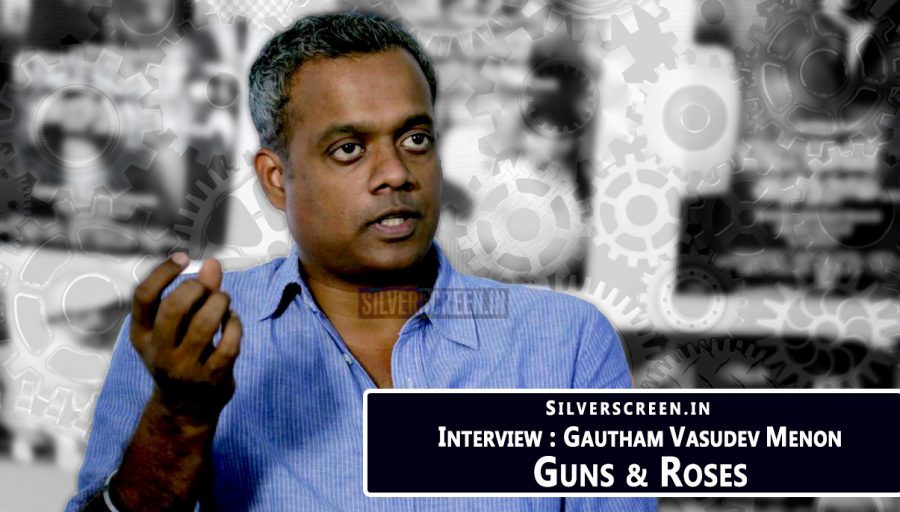

A posh, bustling café in a quiet corner of the city. An occasional hoot of laughter, animated chatter. The clink of a ceramic mug striking glass. A man walks in. There’s a pause in the air, followed by excited whispering. Gautham Vasudev Menon (GVM) smiles easily at the gawking eyes that follow him as he makes his way to our table. He sits down. We talk.

*****

Born in 1973, Gautham Menon stepped into film industry as an assistant to film maker Rajiv Menon in Minsaarakkanavu. In 2001, he made his first movie, Minnale, and so far, he has written and directed nine Tamil movies, and directed Hindi and Telugu remakes of two of his movies. Menon has also produced nine movies. Two of his films, Vaaranam Aayiram (2008) and Thanga Meengal (2013), have won National Awards.

*****

Every young movie fan in South India, metro or small town, admires this man’s unique style of storytelling. I remark, “Some people call you an elitist film maker. That your films are just about people who speak English and visit high-end cafés”. He laughs, “Then perhaps I’m the only guy who makes films like that. I have no problem being called elitist. I generally try and recreate something I’ve seen in life. Or the kind of stories I want people to see.”

Do you enjoy watching the new-generation films, which are very unlike your style of film making?

GVM: “I can’t relate to new-generation films that glorify violence. I like older directors and their films. There will be bad guys in my films and there will be a hero who takes them on. I won’t glorify violence in my films. If there’s violence, there will be a hero who comes and tells you: this isn’t the way.”

Your next film Acham Enbathu Madamaiyada also explores this everyday cinematic violence.

GVM: “It’s a love story. A story of friendship. It’s a story about bikes, about being on a road trip and just wanting that wind on your face. Violence and action in films makes it look so easy. But when you actually face a situation where somebody is throwing a punch at you, and you have to defend yourself or protect somebody, how would you react? Do you have it in you? That’s what this film is about. It deconstructs all the violence you might have seen on screen, and says: all that is just for film. This is the real thing.”

*****

His debut film, Minnale, was candy-floss young romance. But now, his oeuvre has some of the most celebrated modern-day love stories in Tamil cinema. He has a unique directorial style. His characters are urban, classy and display emotional vulnerability at some point in the film, regardless of who they are. His men aren’t shy to cry. I tell him this, and Gautham Menon smiles, “Most of my characters have some of my traits.”

Of all your characters, is there one you’re emotionally attached to?

GVM: “There are many such characters. I like Karthik from Vinnai Thaandi Varuvaaya a lot. He is a trier. When somebody you really love walks away from you, you are left with so much of pain. Even in that situation, he is able to channelize his pain to write a story, and make a film. And it becomes a stepping stone for him to reach somewhere in life. If these characters were real, Karthik would have been my friend. I would have been telling him, ‘don’t do this, don’t do that’, ‘why did you do this why did you do that’.

“I also like Surya’s characterisation in Vaaranam Aayiram, a partially autobiographical film. I like the dad’s bit because these are the characters I have seen in life. I liked even Kamal sir’s character in Vettaiyaadu Vilayaadu because he readily accepts the woman even though she is going through a bad marriage and is divorced. These are qualities that come naturally to me, which is why I like these characters.

“Among the female characters, I would choose Nitya from NTEPV, Maya from Kaakha Kaakha, and even Hemanika from Yennai Arindhaal.”

You’ve said before that the college scenes in your films are partially autobiographical.

GVM: “My college was in Trichy. I met a lot of people there. Earlier, I was restricted to 3-4 friends in school and my sisters and mother and father. College opens people up. The first day, I didn’t like it at all. I had never been away from my house. I had never stayed outside alone. When I looked around, I saw 3-4 guys. There was a guy from Kerala, a guy from Bombay, one from Chennai. We connected instantly. Even now, they’re my friends. I think college life streamlines you. It’s essential for everybody to experience [life in] college.”

Most of your films are set in Chennai. What does this city mean to you?

GVM: “I have lived my whole life in this city. I was born here. I studied here. My dad, a Malayali, also studied in Chennai, at the Madras Christian College. We have always been die-hard Chennai people.

If I am outside the city for 4-5 days, I miss Chennai.

“Its home. When I am working in another industry, in just 10-15 days, I am itching to come back.

“In school, I studied Hindi, never Tamil. Though I was born and raised in Chennai, I am just half-Tamilian. But somewhere I wanted that connect with the language. When I went to Trichy, I interacted with a lot of Tamil speaking guys and my knowledge of the language really improved. I started picking up books. I have not really tackled Tamil literature, but I know the stories. I think in English. But when I am writing for a film, I don’t think in English. I am making a Tamil film, so I think only in Tamil.”

*****

All his films, even the police trilogy, had romantic tracks. The most memorable part of Yennai Arindhaal, in fact, was Ajith’s relationship with Trisha’s Hemanika.

Has your way of approaching romance on screen changed over the years?

GVM: “What you feel for somebody stays the same. How you feel for her or him is the same. How you approach that and how you take it forward is probably what is different these days. But I don’t see any change in the way I direct a love story. I work a lot on characterisation. Take Nithya in Nee Thaane En Ponvasantham. She is very independent. But, when it comes to love, she would give up anything for a boy she’s besotted with. When she finds out that he’s going abroad, she’s angry that he didn’t tell her. His viewpoint is different. He feels it’s what he wants to do; why should she change what she wants to do for his sake? These are things two normal people would go through. I just put myself in their place. I don’t think love has changed at all. I look [for inspiration] at old films like Pyaasa and Shree 420. Not the new love stories.”

What are some of your favourite old love stories?

GVM: “Shree 420, the film with Raj Kapoor and Nargis. Aawara, with the same pair. Also, some of Kamal sir’s films like Satya. Even Thevarmagan, where a love story does not go forward because of circumstances. These are my reference points. Maybe a modern-day love story like in Agnikashatram between Prabhu and Amala, an independent girl.”

*****

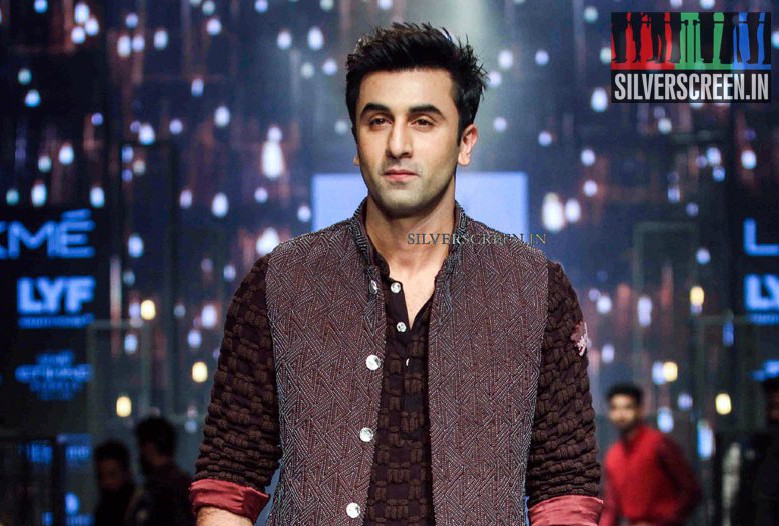

Acham Enbathu Madamaiyada is Menon’s second collaboration with STR, after Vinnathaandi Varuvaaya, one of the most discussed modern romantic dramas in Tamil.

Did you write the script with Simbu in mind?

GVM: “No. Actually, after the first half of the script was written, I narrated it to a couple of other heroes. When the Suriya project got shelved, I met Simbu and told him that I have this script. He said he liked it, and we decided to take it forward. Then I made some changes to suit Simbu.

“Normally I don’t write scripts keeping an actor in mind. I write it the way I watch a film on screen – without actually knowing who the hero is. I think of it from an audience’s point of view. I write the scenes, the screenplay and the dialogues, and then I put all the actors in.

Some of his films had big stars in it – Kamal Haasan (Vettaiyaadu Vilayaadu), Ajith (Yennai Arindhaal), and Suriya (Kaakha Kaakha, Vaaranam Aayiram).

Did you face commercial pressures? Did you have to alter the script to suit their image?

GVM: “Yes. That comes in once you bring the actor on board. But thankfully, I have been lucky enough to work with people like Kamal sir and Ajith, who never insisted on anything [excessively] commercial. As long as it worked for the script, they were okay.”

*****

Menon’s panache for music is well-known. He rendered the old Hindi songs that Suriya’s character sings in Vaaranam Aayiram. In Ne Thaane En Pon Vasantham, he sang the title track, originally Ilaiyaraja’s composition. Recently, a video of him singing ‘Aanandayazhai’ from Thangameengal was uploaded on YouTube.

Would you consider playback singing or composing in the future?

GVM: “I like to sing. I don’t know or care if I’m a good singer. I think I always wanted to be a musician. I wanted to play. I wanted to compose music. I’m doing it, though I haven’t put anything officially out. I want to play guitar and drums. I have tried learning, but somewhere I have not cracked it. And I feel until I do, I don’t want to put myself out in public. I make films because I am really confident about my films. With music and singing I am not really confident so I haven’t really come out and done it.”

How do you figure out the best lyrics for the songs in your films?

GVM: “Most songs are script-based, so I send out the first draft to the lyricist, telling them this is what I want. I put out an English version because that is part of the script. Thamarai or Muthu Kumar. It’s mostly Thamarai with the love songs. She will convert my idea into lyrics. She wouldn’t translate it as it is, but she takes the ideas and gives it her own words.”

People say that Thamarai’s best work is in GVM’s films.

GVM: “If I tell people that we can go with someone else, they say ‘No no no, you and Thamarai. It’s a great combination, let’s not upset that.’ There is something that she comes up with that is different.

I won’t call it poetry, or prose. It’s like a sense of life.

“I can’t describe it better than that. Of the songs that she’s written, ‘Anal mele panithuli’ from Vaaranam Aayiram is my favourite. I also liked the recent ‘Unakenna venum sollu’ too.”

*****

Gautham Menon has appeared in blink-and-miss roles in his own films. The side-seat bus passenger in the ‘Kaadhal Koncham’ song in Pachai Kili, the police officer in Yennai Arindhaal, the background dancer in Vettaiyaadu. He will also act in Mollywood director Vineeth Srinivasan’s Nivin Pauly-starring Jacobinte Swarga Rajyam.

Tell us about your acting career.

GVM: “My acting career happened because sometimes there wasn’t anyone available to do that particular part. See, at some point, I might I become an actor. Earlier, I would have said absolutely not.

But these days, I look at most actors and I think, ‘hey you know what, I can do a better job!’

“It’s just that confidence. If a big director or a good director asked me, I might just do it.

“I love cinema. I can probably compose music, I can write. I could probably be a cricket coach, or I could just while away my time at home. But this, cinema, is a passion. I am driven by films. I think film all the time. I want to create and put something on the screen all the time.

“I don’t think I can ever retire from films and film making. Ideally everybody talks about reaching a certain point and then completely stepping away. I would probably produce and get more people involved in the craft. I won’t just retire.”

You’ve already started producing films.

GVM: “I want to get people on board and help directors get their scripts across. I really want to fund more films. Naduneesi Naaykal was an experimental film. From the beginning, we knew it was going to be an experimental film. Thangameengal, I really liked it when I heard the story. It was arty and a classy kind of a film. We knew it was going to have a restricted viewership, but somewhere I think audiences are ready to watch such films. Thangameengal, I don’t know if I can make something like that. I don’t relate to the kind of people you see in that film. I would fund scripts that I would normally not write. I just look at it from an audience point of view and see if it moves me.”

How did you handle the failure of ?

GVM: “With every film, I hope to connect with the audience, and sometimes it’s disappointing [when they don’t]. But I never let that bog me down. The real problems are the other issues – when money isn’t easily available, when producers don’t understand you, and court cases which you need to fight. Other than that, when films don’t work, you move on. I think failure really helps streamline you and condition you. I am not saying you need flops. But I am saying it’s good to be in a bit of an up-and-down situation in life.”

Have you ever faced serious writer’s block ? How do you handle it?

GVM: “All the time. With every film. I distract myself by not writing at all. I travel. The block can go on for a week, or 10-15 days. I never force myself to write when I’m stuck. It wouldn’t come out well. It’s like you just had a break up and on the rebound, you go after somebody. That’s not going to work at all. I never push myself to write. If it doesn’t happen, I let it go. I watch films, read books, listen to music. And then the thoughts just open up.”

What’s the toughest part of filmmaking?

GVM: “Writing. Once you get the writing done, you can get anybody on board. Directing is also tough because there are a lot of other things going on. What funds are available, which actors are available, managing time, what to shoot. Finally when you get to shoot, how to take that particular shot, how to get that effect. You have to be adept with the technique, your cameraman has to be in sync, everybody around you has to be in sync. That’s a huge job in itself.

“And you have manage stress levels. There are moments when things won’t be available to you. There’s the time factor. You have to worry about light. The cameraman suddenly says it’s 4 pm and there’s no light. Then you have to immediately adjust things.”

It sounds like a huge task. Do you ever lose your cool on the sets?

GVM: “So far no. I think I’m a good manager. People around me tell me I am. Usually work happens automatically without me having to lose my cool.

“Even when I was working with giants like Kamal Haasan, I think I could hold my own against them. I am not saying it with any ego. I have high expectations from people like him. So when I narrate a scene or a dialogue, I hope he gives it something else. And always, he does. So I’m just happy that I am in that place. As long as I manage to get what I want with something that [actors like him] give me, it’s a nice combination for both.”

One last question. What’s your take on censorship?

Recommended

GVM: “I don’t believe that things are going well, and I feel something should be done about it. It’s not about placing a tagline saying ‘No Smoking and No Drinking’. People aren’t that naïve, to be misled by somebody smoking on screen. They know it’s not a style statement any more. What these guys should be looking out for is the content. At whether the kids can view it or not.

“Vettaiyaadu Vilayaadu had a U/A certificate. The producer wanted a U certificate, but I felt we could go for a U/A certificate. Sometimes people get away with it. Vinnaithaandi Varuvaaya was given a U/A because they said the love in the film was too intense for a child to understand. I found that strange.”

Note: The interview had stated the release date of Minnale as 2002, instead of 2001. We sincerely regret the error.

*****