On October 24, Twitter was abuzz with #ArrestPrakashJha tweets. The film producer and director’s web series Aashram’s upcoming season was touted to be ‘Hinduphobic’ and it wasn’t long before Twitter users began calling for his arrest. The backlash against Aashram comes at a time where many filmmakers have been forced to withdraw their content due to mounting pressure from social media.

Brands like Eros Now and Tanishq were not only coerced into withdrawing their advertisements, but were also forced to issue apologies.

Earlier this month, when the second season of Amazon Prime Video’s show Mirzapur was announced, #BoycottMirzapur2 started trending because series actor Ali Fazal had voiced his opinions against the Citizenship Amendment Act. Similarly, cricketer Muttiah Muralidharan’s biopic 800 drew severe criticism and backlash on Twitter, forcing actor Vijay Sethupathi to step down from portraying the role of the cricketer.

“The political opinion of an actor has nothing to do with the artistic merit of the film or show. In a creation of a film, the actor is only one entity; there are so many other professionals who are involved,” says Abhineet Gogne, head of the department, writing and direction, FX School.

நன்றி.. வணக்கம் 🙏🏻 pic.twitter.com/PMCPBDEgAC

— VijaySethupathi (@VijaySethuOffl) October 19, 2020

Speaking on the trend of using Twitter as a platform to get filmmakers and creators to rescind their works, film critic and scholar Parichay Patra says: “It seems like an extremely dangerous trend that may inspire similar consumer behaviour on several other occasions in near future. It needs introspection and exploration.”

A movie is not just a piece of art, it invariably conveys a message. Protests against works of art could happen for several reasons. While it may not be possible for some to view films merely as a work of art, it can offend a section of people in society. Movies like Dam 999 were banned because of the fear that it may cause unrest due to the film’s political tones.

“There is an obvious rise in the culture of intolerance. Moreover, it has been normalised and legitimised. Films cannot be seen as mere art objects, they always have their politics embedded in the conditions of production and exhibition, in their aesthetic choices, narratives, their ways of addressing the audience and the cinema institution,” says Patra.

Accused of hurting religious sentiments, movies such as Vishwaroopam (2013) and Madras Cafe (2013) were either banned or released after several cuts.

“That is a grey area. If you look at art in the West, the criticism of Christianity is rampant in all forms of art even in music genres, such as heavy metal,” says Gogne.

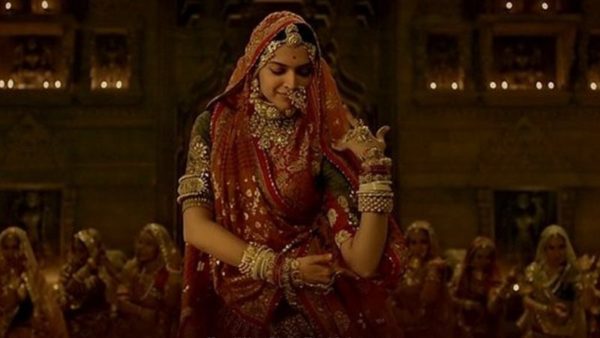

Movies such as Bombay, OMG- Oh My God!, and Padmaavat faced severe backlash for hurting the religious sentiments of the people. When Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) released in 1996, an angry mob claimed that the movie was an insult to Indian culture and traditions for depicting two sisters-in-law engaging in a same-sex relationship.

The type of protests that films have faced earlier is very different from the protests that are prevalent on social media, say film experts.

“The Fire controversy has been able to generate significant academic responses. However, these protests were not backed by the state back then, they anticipated what was about to come. The political culture in the subcontinent has undergone many transformations since then,” says Patra.

Citing the example of Mani Ratnam’s 2002 film Kannathil Muthamittal, film studies professor Uma Vangal says: “There were mild protests from child adoption agencies because of the way the topic was portrayed. But this type of viciousness was not there.”

Leveraging social media to discuss art is always a double-edged sword. Experts feel that while it allows movie makers to create a buzz around their films, it also spreads hate. Explaining that protests on social media have become a fad, maker of the film Dust Udita Bhargava says: “It takes no effort. You do not have to gather anywhere and it becomes easy to create, spread, and voice their opinions.”

Earlier, the film industry was considered unreachable. Thanks to the internet, that gap has now narrowed considerably, bringing them within easy reach of their audiences. This has also helped social media users to mobilise support, enabling them to target and troll film personalities.

Recommended

Film scholars, however, believe that this type of backlash will not necessarily hamper the kind of content that creators are making. Filmmakers might engage in self-censorship but that is not likely to be permanent. “If an ad or film is pulled out, it is not because the makers do not believe in what they are doing but they understand that now may not be the right time to do it,” says Vangal.

While filmmakers and critics feel that social media’s influence is undeniable and partisan in nature, it might not be easy for them to work without taking backlash and criticism into consideration. While it is not impossible, it will be difficult to do so.

“Fake accounts and their political activities will surely remain a point of concern. But popular cinema always finds its own ways of responding to and dealing with such mechanisms. I think it will continue with that,” concludes Patra.