Filmmaker Tathagata Ghosh is on cloud nine as his short film Doitto‘s streaming rights have just been bagged by OTT giant Disney+ Hotstar. He, however, fears that an independent film may get lost in a crowd of titles on such a big streaming platform.

A “handpicked OTT platform” could be the solution, says Ghosh, in a conversation with Silverscreen India.

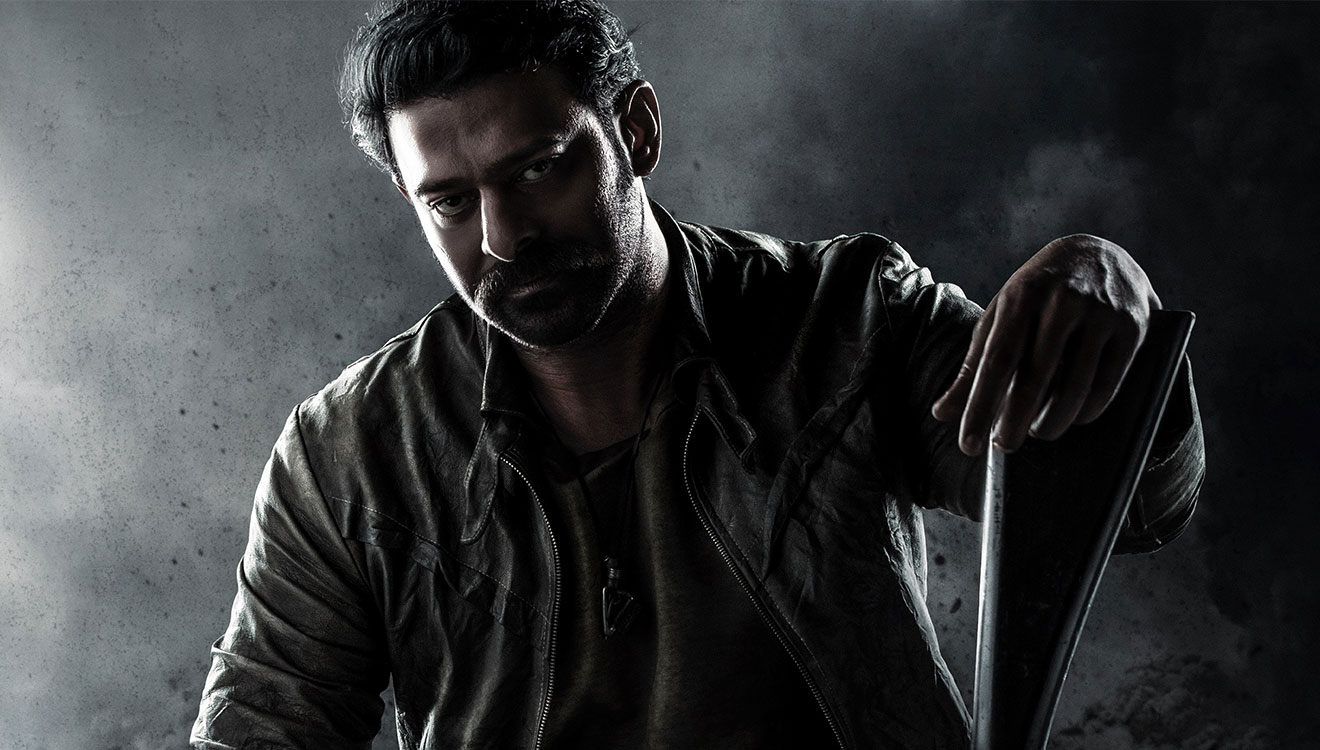

Doitto, meaning demon in Bengali, explores human flaws, the constant struggles of good versus bad and a dark social issue.

“The entire credit for Doitto being picked up by Disney+ Hotstar goes to my distributor Kunal Jhaveri from IndieFilamnt. Going on such a big OTT platform is definitely a plus for an independent film as it helps in increasing viewership,” says Ghosh.

Doitto has received acclaim from film festivals like the 12th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (Panorama), the 24th Kolkata International Film Festival, 19th Independent Days International Film Festival of Germany, eighth Vancouver International South Asian Film Festival, seventh Toulouse Indian Film Festival of France (Special Jury Mention), and more.

1

Talking about the importance of film festivals, Ghosh says: “I think international recognition is very important because it not only helps the film and the makers but also the country where it has been made. Once a film gets that recognition in international film festivals, people come to realise that there are good and talented people outside of Bollywood as well.”

The haunting street art on the walls of Kolkata depicting a small girl, with the word ‘missing’ written next to the drawing, inspired the director to write Doitto.

“It really stuck with me, those paintings, as more and more children went missing every day. Along with that, as I was reading up about serial killers and their psyche, I wanted to do a story regarding that,” he says.

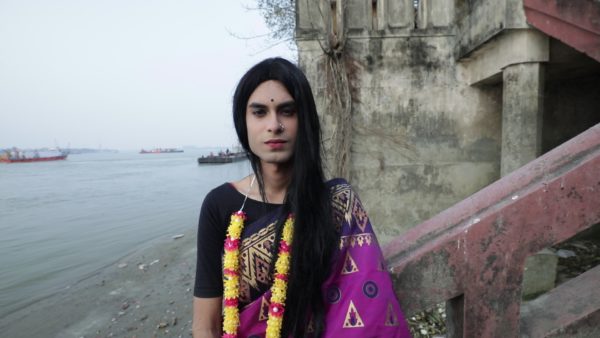

Ghosh recently wrote, directed, and produced Miss Man, which explores the life of a transgender woman, the struggles of a queer individual, and what it’s like to be a queer person in the suburbs of India.

“The film is extremely personal to me,” says Ghosh. “Miss Man came to my mind a few years back when a friend of mine got married. I found out that he came out to his parents only to be forcefully married off after that. This was at a time when Section 377 was still there in our country. I was very disturbed by this event because the marriage broke apart and he went through a lot. A couple of years back I started writing the story, saved money for the shoot, and funded the film myself,” he says.

“There is a great documentary on Netflix called Disclosure which showcases that when a transgender character is played by a cis-male or cis-female, the focus strips from the larger subject to just the actor portraying the character. The struggles of a transgender person get diluted. Sometimes the portrayal also gets very caricaturist. Which is why it is important for transgender people to portray themselves on screen. Many people often tell me does that mean a murderer should play a murderer? I think it is a wrong excuse. Because it is certainly not the same. We have a long way to go when it comes to representation in cinema. It is essential to not only cast people from the community in the story but also behind the camera to have their perspective,” he says.

Elaborating about the representation of the transgender community, he says: “Movies have a long history of being extremely unkind to transgenders. Even a recently released trailer, which has a big star playing a trans character, shows the trans woman as someone who everyone should be afraid of, instead of having a conversation around trans life. Movies have really tarnished the sensitive aspect of understanding a trans person.”

Miss Man has been showcased in several film festivals, including the 34th BFI Flare: London LGBTQ+ Film Festival, the 32nd Vancouver Queer Film Festival, 11th KASHISH: Mumbai International Queer Film Festival, 33rd Out on Film: Atlanta’s LGBTQ Film Festival, 24th LesGaiCineMad (Madrid International LGBTI Film Festival).

Miss Man_still-02

Talking about how OTT platforms have become as a boon, Ghosh says: “OTT is definitely a more democratic platform, though nothing can match the experience of watching a film on a big screen. The thing with streaming platforms is that it gives big as well as small films an equal place, unlike a film theatre where you have to be in the good books of the distributors to get a proper show timing. Another great thing is that OTT doesn’t censor your films, thankfully. In our country censoring means butchering films.”

Even though censoring hasn’t entered the OTT arena yet, Ghosh says he won’t be surprised if it creeps there either.