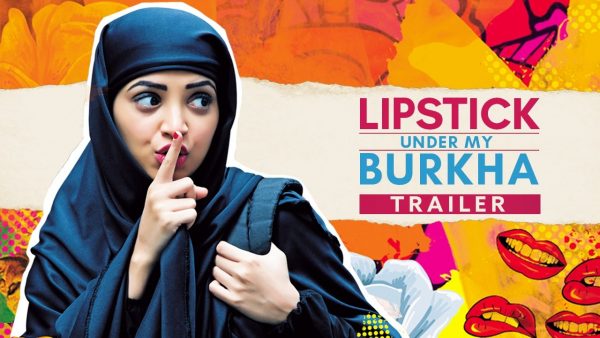

The second trailer of Alankrita Shrivastava’s Lipstick Under My Burkha is underlined with a mischievous sense of humour. Quoting newspaper headlines that refer to the six-month long battle the film had to wage against the country’s Censor Board, the film advertises itself as “The Most Controversial Film Of The Year”. The trailer uses the now-famous phrase that the Censor Board used to mark its objections against the film – “A Woman’s Fantasy Above Life”.

It is as though the Censor Board gave Alankrita lemons, and she used them to make a luscious lemon cheese cake. Lipstick Under My Burkha, Alankrita’s second feature film, releases in theatres on July 21. She spoke to Silverscreen in between promotional events.

“My first film {Turning 30!!, 2011} was given an A certificate. But, at least, it got a certificate without my having to run around for it. This time, they refused to give one altogether,” says Alankrita. She applied for a censor certificate in December 2016, and it was finally issued on June 3, after the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) overruled the CBFC ruling. The whole episode was exhausting, she says.

“It shouldn’t take six months for any filmmaker to get a censor certificate for his/her film. Here, it was not just a scene or a word, but an entire film waiting to get cleared,” she explains. “And, it was a difficult film to make. Ever since I started it, I have had, like, no life.”

Lipstick Under My Burkha is about the secret life of four women from lower middle class households. “I wanted to explore the turmoil within the women, as well as the external restrictions imposed upon them by society. If Turning 30!! was set in a world I was familiar with, this is different.”

Alankrita admits that she is more a literary person than a cinephile. “My two favourite Indian films are Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi and Monsoon Wedding,” she says, and starts listing her favourite authors. “Elena Ferrante, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath…” The filmmaker grew up in a progressive household and studied at some of the best educational institutes in the country – Lady Shri Ram College in New Delhi and Jamia Millia Islamia, where she did Mass Communication.

“There were no external restrictions in the world where I grew up, but, many a time, I did feel many internal restrictions.” The film, though, is set in a world where the women are bound by strong external and internal restrictions.

The four lead characters in the film are played by Konkona Sen Sharma, Ratna Pathak Shah, Plabita Borthakur and Aahana Kumra.

The four lead characters in the film are played by Konkona Sen Sharma, Ratna Pathak Shah, Plabita Borthakur and Aahana Kumra.

“The characters are partly fictional. I didn’t go and meet any particular person, but I adapted a little from the journeys of women I have met in real life. Sometimes, I’d meet a person and think, ‘Oh my God, she is so similar to the character I am developing’,” says Alankrita.

She narrates an interaction with her former landlady. “She was always quiet and meek. I never had to talk to her about anything because it was her husband who handled the rent and other things. One day, she called me up and said she wanted to have a chat. She came up to my place, and we had so much to talk about. I was really taken aback, because I had never thought of her that way. It is the way society conditions us. We slot people in boxes, ” she says.

Lipstick Under My Burqa features women fighting the ways of society, and trying to live out their ambitions. The film does not cater to the male gaze that popular culture is used to. The trailer hints that the film has sex scenes, which according to Ratna Pathak Shah, will make the audience uneasy. “It is a disturbing film for women as well to accept the fact that, yes, we do use sex, sometimes. Here are our various relationships with sex…,” Shah had said in a recent interview.

While the film was grappling with the censor controversy in India, it was having a dream run at film festivals abroad. It was screened at 31 film festivals; in April, at the International Film Festival of Los Angeles, the film was chosen as one of the official Hollywood Foreign Press Association Screening entries, making it eligible for the next Golden Globe Awards.

“Luckily, we applied for a censor certificate after the film had started travelling to international film festivals. That kind of offset the dark period. Even as the film was struggling to get censored here, it was receiving appreciation and love from so many countries,” says Alankrita. “If that had not happened, the whole episode would have really upset me. I found that, at a deeper level, there was something universal about the film. The audience from different countries and cultures could relate to it, and embrace the tale of the women,” she adds. “And, I think men could really understand what we were talking about. So, it is transcending a cultural context. That gave me a lot of strength and validation.”

The director knew from the beginning that she wanted Konkona Sen Sharma and Ratna Pathak Shah in her film. She credits her casting directors Shruti Mahajan and Parag Mehta, who conducted rigorous auditions, with finding the rest of the cast. Cinematographer Akshay Singh is her long-time collaborator – they worked together on her first short film, documentary, and feature film.

The team, comprising veteran actors and freshers, did a lot of rehearsals and workshops before the final shoot. “A lot of stuff got ironed out during those sessions. It helped us bond. We were clear what we were going to shoot. We knew the back stories of the characters. That eventually helped set the tone for their performances,” says Alankrita.

The team, comprising veteran actors and freshers, did a lot of rehearsals and workshops before the final shoot. “A lot of stuff got ironed out during those sessions. It helped us bond. We were clear what we were going to shoot. We knew the back stories of the characters. That eventually helped set the tone for their performances,” says Alankrita.

Shah plays a grey-haired widow in the film, a role quite unlike the stereotypes of familial characters or the ‘seductress next-door’ roles that popular culture has assigned to women of her age. “Whatever women in our films and in real life are made to do is what men like to see them do. We have been watching cinema through the eyes of men for a long time, and even women are used to it. The feminist point of view is scarcely represented in our culture. Are women really happy being confined to the roles men have assigned them? Of course not. Women are normal human beings with all the ambitions and passions others have. You cannot deny it.”

She feels that the poor representation of female filmmakers in Bollywood is one of the reasons for the male-centric stories the industry churns out. “We should be at least 50%, while the real number is meagre,” she says. “This is an uncertain, emotionally taxing job. This is a very dynastic film industry. It is not easy. A lot of women filmmakers come from a film family or camp.”

Alankrita feels there is a dearth of female narratives in Bollywood. “The big-budget films are hero-centric. There are some scripts by indie writers and filmmakers that are not being made into films, because there is no one to fund them. We have an economic system that does not encourage the independent film industry,” she says.

“Independent filmmakers here make films fighting against all odds. They have to do so much to just exist. The system isn’t giving any support. There is no public funding or a supportive distribution system. It is very difficult to get a big studio to fund your small movie. Then, there is the casting process. You can’t afford any stars, which makes distributing the film even more difficult. You can’t compete with a big movie for an exhibition space or splurge money on marketing. How will a Masaan compete with a Bajrangi Bhaijaan?” she asks. “You get an audience when you promote your films, and here you don’t even have money to get distributors. Everywhere, you are at a disadvantage, and you have censorship on top of that. The fact that these films exist is a miracle. This tribe of independent films should win bravery medals. It is a very daring job.”

Studios splurge money on a tent-pole film when they can take out some of it and make a small film, she says. The audience culture is not encouraging too, she adds. “The situation could really change if the audience embraces small-budget independent films.”

Recommended

It is not wise to think of film festivals as saviours of indie films, Alankrita opines. “In my case, film festivals gave a lot of support. But, not all independent films work in the festival circuit. They could be unique, not-very-commercial films with a style that might not work at an international film festival abroad. For such films, you can’t expect that your film will travel to all festivals, because it might not necessarily cater to their idea of what an Indian film has to be.”

The way out is to develop an economic system that enables independent films to be financially sustainable, she affirms. “There is no running away from the fact that the audience in India needs to engage with independent cinema if a parallel narrative has to exist. That will boost the confidence of studios too.”

Pic: miamifilmfestival.com

*****

The Alankrita Shrivastava interview is a Silverscreen exclusive.