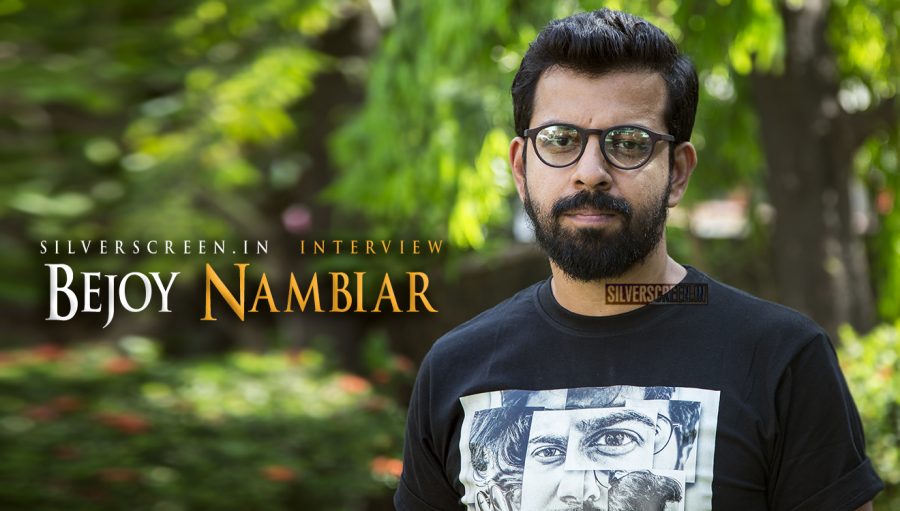

How would a filmmaker, who identifies himself as a Mumbaikar, cater to the growing appetite for rooted films in Kerala? Bejoy Nambiar talks about making Solo, the bilingual featuring Dulquer Salman, growing up with and around movies, and his love for silence.

A late Saturday evening; Sreekar Prasad’s editing studio in Saligramam brims with life. It’s the day after Dulquer Salman’s birthday, when the teaser of Solo was released at a low-key event at LV Prasad Film Academy.

Sreekar Prasad and his team flit in and out of the rooms in the old, one-storeyed building. They are busy; the post-production work of Solo is currently underway, and the editing studio is a hotbed of activity.

This is where I meet Bejoy Nambiar, the man behind Solo.

I’ll never make a bilingual again, he sighs as we sit for a long conversation. “It is exhausting because you do twice the work.”

A moment passes by, and he laughs.

“But, I am sure I will end up making another after such promises.”

Solo is an oxymoronic title for a collection of four stories. Dulquer Salmaan plays the lead in every segment, and Bejoy promises that the film will feature an “entirely different side of Dulquer”.

*****

Bejoy Nambiar is a quintessential Mumbaikar. He grew up in a household of movie-buffs. “Everyone at home loved watching films. VHS library was like my second haven. Naturally, I grew up watching a lot of films, and listening to a lot of music.”

When he was in Bangalore as a student, he worked with the Theatre Club Of Bangalore, for which he directed a play, ‘Getaway’ – also the name of his production house. In 2005, he shot to fame with his first directorial, a short film titled Reflections, with Mohanlal playing the lead role. He also assisted Mani Ratnam in Guru (2007).

In 2008, Bejoy, who was 28, won Sony Pix’s Gateway, a celebrated short-film contest judged by Ashok Amritraj, Rajat Kapoor and Anurag Basu, along with Santosh Sivan. “He truly represents the Indian filmmaker of today with his style and technique,” remarked Amritraj, chairman of Hyde Park Entertainment, an internationally renowned production company. Post the win, Bejoy underwent an eight-week internship with Ashok Amritraj and Hyde Park Entertainment in Los Angeles.

His Hollywood career never took off, but Bejoy announced his entry in Indian cinema in 2011 with Shaitan, a brilliant crime drama centered on a bunch of youngsters, played by fresh faces. One of the producers of the film was Anurag Kashyap. The film won him several awards, including the Screen Award for the most promising debut director.

In 2013, he made his first bilingual, David, a drama, in Hindi and Tamil. The film had an ensemble cast – Vikram, Neil Nitin Mukesh and Jiiva among others. The film tanked at the box-office, and earned mixed reviews. However, its unconventional narrative structure, stylised visuals and great music didn’t go unnoticed. In 2016, Bejoy made Wazir, starring Amitabh Bachchan and Farhan Akhtar. A dark crime thriller, the film was scripted by Vidhu Vinod Chopra.

Solo is his first Malayalam movie, and also, his first anthology. “Shaitan and Wazir had parallel narratives. I think I prefer complex narratives to a simple story. I had done that once, for a telefilm for Zee about a dysfunctional relationship. It’s not yet out,” he says.

But why was Solo made in two languages?

“During one of our meetings, Dulquer said, ‘why don’t we make this film in Tamil, too?’

I liked the idea. If we could cast it correctly, it could work. And Dulquer is a familiar face in Tamil Nadu. If I’d had a chance, I would have tried to make it in Hindi too. It’s just a matter of time before he cracks it in Bollywood. I know many filmmakers in Hindi who are keen to work with Dulquer. I am pretty sure he will be there very soon. If not with anyone else, I will do a film with him there.

The film has an ensemble cast. It must have been quite a task to manage the set.

Every story had its set of cast, and we were doing it in two languages, so some stories had two sets of cast for each language. But I had an excellent team working with me. The production department made sure that things went as smooth as possible.

Are you a good manager?

I have a Masters degree in Business. Something that I’d learned there must have rubbed off here; but at the end, filmmaking is also about managing people. To convince people to follow one vision, and to get them all to help you execute it, requires a certain kind of skill that you acquire over a period of time. The first one might be rough; you learn from the first – in the second, there has to be some progress, not just with managing people, but also to get the work done.

What is the biggest lesson that you’ve learned over the years?

To work with people who are as enthusiastic as you about the project. They should want to work for the film, rather than reasons like money and fame. Also, they must possess the need to do something different – both actors and technicians. They are not doing an easy job.

Is this also because of the fact that sometimes when production gets delayed, and plans go awry, you need people with conviction to stand by you?

Most of the time, production gets delayed. Solo was supposed to be released in June, but it had to be pushed. We have two sets of actors, three different camera men; we were supposed to have four cameramen, but then, there were logistical issues. We couldn’t get the date. So Gireesh (Gangadharan) was sweet enough to step in. All that took time.

Do you rehearse and plan a lot before the shoot?

I am someone who rehearses and does a lot of workshop before the shoot. For all my films, I have tried my best to rehearse as much as possible. Shaitan, I think, was the most rehearsed film of mine. Every scene was planned carefully. That luxury, I have not had for my other films. I don’t believe in the concept of just going [without preparation] to the sets. It really helps me. It gives me an idea of how the actor’s going to do in a scene, so it’s not a surprise. We don’t work without a bound script, and a shooting script. Dialogues, sometimes we improvise [on sets] to make them better.

When scripting, what comes to you first – visuals, or the plot / characterisation?

I don’t know if it’s a bad thing to love good visuals, but it has to go in tandem with the storytelling. The moment it starts to dominate, it’s only about looking at post-cards. There needs to be balance. I look forward to what each person brings to the table. Be it the cameraman or the actors. Although we go with a shooting script, I always wait to see what they can contribute to the film that I haven’t imagined yet. You know, I wait for that magic to happen. It’s not just about clinically executing a written scene, but also to capture that one moment which may or may not be there in the script. I am someone who pushes forever, not just with actors, but with technicians and everyone else. It harks back to what I had been talking about how charged they are about the film we are making.

For instance, during Wazir, it was also about how Sanu [cinematographer] interpreted a scene, how he saw the story happening. I kept giving him a mood board, he took that and internalised it to give me something better. I have been fortunate that whoever has worked with me so far has not only matched my wavelength, but also managed to take it further. I hope that streak continues.

The Thaikkudam Bridge music video, ‘Aarachar’, was shot by Ravi Varman – but it was totally different from the kind of visuals he is known for. The music video is very much a Bejoy Nambiar work.

It was shot in one day. I am a big fan of Ravi sir. I happened to meet him at a party. I told him about this project, and he was enthusiastic about it. We scheduled it for two days, and we finished it in a day. You should see the energy that he brings to the sets. Unimaginable. I am really looking forward to working with him in a feature project sometime down the line. In fact, we worked together in Kaatru Veliyidai, and became close. That energy was channeled into the visuals, I think. I am very happy about the way it turned out. We were trying to up the bar for we thought no one was creating good music videos. We wanted to create a benchmark. Also, I wanted to work with Thaikkudam. The other music video by Thaikkudam in the Navarasa series, One – I was so envious when I saw it. It was shot and directed by Littil Swayamp. It’s a phenomenal music video. I thought I had done something great, but this one was mind-blowing. You should check it out sometime.

The sound department in your films is special.

I work a lot on sound. Even then, I feel it’s not enough. During David, I remember, on the day of the release, we were trying to refine the sound more for the prints that were going somewhere else. I never feel it’s enough. I try to make it better and better. Because, it’s one department that’s generally neglected. In Mollywood, I hear, they get a week or so to do the sound part of the film – I can never do that. That’s one department I am very obsessive about.

Where does this particular obsession, or rather fascination, with sound stem from?

Many a time, while writing, I keep a sound cue in mind. I write with music cues. I have music in my head, and I want to shoot scenes on that rhythm. When I do that, only 20% of the job is about planning and shooting a scene, and 80% work is in the sound part. They [sound engineers] have to design the sound according to how you want it. That will consume a lot of time. Some scenes will require a certain kind of sound design. So each film has its own challenges. I enjoy the process very much.

I have noticed that you make great use of silence, too.

I am a big fan of silence. In fact, my first short film had no dialogue. I like a lot of moments in films, in general, when things are communicated in silence, and as the audience, you are supposed to understand. I like that kind of narrative a lot. Somewhere, it creeps into my storytelling, too. Shaitan had a husband and wife who never spoke; in David, there was a deaf and mute girl Vikram’s character fell in love with; Neil’s character barely spoke, too. Also, just before Neil’s character is shot, there is a big question that he asks his mentor, and there is no answer. It’s silence. In Wazir, there are moments of silence that we played on. In Solo too, there are such portions. There is one big element of silence that I have used. Let’s hope people receive it well.

Our commercial films aren’t really used to silence.

Yes, unless we push the envelope. You hammer it until people say stop doing it. It’s just that. We keep trying. I am not worried about failing. As I said, there is a particular element in Solo, written with silence in mind. The story revolves around that. It’s something novel, and I was anxious to know how the first person I narrate the script to would react to it. Luckily, the reaction was very positive. Then I narrated it to a couple of other people, they liked it too. Then I narrated it to Dulquer, and he was the most excited about it. You really need that kind of encouragement to try new things. For me, it has worked beautifully in the film.

There are filmmakers who say it’s important to not use multiple composers in a film, for that might ruin its consistency. You have used 11 music directors in Solo.

This works for me. In David, there were eight music directors. I use them because I liked their music and I felt the story can take that kind of sound. While writing the script, I start collecting music. I know this song is going to be played here, in this portion. Of course, when you put [everything] together, you will need more, and then, I go around shopping for songs.

You worked with two huge stars – Mohanlal and Jackie Shroff – in two short films, Reflections and Soap. The latter had Shroff in an entirely novel avatar. Reflections has an unconventional narrative. How did you convince these stars to act in the films?

I am lucky that way. That’s all I can say (laughs). Shroff was part of the Sony show. All of us had to pitch him a story, and he picked mine. We had a blast shooting it. He was very excited to play the role of a brooding man who sees his future on a television.

Incidentally, both short films feature middle-aged men feeling insecure about their lives.

They are just stories that excited me at that point of time. Soap was supposed to be a feature. It worked well as a short. In a longer format, it might not have worked.

I made one more short film, Rahu, a 40-minute Malayalam film which isn’t out yet. That’s not about middle-aged men. That was the last short that I made.

When Reflections came out, Kerala was raving about this Mohanlal film, but it is possible that not many people understood what it really meant.

(Laughs) It was very ambiguous. You could interpret it the way you wanted to. That was the idea. It was my first attempt at doing something. I had no idea how to put the visuals together, although I knew this was the story – a man re-imagining his life as he is sitting and watching people at a restaurant. That was the one-line idea.

I narrated it to Mohanlal as such. The whole hook was that you get to know that only in the middle of the film. The initial part is invested in domestic moments – a family of three in a car. When the family walks into a restaurant, everything changes.

What was Mohanlal’s response when he watched the final output?

I will never forget what he said when I showed him the film the first time. I came to Chennai to play the film for him. In the restaurant scene, you see the character smoking. He asked me if he was smoking up, and making up stuff? I said no, he was not (laughs).

You come from a theatre background. How did the transition happen?

My heart was always in cinema. Theatre and cinema are miles apart, but theatre makes one understand actors much more. In theatre, acting happens on a gut level. It helps you judge the actors’ performances. It is a great platform for any actor to start his/her career with. I wanted to understand how the medium worked. When I was in Bangalore, I noticed an advertisement that said Bangalore Theatre Club was looking for actors. My friend and I went for the audition without reading the ad properly. They were looking for only female artistes. We didn’t get the job, but we joined the place as volunteers. The people who run the theatre club, Abhijeet and Poile Sengupta, they are my mentors. They guided me to the world of theatre. I worked with them on their plays, and over the years when I wrote a play, they helped me put it together.

What was your first play about?

The play was called ‘Getaway’, after which I named my production company. It was about three old men who rob a bank, and how it goes wrong. We had a blast. Getaway was the first feature film script that I wrote. It didn’t get made. Prakash Belawadi, who is a rockstar in Bangalore theatre circle, and now a big Bollywood star, was one of the protagonists in Getaway. He did a role in Wazir, and in Solo, he is doing an important role. I think the theatre connection I had is still going very strong. I am aching to go back and do one more play sometime in the future.

Your films have received mixed reviews.

Yes, average to low responses. David almost got no response.

How do you handle failures?

I handle it by aiming for the next, working hard for the next. I don’t waste time waiting and wondering why my film didn’t work. As long as I get to do my next the way I want to make it, I am okay.

Isn’t it difficult to stay afloat in Bollywood without a big blockbuster?

It is difficult everywhere. Even a 100 crore film director will say it is difficult.

*****

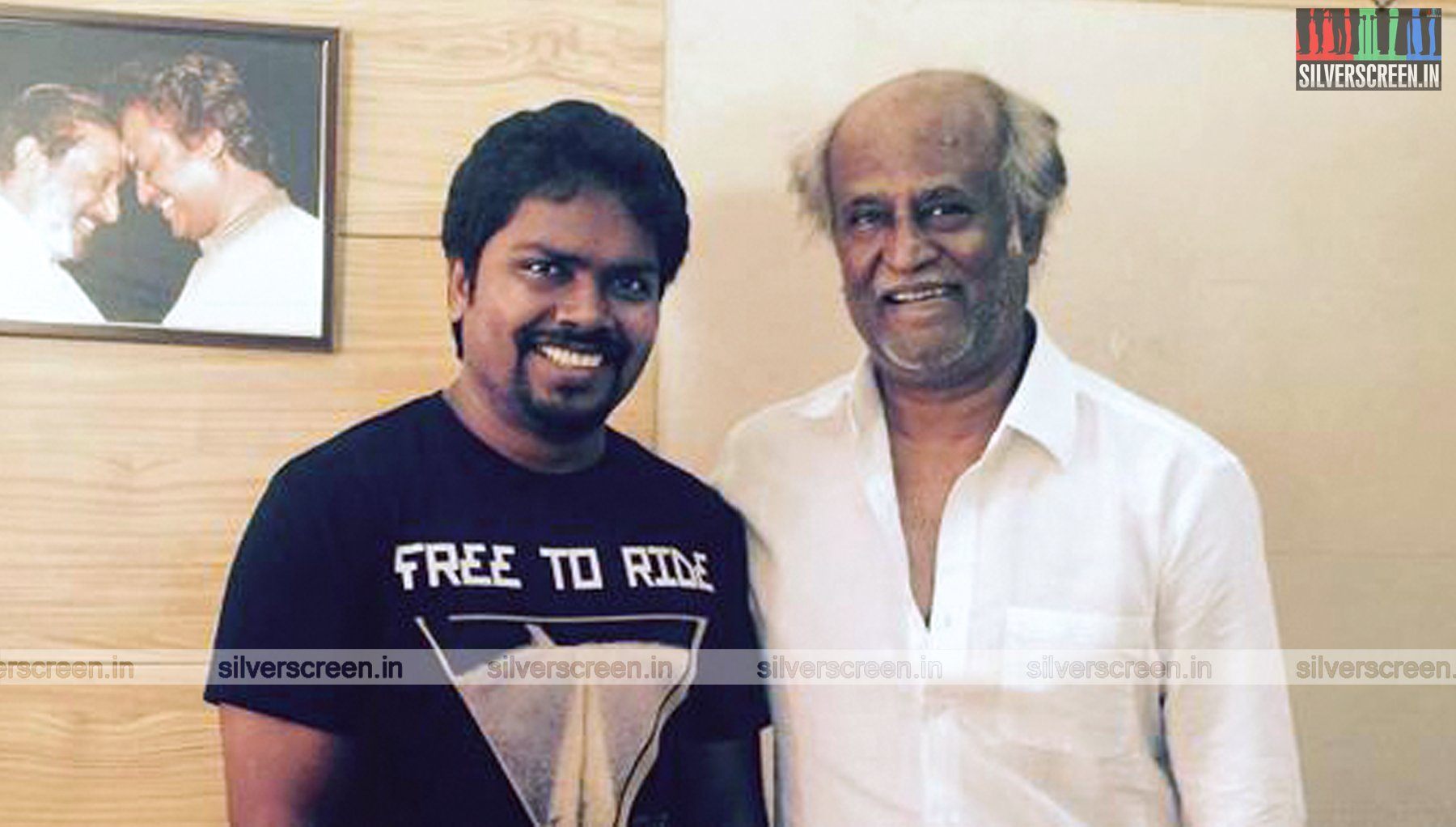

Before the release of Shaitan, in 2011, Bejoy hosted a private screening of the film in Chennai for his mentor, Mani Ratnam, whom he’d assisted in two films, Guru and Raavan. Such is Bejoy’s love and respect for the veteran filmmaker that he went back to assist him in his latest film, Kaatru Veliyidai. Mani Ratnam was the chief guest at the teaser launch of Solo.

Before the release of Shaitan, in 2011, Bejoy hosted a private screening of the film in Chennai for his mentor, Mani Ratnam, whom he’d assisted in two films, Guru and Raavan. Such is Bejoy’s love and respect for the veteran filmmaker that he went back to assist him in his latest film, Kaatru Veliyidai. Mani Ratnam was the chief guest at the teaser launch of Solo.

You were an assistant director to Mani Ratnam. What is the most important lesson that you learned from him?

I am still an assistant director to Mani Ratnam. I am constantly learning from him. That’s the reason I went back to work with him; that’s the reason I will go back to work with him again. It doesn’t matter even if my films aren’t like his. I guess my whole approach to cinema is very close to what he does. I subscribe to his kind of [film] framework a lot. Over the years, I’ve watched all his films, so some time or the other, it creeps in. In Soap, you see Jackie Shroff watching television, and it is Mani Ratnam’s films that are playing on the TV.

You wanted to remake Agninatchathiram?

Yes. It is his most masala film ever. One of his most commercially successful films. I like the film, and also, I feel a fresh take on it will work well. It was way hip for that era. Personally, trying to adapt a Mani Ratnam film is a huge, very huge challenge. Then of course, it was a movie that was far ahead of the time when it was released. To remake it is a challenge. I don’t even know whether I will be doing it. I am focusing on Solo right now. At one point, I was very enthusiastic about doing it, was very close to making it. But it didn’t fall in place.

Being a person who has worked in the non-feature film industry, what is your take on the big debate about Netflix?

It is not like I am dying to work with them, depends on if there is a story worth saying in that shorter format. You have to find synergies, people who are enthusiastic about such a shorter format. I don’t want to get pulled into that debate. All I know is, I too go back home and binge on Netflix. I must say there are some excellent pieces of work there. We are spoilt for choice. If I get an opportunity to do something on that level, why not?

Would you make short films again?

At present, there is no revenue model for short films. Digital platforms are slowly figuring something out. There is a short film idea that I have been toying with for some time now. I will make that film someday.

Has it become easier to find producers now?

With every project, you think it will be easier now, but it’s always a struggle. I am a Mumbai guy. I consider myself very much a part of Bollywood. I don’t know if I belong to the club or not. Now, as I am doing films in Malayalam and Tamil, I try to get to that level.

Malayalam film industry, at the moment, is fond of movies that are very rooted. Being a person who isn’t familiar with the Malayalee way of life, how do you hope to get it right?

It is such an interesting time in Kerala. Very rooted stories, and the audience is accepting them. It is almost like there is a revival of sorts, a renaissance of good stories, and people are taking it. There is a surge in good content and young people are attempting novel stuff. Otherwise, there was a phase, a very strange time in Malayalam, when they were just aping Telugu and Tamil cinema. Now it’s like they are going back and starting afresh.

Let’s see how they respond to Solo. It’s not a typical Malayalam film, although it has a typical Malayalam hero who has got a target audience – the youth. I am pretty confident that the stories that I am trying to say will find resonance with them.

Do you follow the censor board issues that Indian cinema is grappling with at the moment?

That is a never-ending issue. As long as the government is silent, as long as they are not talking or taking this seriously, this issue will go on.

What are the movies that excite you?

I don’t have a favourite genre. Recently, I watched Dunkirk. I had read some mixed reviews, so I went in expecting not to like it much, but I ended up being so impressed. I loved Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum. Fahadh (Faasil) was phenomenal. Dileesh is a director to watch out for. The first film for any director is special, and in Dileesh’s case, it was phenomenal. I loved it so much and I still think Maheshinte Prathikaaram is better than Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum. And, the second movie is always the one that gives a sense of the director’s real potential. That is what Dileesh proved with Thondimuthal. It is such a clutter-breaker. Not a regular film at all. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

I have been hearing a lot of friends in Mumbai saying that they don’t get to watch southern films. There are random shows. So I wanted to create a platform through which they can get to know where these Tamil/Malayalam films are playing in the city. We started it with Angamaly Diaries, and then did films like Jigarthanda. We are soon going to do Thondimuthal.

It’s high time regional cinema breaks barriers, and gets audiences from across all languages. Angamaly Diaries, for one, deserves to be watched, for it’s really great.

Recommended

Prashant (Pillai) and I are friends from long ago. Lijo and I were on that short film show. That’s where both of us started. We have stuck together since then. We keep bouncing off our work to each other. Rather than colleagues and contemporaries, we are friends. I don’t have any friends in the industry, so these are the people I hold on to.

Who are some of your favourite directors?

Many filmmakers. In Malayalam, I love the films of Bharathan, Padmarajan and Sathyan Anthikkad, among others. Then, there are films of Balu Mahendra, and of many directors in Tamil. In Bollywood, Mukul Anand is an all-time favourite. I keep watching his films. I love films of Manmohan Desai, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and of course, Sai Paranjpe. Once on Twitter, there was a question – ‘which filmmaker’s universe would you like to live in?’ – for me, it would be Sai Paranjpe’s.

*****

The Bejoy Nambiar interview is a Silverscreen exclusive. It was originally published on August 9.