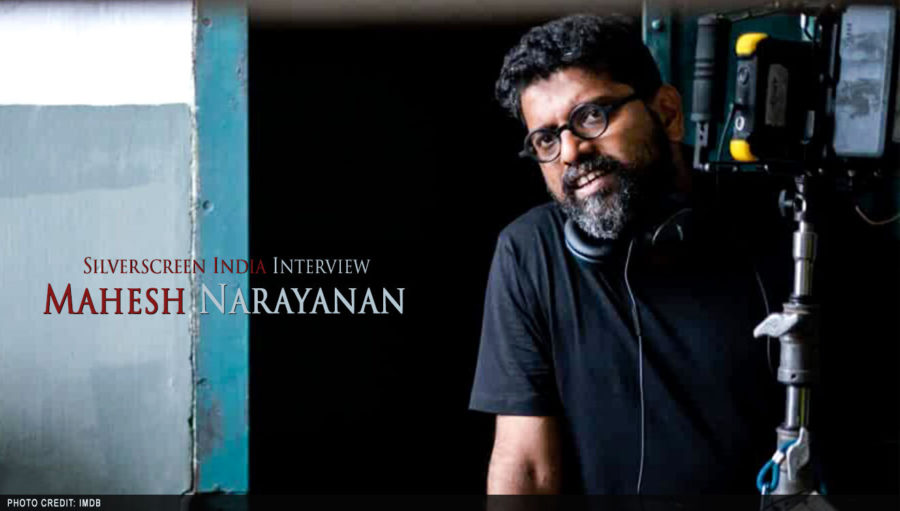

Editor-filmmaker Mahesh Narayanan’s C U Soon, which premiered on Amazon Prime Video on September 1, ends on a wishful note. A promise to re-meet the audience in the cinema halls once the pandemic has disappeared.

C U Soon is one of the first wave of Malayalam films that premiered on digital platforms over the last six months. Shot entirely during the lockdown period, the film is Malayalam’s first screen life movie, a modern format of film making where stories are told from the point-of-view of computer/phone screens.

According to Narayanan, the idea of the film was conceived much earlier, before the pandemic set in and before he and Fahadh Faasil started shooting for their pet-project, Malik, in 2018. When India went into lockdown on March 25, 2020, pushing Malik’s theatrical release to uncertainty, the duo decided to work on a smaller film.

“We wanted to keep things going,” says Mahesh Narayanan. “The OTT release was the need of the hour. Filmmakers cannot work out of a vacuum. We need an avenue to show or sell our films. And there is a workforce dependent on us. Through C U Soon, we could provide jobs for a 50-member crew. It was about survival.”

C U Soon, which has Darshana Rajendran, Fahadh Faasil and Roshan Mathew in the lead roles, is a thriller centred on a victim of human trafficking in Dubai. Mahesh and the team shot the film in 20 days in an apartment complex in Kochi where Fahadh resides and finished the post-production in a little over 60 days.

Mahesh Narayanan began his career as a film editor in 2007 through Lenin Rajendran’s Rathri Mazha. He worked as an editor in close to 40 movies before making Take Off, his debut directorial, in 2017. The film, besides being a commercial success, won several local and international awards, including a special jury mention at International Film Festival Of Kerala in 2017. In an interview to Aswathy Gopalakrishnan, he talks about the circumstance that led to the making of C U Soon, his cinematic influences and his personal connection to Malik.

Like Take Off, C U Soon too is set in a Western Asian city. How did you come across this story?

C U Soon is based on many news reports, many untold real stories. I have friends working in media across the globe who share with me interesting news stories that they come across. Once, a friend sent me a video, which was sent by a young woman in Qatar to her mother. I found it very haunting. At the beginning of the lockdown, when Fahadh and I were brainstorming ideas for a small film, this video came up.

Had it been a different situation where there were no restrictions in place, would you have chosen a conventional cinematic form to narrate this story?

No. I always knew this story needed an unusual technique. I have always been interested in formal experiments like found-footage. I remember watching The Collingswood Story, a found-footage film in 2002 when I was a student. I was so fascinated by the genre. It’s a wonderful way to mix fiction and reality on the same canvas. In Take Off, I have used news clippings and video recordings by people who witnessed the incidents. I had always wanted to make a found-footage/screen-life movie, and the lockdown just became a reason.

When you were writing the film, did you have an exact idea on how to execute it? What were the hardest and perhaps the most unexpected challenges that you faced in the making of the film?

In a screen-life film, the audience has access to the characters’ life only when the latter switch on a digital device. A lot of things happen outside the screen-frame. The script has to fill the gaps. The writing has to be in such a way that the gaps in the plot aren’t felt. For instance, we aren’t privy to the details of how Anu and Jimmy meet for the first time. Did she walk to his car or was he waiting for her in the basement? Were they emotional? I used the digital habits of the characters to etch out their personality. Kevin (Fahadh Faasil), a techie, isn’t worried about his digital privacy. He never keeps his laptop shut down.

Thanks to the unusual format of the film, I couldn’t trust anyone else with it. I was the only person who had an idea what the final out should look like. The entire film is shot in a single lens. There is no mid-shot or cutaway shot. It is on the editing table we do the virtual cinematography that decides how to begin and end a scene, how to move to the next scene, do the breakdown of shots. Being a seasoned editor, I had an impulse on the first couple of days of the post-production about the mistakes we were making. I re-edited it and restructured the narrative an exhausting number of times.

Do you believe cinema has to be watched on the big screen?

Everything is constantly changing and progressing. When cinema moved from celluloid to digital, many people were against it.But now everyone is shooting in digital. I believe streaming will come to be the standard practice in the near future. It will change our perception of how films have to be.

But watching movies in a theatre environment, with a crowd, is something that will never lose its appeal. The audience comes to the theatre, a closed environment, prepared to be entertained and be immersed in the film. They switch off their phones, maintain silence throughout the screening. There is something unique and beautiful about that experience.

You worked as an editor in over 30 films before directing Take Off. Was the transition from editor role to filmmaker smooth?

I don’t see it as a transition. In fact, I worked as an editor in four films after making Take Off. An editor and a filmmaker, essentially, perform the same job. We do story-telling. An editor can have a lot of impact on a film if he/she is given a free hand. I absolutely enjoy being an editor. When you work in the field of cinema for a long time, you learn and evolve to have an understanding of all aspects of filmmaking. Although I don’t have institutional training in cinematography, I learned its nuances from the film institute, and in Take Off, I operated the second camera.

You are known as a filmmaker who uses time efficiently.

I always complete the screenplay to a T before starting the production. Every actor in my film, even the ones who do minor roles, get a copy of the screenplay beforehand. I complete films quickly because I approach filmmaking the classical way. I don’t shoot mindlessly. I shoot only what is needed. If you look at some of the best films in the world, you can see that they were shot this way. Whiplash was shot in 19 days. Clarity of thought is crucial.

From what the news reports suggest, Malik is an ambitious project of epic proportion.

Malik is a project I’d been planning since 2011. It took a long time to come to form. It was an intense exercise for Fahadh who plays the lead role. He is a close friend to whom I bounce all my stories, ideas and screenplays. He never asks if I want him as the lead actor. When I pitched the film to him first, I wasn’t sure if he would agree to play the role.

The film has a 12- minute single-shot sequence in the beginning. But it isn’t an action sequence. I visualise the scenes while writing. I keep edit points in mind. Here, I have used it to establish characters and the space. It tells the audience what the film puts forth. A little while into C U Soon, don’t the audience forget the peculiarity of the form and get engrossed in the story? I believe the content is bigger than the techniques used to narrate it.

When you make films based on real incidents, real people and places, how do you find a balance between entertainment, aesthetics and a responsibility to stay true to the facts?

I look for stories that touch my heart. Malik is important because it’s about a place I am well familiar with. I grew up near Poonthura, a coastal town in South Kerala. I know its geography and its people. The prime subject the film discusses is the politics centred on land. The land is the single biggest factor that shaped this place’s history.

Recommended

At the end of the day, it’s common people who suffer the effects of every political decision, every socio-cultural/geological change. I didn’t look at Take Off as an Iraq-rescue story. For me, it is about Sameera, the unusual decisions she made in life and the circumstances she passed through. Her remarriage, her relationship with her son and her having to hide her pregnancy from him. It is loosely based on the life of a friend, something I witnessed from close quarters. The rest of the things in the film were built later around this character. I keenly follow global geopolitics. I read books, I follow the news. And I had colleagues, ﹣art directors and researchers ﹣and friends in the media and government to help me recreate the space.

There is also the now-popular question on political correctness in films. Take Off was briefly caught in a controversy.

Who has the authority to decide what is politically correct and what isn’t? It is an abstract and relative idea. I believe a filmmaker’s politics will reflect in the films he makes. I don’t regard myself as a person belonging to any religion. In college, I was a member of the Student Federation Of India (SFI), a leftist organisation. For me, Take Off is about Sameera’s rebelliousness. It isn’t Islamophobic. The boy reciting the Quran, a scene some people found a problem with, is based on an incident that happened in Bangladesh. I didn’t create it out of nowhere.