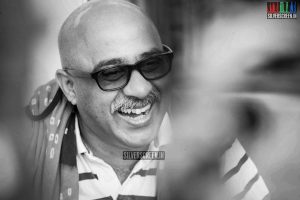

Muraleeedharan-C-K-s

He makes his way through the gathering and disappears behind the elevators.

A few minutes later, we meet at the coffee bar and start talking. His love for cinema shines through our entire conversation. The medium has changed his life forever, and it continues to influence him as a person even now.

*****

Born and brought up in rural Kerala, CK Murladheeran is one of the most accomplished cinematographers in India. Beneath the gentle demanour is the immensely skilled man who brought to screen two of India’s highest grossing films: PK (2014) and 3 Idiots (2009). A close collaborator of Bollywood filmmakers Rajkumar Hirani and Sriram Raghavan, Murladheeran’s oeuvre includes hundreds of documentaries and short films; and dark-thrillers like Ek Hasina Thi and Johnny Gaddar alongside light-hearted films like Lage Raho Munnabhai.

He has just finished shooting for Ashutosh Gowarikar’s period drama Mohenjo Daro, a film he describes as one of the most challenging of his career and his first Malayalam feature film, Rosshan Andrew’s thriller School Bus, in which his teenage son plays one of the leads.

*****

Sipping on a coffee, he starts taking about the Kerala he grew up in. “Those were peculiar times”, he begins. “The late 70s and early 80s. The Left movement was active, but the Naxalites had suffered setbacks. There were a lot of frustrated youth in Kerala hoping for a change.”

Art flourished amidst the unrest. “There were a lot of people translating international literature to Malayalam. I remember reading Marquez in Malayalam before he was translated into any other language. In that atmosphere, it was hard not to get drawn into literature. I used to read a lot.”

He continues about how he learnt about cinema by reading. “Cinema was the in-thing then because it was a new medium. I would read a lot about Indian and international cinema, though I never got much opportunity to watch the movies. I came to know about European cinema and India’s new wave of directors like Shyam Benegal and Satyajit Ray from reading about them in periodicals.”

His eyes light up at these memories. The old-fashioned noble romanticism of the times.

“You could write to the publishers and they would send books through the post office. I remember getting a set of books by mail that I hadn’t paid for. They came with a note saying I could pay them later. I wrote back to them thanking them for the trust they had in me. I still remember the reply they sent to me. ‘What’s life without being able to trust people?’”

*****

Muraleedharan holds fond memories of his days at the Pune-based Film And Television Institute of India, his alma mater. “I landed in Pune without knowing any English or Hindi. For a person from a very middle-class background who grew up in a town in interior Kerala, Pune was a big cultural shock. Meeting students from all over India and other countries. Different cultures. Different languages. Different politics. It was something different altogether.”

The first movie he saw at FTII was Polish filmmaker Andrej Wajda’s acclaimed Man of Marble. The film took him by surprise. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” he says. “Could films be made this way too? (After seeing this) I was confused whether I should continue to like the films of resident masters like Balachandra Menon.”

The films he saw at the institute helped mature his world-view. “Cinema has the ability to mature one as a person,” he tells me. “To understand how elements like politics and nudity are handled in other parts of the world. To see how people from Germany or Argentina look at love and relationships. To learn how Chaplin created humour from his own life.” He soon realised that cinema was “something deeper and heavier than he had assumed before.”

At FTII, Muraleedharan lived and breathed cinema. “We’d discuss Russian Communism, politics, art, life and everything under the Sun. There was very little money, but there was cinema to feed on. Every moment you are talking about cinema. Every joke you crack is about a film. It was a different world altogether”.

*****

And that is why he feels that the ongoing controversies over freedom of expression at Jawaharlal Nehru University and FTII are “pathetic.” “I am a part of the FTII strike,” he says, adding, “I support the students from outside. I am for freedom and free-thinking. Universities are a space for debate. Such debates sharpen one’s point of view. This has to be protected. No one should try to curtail that freedom.”

He is pragmatic about the impact of films on society. “I don’t think that films can change society. They are a reflection of society. If we are living in a society that suppresses voices, you will start seeing suppressed kind of films. It is filmmakers’ responsibility to reflect the society honestly. But,” he adds, “I can’t say I have been a part of such (honest) films all the time.”

*****

After he graduated from FTII, Muraleedharan’s life was “Struggle. Lots of it,” he says. “I did not have a place to stay in Mumbai. I’ve slept on footpaths and been thrown out of friends houses where I overstayed my welcome. I kept trying to find a job so that I could find food from somewhere.”

He pauses before continuing. “Sometime back, I was travelling through Pune with Sriram (Raghavan) in a car. He asked me why I never went back to Kerala after I graduated. I hate big cities, but I still came back to Bombay after graduating. And I stayed back. Years later, I still hate cities. But I’m used to this now.”

*****

Rajkumar-Hirani-&-C-K

And soon after, he started his stint in television dramas, through friends like Rajkumar Hirani. It was the Doordarshan era of Indian television, dominated by independent producers willing to experiment. Or as Muraleedharan puts it, “The Saas-Bahu trend hadn’t started yet. Channels were producing content-backed programming; and everyone was experimenting with the medium. I worked on episodes in which one shot went on for 12 – 13 minutes. Three such shots made one full episode. The industry was brimming with energy.”

When the era ended, so did Muraleedharan’s involvement in television. “In the late eighties, when the Saas-Bahu soaps started coming in, I quit television and started doing films.”

*****

He had an inauspicious entry into films with Shashilal K Nair’s controversial Ek Choti Si Love Story. “I didn’t get along with him very well,” Muraleedharan says cryptically, and moves on to happier topics, about his long association with Rajkumar Hirani and Sriram Raghavan, that includes Lage Raho Munna Bhai, 3 Idiots, Johnny Gaddar, Agent Vinod and PK.

1G7U1705

Both Raghavan and Hirani narrate their scripts to him even before they are fully written, and he is involved in their films from the very beginning. “I’d read PK‘s script as early as 2012. If I am not able to connect to the story, I tell them that. Johnny Gaddar, for example. When it was narrated to me I told Sriram that I didn’t like it. But later, it went on to become a great film.”

But the involvement took a toll on his ability to sign more projects, and he is consciously stepping back. “I used to enjoy that level of involvement in movies. But, nowadays, I step back a little. It consumes a lot of time, and I am never able to take up other projects. But,” he adds, “I always insist on getting a narration from the director before I read the script. I am a director’s cameraman.”

*****

CK-and-Sriram-Raghavan—Agent-Vinod

Raghavan is unconventional, and Muraleedharan says, “believes in not planning. Strongly.” He adds, “I share a wonderful relationship with him. He lets what happens on a particular day dictate terms. We discuss everything extensively, and the whole process is thoroughly enjoyable.”

*****

Muraleedharan does not like to be called a technician. “I am good at technology. I am a physics graduate, and I like science and technology. But ultimately I am an artist, a creative person. I think and work like an artist. But in the industry, we are always called technicians. I hate being called that. I don’t go to the location with a set of spanners. I go with my head. I am an artiste who uses technology.”

And with that out of his system, he starts talking about how he keeps up with technology. “I read a lot. I talk to people from the industry. And I experiment. I try to do things differently to see how technology can be used.” He illustrates with examples. “Sometime back, I was shooting a rain sequence in Rajasthan when the temperature was nearly 49 degrees Celsius. We were filming a rain sequence. When you try to protect the camera from water by covering it, the camera stopped working because it was too hot. So I made a case for the camera with fans inside.”

“And similarly, I had use a hundred thousand diyas (lamps) for a song sequence in MohenJo Daro. And I ensured that the set was fireproof before we shot the sequence.”

*****

Ashutosh Gowariker’s historical Mohenjo Daro is, Muraleedharan says, “my most challenging film. It’s not easy to make big-budget movies totally realistic. Not all large-scale Bollywood movies can be called modern cinema. But I didn’t want Mohenjo Daro to be that kind of cinema. It is set in prehistoric times. The visuals have to match the audiences’ idea about that era. Designing the lighting structure was challenging. I did the (indoor)lighting, mostly, from ground, and not from top because those days, there were no electric lamps. People used diyas that were kept at an arm’s reach. I had to design a new kind of light for certain effects. It was a challenge to light up the underground caves and tombs. It took a lot of research. I consulted pictures of old shrines and buildings from Indus Valley era to get the effect right.”

He praises Gowariker for his meticulous research on the project. “He wanted everything to be foolproof. Archaeologists from India and abroad were brought to the sets, and were made to walk through it, giving suggestions. We would have lengthy discussions all the time, on every aspect. He has been with me throughout the course of the movie. One of the best collaborations I ever had.”

*****

1G7U9632

The long delay in signing his first Malayalam film was because he had no time, Muraleedharan says. “When I left Kerala for Pune, I had plans to come back and work in Malayalam industry in the future. But whenever Malayalam film makers call me for work, I would be engaged in a Bollywood movie, which consumes a lot of time. Thus that delay happened. Rosshan (director of School Bus) has been calling me for the last 5 years. This time when he called me, I had just finished Ashutosh’s film.”

He praises regional cinema in India for having found its own style finally. “They are making amazing films in Kerala. Even the Marathi industry is doing really well. For many years, regional cinema was in Bollywood’s shadow. Especially Marathi cinema. They’ve found their language, and have progressed in how well they make films. Malayalam filmmakers, for example, cannot make big-budget movies, so they experiment with themes.”

*****

But he is scathing in his assessment of Indian cinema as a whole. “We don’t make films,” he starts off. “We shoot radio plays. Our cinema is an extension of theatre. We write a script and dialogues, and then we use visuals to show the actor saying the dialogue. (Beyond that) visuals have little role to play in our cinema. When we say it is a good movie, we mean that we liked the story.” He pauses to smile. “ I like Sriram’s films, but I can’t say more. I’m part of this industry.”

He does have some advice for filmmakers: Take risks. “We’re bound by fear. Directors are scared of trying different things. If someone makes a successful film in a particular genre, he’ll repeat the genre throughout his life,” he says. “Look at the James Bond franchise,” he adds, “each movie is made by a different director, and they all are so different.”

*****

Muraleedharan maintains a blog where he writes about cinematography and cinema in general. Ask him about it, and he says he loves writing, and wishes he had more time to write. “I hope, after this movie, I’ll get some time off to write on my blog.” He laments that the contributions of technicians in Indian cinema are not preserved well enough. “Thanks to PK Nair, we have an archive for Indian Cinema. Our system doesn’t believe in preserving anything. When you research about history of Indian cinema, you would find material about films, directors and actors, but nothing about the technicians. Light and sound aspects are completely forgotten.”

That is partly why he blogs. To maintain a record of his experiences.

*****

Sriram,-CK,-Kareena–Agent-Vinod

He elaborates with an example. “For one of the scenes in Mohenjo Daro, I set the lighting in a particular way, using a lot more lamps than usual. I wanted the audience to feel amazed the way a person from that era might have felt upon walking into that space. Later, when I switched the lights off for another scene in the same set, Ashutosh remarked the scene would have looked prettier with a few more lights. I told him that I didn’t want people to get distracted by the lights. This is the way I approach films. I try to sync my work with the script. I want to sit with the director as much as possible, and want him to tell me what he wants.”

“In Indian films,” he reiterates, “visuals are meant to show the audience the person that is speaking the dialogue. That is why we want Kareena (Kapoor) to look pretty even when she is crying at her mother’s deathbed. I can’t understand such cinema. The two most prominent aspects of cinema – visual and sound are given short shrift in Indian movies. Speak to (sound editor)Rasool (Pookkutty), and he’ll tell you the same thing. In Indian cinema, sound means dialogues and overpowering background music.”

He continues in the same vein. “As a film making community, we haven’t grown much. After 50 years of its release, we are still trying to make a Godfather, while in the West, filmmakers are pushing the envelope further.”

*****

He is even more outspoken about awards in Indian cinema. “I don’t believe in awards. They don’t make me happy or unhappy. Most of the time, the award committees have no idea what they are talking about. They are (made up of) people who are not aware of the actual work (of a technician).”

*****

His favourite cinematographer is Conrad Hall. “American Beauty and Road to Perdition in particular. To think these two entirely different looking films are shot by the same person is amazing. He shot Road to Perdition when he was 75!. I shouldn’t use the word beautiful to describe these films. They are good not because they have pretty actors or beautiful visuals. They are inspirational, and encourage me to do better every time.”

From his own work, he chooses to discuss Rajkumar Hirani’s 3 Idiots. “I get a lot of praise for the climax sequence of 3 Idiots. I did nothing there. It’s just the beauty of the landscape. But there are far more complicated scenes in that film. The delivery sequence, for instance. It was shot in a studio. It was extremely challenging to light up that scene. And Raju’s suicide attempt. Making videos should be made for each movie in Bollywood so that people know what goes into each scene. Hollywood makes them regularly because they respect each other’s work.”

*****

IMG_9884-s

“Maybe that is one reason,” he says before adding with a laugh, “I am a very disillusioned guy. Nowadays I feel that I don’t like cinema as much as I used to. But working with Ashutosh was so refreshing. A great experience. He is an equally passionate guy. He has no pressure on him. He has no fear. If we could not complete a scene today, he would make no fuss about it. “Lets do it tomorrow”, he would say. He made me listen to songs, with the entire unit waiting. And remember, this is an industry where people are terribly scared of songs leaking out before the official release. And this guy would set up huge speakers at the location and make us listen to the scratch version of songs that (AR) Rahman sent. He has that kind of courage. I really enjoyed working in Mohenjo Daro. It was totally a different experience. Usually you are given 15 -30 minutes for lunch on the sets. And here is this man who has no such qualms about time wasted on such things. He would discuss a scene for an hour. He has zero tension about success or failure. At his location, you are not trying to save money. Your only agenda is to make a good film. You are not bogged down by time limits.”

*****

Recommended

That leads him to decry how the cinema industry functions in India. “I am not saying we should be lazy. But isn’t it important to enjoy whatever you are doing? We work like contracted workers trying to finish things by a certain time. Once Moorsel, a Hollywood stunt director who has worked in Matrix, asked me if we had 6 working days a week. ‘If we put up a fight, it’s 6. Otherwise, it’s 7’, I replied. And he said in Hollywood, they don’t work for more than 5 days a week. Here, we think even 6 days a week isn’t enough. We work for 20 hours a day. Not that our movies are so successful and making so much money. May be, after all those years of colonisation, our brains have shrunk. We think life is just to slog, slog and slog.

I try to cut myself off from the camera when I am not at work. I don’t click pictures. I like to laze around when I am not working. I like driving and travelling. I used to read a lot, and now I am trying to get back into it.”

*****

But overall, he says, “I’m more peaceful than ever. I have slowed down a lot. I have decided to live. I don’t stress over silly things any more. Earlier, I used to fight a lot with my colleagues on the sets over creative differences. Now, I don’t do that.”

Another call on his cellphone. We say goodbye.

*****