Perhaps the biggest success of director Ram’s Peranbu, which released a fortnight ago to great critical and commercial acclaim, is that it has got people to speak about a section of children whose lives are swept under the carpet in pop culture and public discourse. It has also initiated discussion about trans people and the incredible love one of them showers on Peranbu‘s Amudhavan and Paapa. It has also taught us that it is pointless to ponder about why four follows three while counting stars, because stars can’t really be counted. Why did Ram choose to shoot his film thus, in a way where it slowly seeps in and then triggers questions?

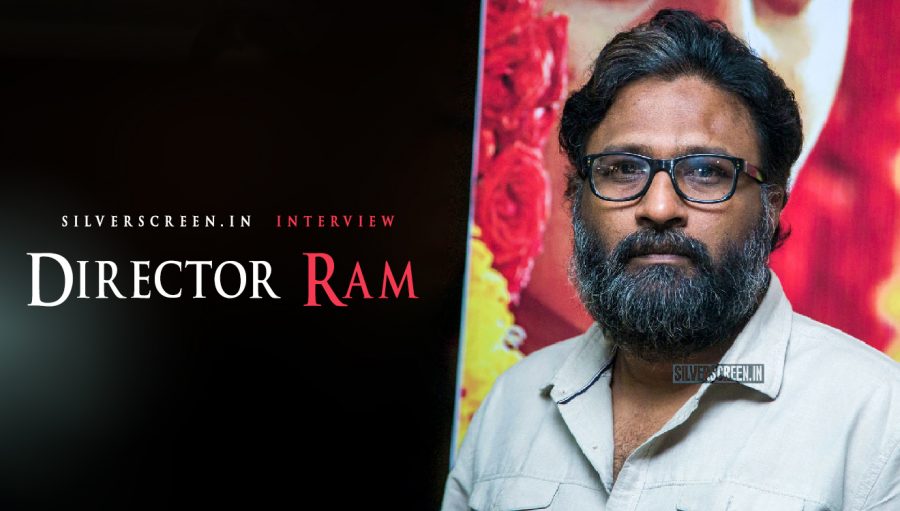

It’s 00.45 hours and director Ram is at the check-in counter at the international airport in Chennai. He’s just got in from Hampi and has to board a flight for Qatar, where his much-feted Peranbu is due for release the next day. I wait on line as he excuses himself for two minutes. I hear the lady at the counter ask him for his full name, the reason for the journey and details of his visa. “My film is releasing,” says Ram, with joy in his voice, and adds, “It’s called Peranbu”. “You’re from Kerala? It stars your Mammuka,” he says. The lady’s excitement filters through the line. “You directed Thangameenkal,” pips in another. And, the two-minute break becomes five. In another 10 minutes, he’s at immigration. There, he says hello to an official who knows him thanks to frequent trips, chats with him about life in general, and ribs him that he’s not watched his film yet. In the vastness of the airport, he resides in his own small world. These few minutes of conversation are enough to place Ram in context. He has been a man of the masses, remains one, and has no plans to change anytime soon.

Much like his films, which revel in the intimate, even when set in the backdrop of something as magnificent as Nature. Peranbu, his most successful film commercially, falls in the same genre. Nature is the nurturer and also the one that hurts and looks cruel, but it is also the healer.

Excerpts from an interview in which we try to decipher Ram’s storytelling technique and filmmaking ideology.

Your films are deeply intimate and seem to showcase the home as world philosophy, including in Peranbu. But, it’s not really easy to keep films small. Where does your film language come from?

I’m a student of literature and I learnt filmmaking and found my film language and techniques through literature, primarily in Tamil. My platform is the Tholkaapiyam, the ancient Tamil treatise on grammar and poetics; it helped me understand art and art quality, and as you start to read literature, you go deep into a character, sociologically and psychologically. When you understand a character both internally and externally, instances, sequences and scenes flow smoothly. When you’re doing a film for the mainstream audience, you should strike a balance to establish that connect. Till now, I’ve managed to make films with limited characters that go into the heart and mind of the characters, and place them in a sociological time. If you notice, there is no antagonist or protagonist in my movies; most often, time is the antagonist.

What gives you the courage to walk on the path you’ve chosen?

I think I’m stupid and crazy and I blindly believe that people will accept whatever I give them. That’s a gut feeling, and I’ll make movies till I have that. I have immense faith in my audience, for they have supported me from day one and given me confidence. Sometimes, it might not click in the short term, but it lasts; Katradhu Tamizh was not a hit if you look at the Friday it released, but it was a hit for the last decade. That people still remember a film that even I don’t remember gives me great pleasure and courage.

I also believe that art has to trigger debate, it should encourage people to come out and speak. That happens with my films; I like that my audience has to come out and talk after watching them, they can love me or hate me, but cannot merely walk away. Luckily, I make films in Tamil Nadu, which I believe is the best place to experiment. They celebrate and appreciate you, probably not economically, but in some other fashion.

There’s also a hint of the surreal in your creations… there’s a certain purity in everyone, something not often seen.

Every film of mine plays out a thesis. My characters debate or dictate my thesis. I use characters as a tool to communicate my thesis to the audience, discuss it with them.

I don’t believe in character arcs, because my movies are not about characters or a single person’s life. Secondly, I’ve seen people who live like my characters; not one of them has a character arc. Nobody in real life has a character arc; your character is fixed based on certain things — time and place of birth, the society you were born into, the school you went to. Having said that, it does not mean you follow it all your life. Everyone has another side. But, I also believe that nothing is real, life is not real. I live in nostalgia. I sometimes feel I and my characters are hypocrites. They question themselves, have guilt, anger… they don’t celebrate or appreciate anyone, they are humble, they feel they can’t keep pace with society or its rules. Thirdly, I can’t create something from air; everything is here already. I’ve met an Amudhavan in real life, I’ve met women who handle their special children. What I showcase is hardly 2-3 per cent of real life. But, it looks surreal because my characters are like the ‘extras’ in a film; I also think in life, the maximum people are ‘extras’.

Your films manage to put across the most radical of thoughts in a narrative that’s quite traditional…be it Amudhavan heading out to find a way to satisfy Paapa’s sexual urges, his keeping away from the room when he sees Paapa having a private moment with the television on or seeing Paapa paint breasts on a doll using nail-polish…

That last scene signifies the development of the child, she’s coming of age, but she does not know how to express it. And so, she paints something she’s seen on herself on a doll. As for Amudhavan, he goes around looking for a male sex worker, because he is not able to understand or handle what his daughter is going through. Once he decides to end their lives, he decides to fulfill her wishes, be it her desire to wear a uniform or her sexual urges; that’s all his exposure is. He is confused, and does not have the clarity or vision. I have come across parents who deal with these issues in their everyday life. And, I tried to reflect their heart and mind when I wrote this. I feel the Government should run sex health services for the disabled as they do in countries such as the Netherlands.

There, the Government has authorised the disabled to use their grant/subsidies for sexual services 12 times a year. Many might wonder why the Government should get involved in this. But, this is about providing solutions to health issues and promoting the rights of people whose presence is often ignored by the community. Aside from the pleasure, sex is considered a form of physical and mental therapy, and has the ability to fulfill the needs of self-esteem, validation and intimacy. We don’t want a world where it’s easier for the disabled to visit sex workers; I want a world that sees them as sexual beings and prospective partners.

What goes into the creation of characters that are flawed and yet full of grace? Of characters that put dignity above all else…

The people I’ve met in life were not perfect. They’ve done good, but they’ve also committed small mistakes and are sorry for it. Our minds are controlled by Nature, seasons and climate. At the end of the day, every human being wants another. I think we are unfit biologically to live alone. We survive better as a unit. And, for that, we need people to be graceful in victory and defeat.

Was Amudhavan, for all his flaws, a thaayumaanavan (the father who also became a mother)?

He can nurture, but he can never become the mother. He can’t replace Thangam (later Stella). She is the greater person; for 13 years, braving the taunts of the family, she single-handedly taught Paapa everything. Amudhavan learns on the job, but I won’t say he’s a great dad. If he were, Paapa would have had a mother, the story might have been different.

In one scene, Stella’s new husband tells Amudhavan in passing that their new baby is “normal”. Was that an intentional line to let Amudhavan know that it’s only his child who is special?

He mentions it in passing, he’s not vicious, he just wants to ensure Amudhavan leaves the house. But yes, there’s always the angle of genetics.

As a director, you share close bonds with your actors. You work repeatedly with Anjali and Sadhana…

I speak to Sadhana like an adult. Even during Thangameenkal, I never treated her like a child. I gave her responsibility to complete a shot. I would tell her what would happen if we did not finish shooting a scene, and I felt she could handle that as an artiste. With Anjali, it’s a teacher-student bond, Katradhu Tamizh was the first film for both of us. Mammuka is a master in acting. I love him a lot, I take the liberty of tousling his hair, he’s someone I’ve admired for long. With some people, you forge a bond as naturally as you breathe; not because you are good or they are good, but because it’s meant to be. I still call Anjali Anandhi (her KT character) and Sadhana as Thangameenkal’s Chellamma.

A director such as you needs a producer who understands your filmmaking. How lucky have you been so far?

Very. I am still friendly with all my producers. The thing is, I tell them the story, I’m very frank with them when it comes to the budget and possible box office success. I tell them how I intend positioning the film. In the teaser and trailer, I let people know what genre of film they are going to watch. I introduce the rhythm and tone of the film. There will be a connecting point that decides whether the audience will want to watch it or not. For my kind of films and the tight budget I choose to work in, I can’t do regular branding. And so, I creatively use all available ‘free’ avenues. My focus is on break-even. Profit comes next.

It helps I don’t believe in classifying markets by age group. I think if a film is made with a certain genuineness, anyone can watch it and be convinced. Peranbu is the first film of mine to be released in more than 450 theatres in India and abroad.

There’s a lot of visual literature in your scenes.

That comes from my love for poetry. It’s full of metaphors. I feel every shot is a metaphor, because the film is a simile by itself. We use a sense of light, time and space to create meaning. That process excites me.

Is Peranbu your most honest film?

I don’t think so. I keep trying to make an honest film. In this film, I learnt to be very simple in the writing and filmmaking. That way, it was honest. But, I think Thangameenkal was the most honest because I think I wrote it from what I’ve been through in life. I’ve experienced that bond.

Will you ever make a happy film?

It’s easy for me to make films like the ones I do. Yes, I like to experiment with genres, but it depends on the zone I’m in. I might make a totally stupid film as my fifth, also a genre by itself, but I want it to trigger debate. I never plan, because you never know what life deals you. I never thought Peranbu would receive this kind of love.

Your films are very structured, even while they are fluid. Your locations are built into the story. How do you storyboard? And, what is the visualisation process like?

What do you think is visualisation? Setting the tone and mood of the film? I don’t think that is the director’s job. A commercial film requires storyboarding; since I don’t make them, I don’t storyboard either. My idea of visualisation is not what is in my head, or on screen. It is that the director has to ensure that every scene bears the film’s philosophy and also reflects the nature of the scene. Time and space, as it were. A scene is not about two people talking. They talk that way because of the place they are in, the weather that prevails. If the weather changes, their conversation will too. Kodaikanal is a place, but I’ve made that my space. You can visit the place where the bungalow is, but it won’t give you the same meaning Peranbu did, because for you it’s a place; in the film, it’s a space.

What is your take on the emotional violence the children you write go through? Be it Chellamma being ridiculed in school for getting her ‘M’ and ‘W’ wrong or what Paapa goes through in the home she’s sent to.

I’ve also been a child, and my children are living childhood now. The parents consider them children, but for the world, they are growing beings. Like it or not, knowingly or unknowingly, there is always a sliver of emotional violence against children. The percentage changes, that’s all. In fact, our lifestyle itself is emotional violence — the rich-poor battle, for instance. Emotional violence can take place without someone wanting to hurt the other, and children learn their way around the world through this. They learn soon enough that the only way out is to grow out of childhood.

Chellamma, Paapa… any Bharathiar connection?

No, I’ve always said I name characters after people I like. My sister’s name is Paapa. Chellamma and Vadivu are my grandmothers. Anandhi is the name of my friend from my Tirupur school, Amudhavan my co-director, Thangam is the female protagonist of Jayankanthan’s Unnai Pol Uruvan, Babu is the protagonist of Mogamul, Viji is Moondram Pirai’s Sridevi, Tharamani’s Prabhunath is my assistant director’s name and KT’s Prabhakar is my professor’s name…

What is your take on the infantilisation of the disabled? Was it a conscious attempt to lend Paapa agency by allowing her to express her likes and dislikes?

Recommended

I’m yet to read about this theory. I won’t generalise this, because it depends on the IQ level of every kid. There are a lot of differences among special children, and all parents need children to be independent; it’s the greatest gift to give them. Many mothers have not been away from their children for even a day.

Peranbu has allowed many to soul-search. What did it do to you?

It gives me a lot of courage and compassion, questions me a lot. After making the film, I can understand someone’s anger, blame and pain from their perspective. It taught me that the biggest thing we seek in life is peace, amaidhi. That’s what is most important.

*****

The Director Ram interview is a Silverscreen exclusive.