among the most neglected—economically, socially and politically—in Sri Lanka.

In 1948, the Sinhalese nationalist government stripped thousands of upcountry Tamils of citizenship through the Ceylon Citizenship Act.

According to Keenan, there has been a strong undercurrent of discrimination against upcountry Tamils in Sri Lanka—especially from Northern or Jaffna Tamils.

“The strategy adopted by the upcountry Tamil political leadership in the 1960s, 70’s and 80s and beyond has been to align themselves with the government. The idea was that they were trying to fight and win greater benefits and economic opportunities for their population by being part of the government. The head of Ceylon Workers’ Congress or the CWC, the main upcountry Tamil political party, tried to win something for Tamils by being part of the government. That’s kind of an analogous approach that Muralitharan has followed: trying to work within the system, not rocking boats,” says Keenan.

“To his credit, he has used his fame to do a lot of charity work, he has done a lot of good work- not only for his own community but also for other Tamils. But charity is not the same as fighting for your rights from the state. The latter is the approach taken by the Northern and Eastern Tamil leadership, whereas the general approach of the leadership of the upcountry Tamil community was to work within the government and try to win benefits rather than demand rights. They would make deals in exchange for the votes that they would offer Sinhalese parties. They won some gains. But over the last 50 years, the upcountry Tamils, especially plantation workers, are still at the very bottom of Sri Lanka’s society- economically, socially and in terms of other opportunities, job and educational opportunities. So, the strategy of working with the government and trying to win benefits in exchange for your votes- I don’t think overall has been proven to be a very wise strategy,” he adds.

Muttiah_Muralitharan-web-(1)

Muralitharan has, over the years, not really talked about political solutions or power, says Fernando.

“I think Murali is much more focussed and cares more about people’s economic situation rather than the bigger political questions, from what I have seen and heard of him. His focus on raising a lot of the poorer Sri Lankans and he does that very well through his charity work. There’s no grey area on the fact that he has been an absolute champion on the charity front. His politics doesn’t necessary deal with the bigger political questions,” he says.

Can a Muttiah Muralitharan biopic come without the politics?

Speaking about the biopic in a recently issued statement, Muralitharan had said: “I agreed to making a biopic only because I thought that it will serve as an inspiration for future generations and budding cricket players.”

The makers in a statement had said that the film was intended purely as a ‘sports biography’.

Recommended

“Even if it were possible, that film itself would be a political film and what angers a lot of politically engaged Tamils is the idea that there could be a film where you tell his story and you leave out the political moves and statements he has made or the complicated questions about his status as a successful Tamil in a Sinhala-dominated state. By not interrogating, looking into what the compromises were, what the complications were, you’re effectively implying that everything is hunky dory, that everyone loves everyone, and all are equal Sri Lankans and the Tamils are fine. But that is definitely not the case,” says Keenan.

“I would rather see a movie that deals with some of these political things. If you’re going to do a biopic, I don’t think it should just be about cricket. Murali has occupied a very specific place in Sri Lankan politics, largely unwittingly. During his playing days, he largely tried to stay away but found himself thrown in against will at times. I’m much more interested in seeing a movie that deals with that kind of stuff—a little bit of cultural and political context, rather than just cricket,” says Fernando.

With the row that has erupted and the Tamil actor pulling out of the film, the film’s production has been halted and its future now looks uncertain, say makers.