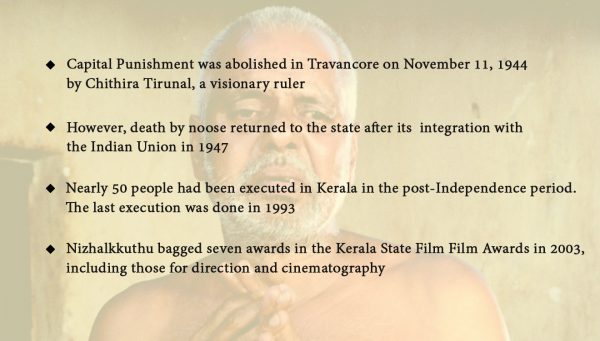

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is one of the pioneers of the ‘New Wave’ in Indian cinema. His first film, Swayamvaram was made in 1972. Since then, in a career spanning over 50 years, he has won the National Film Award 16 times, and the Kerala State Film Award 17 times. His films have been screened at all the major international film festivals. In 2004, he won the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, the highest film award in India. On his birthday today, we revisit his 2002 film Nizhalkkuthu (Shadow Kill).

***

Which executioner is more humane? The one who kills you in a few minutes, or the one who wrests your life from you in the course of many years?

– Anton Chekhov, The Bet.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

In a rare folk version of the Mahabharata from Kerala, is the tale of a tribal black-magician. Duryodhana, the Kaurava prince, entrusts him with a mission to kill the Pandavas through an evil method called ‘shadow piercing’. The black magician, fearing his life, obeys the Kaurava prince and kills the Pandavas by stabbing their shadows. Back home, his wife, a righteous woman, comes to know of this treachery and in turn kills their only child through shadow piercing. For the heinous act that her husband committed, she pushes him into the abyss of guilt and agony.

It is in this tale with many complex layers that master auteur Adoor Gopalakrishnan founded his brilliant 2002 film Nizhalkkuthu (Shadow Kill), an Indo-French co-production.

In the final scene of the film, a young Gandhian nonchalantly steps into a black robe and proceeds to perform his first duty as a state hangman, filling in for his father who collapsed in panic minutes before the execution. The son is a pacifist who has travelled around the state, making speeches against the death penalty. Yet, on this fateful night, he agrees to do the duty without the slightest protest, even though he, like everyone else, knows the boy he is about to hang is innocent.

Why doesn’t the young man try to break free of the traditions that force him to follow the steps of his father? Shadow Kill, in its highly profound way of story-telling, explains why it is impossible to fight violence in a society that believes in a law that calls for an eye for an eye.

*****

While India has produced many films on the theme of capital punishment, rarely has any movie been as subtly eloquent as Shadow Kill. In 2003, it was chosen by Amnesty International as part of its global campaign against the death sentence. It is amazing to see how this film, set in a period before independence, continues to be relevant to this day.

The film is made up of a seemingly uncomplicated exterior – the tale of a hapless state hangman in the erstwhile Travancore empire where the hanging by the neck was a common method of punishment for murderers. But as you delve deep into it, the film gets more difficult to decipher. Adoor himself says that the film will be “better understood when one has seen it, not while seeing it”.

***

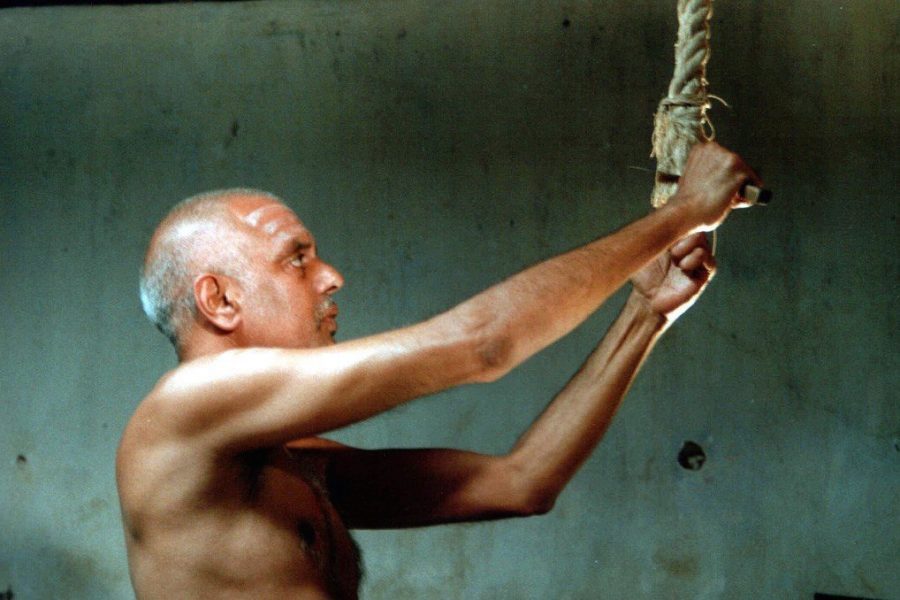

Set in the 1940s, Shadow Kill explores the psychology of violence and retribution through the mental trauma of the last hangman of Travancore, Kaliyappan (Oduvil Unnikrishnan). His is a family profession handed down from one generation to the next. He lives outside the city, in a quiet village, cut off from the centres of crime and activity, on a land donated by the rulers of Travancore. He is also occasionally showered with monetary and other kinds of benefits, for an unspoken service he does for the royal family. He is a ‘sin-bearer’.

Moments before every execution, the ruler revokes the death sentence through an order of pardon. However, it is timed in such a way that the order arrives at the jail minutes after the execution has been carried out. This strange technique, supposedly, absolves the ruler of the sin and makes the hangman the sole bearer of the guilt and sin of executing the man. And how does the poor man deal with it? He believes his job is ordained by goddess Durga.

Ironically, the rope that is used to hang the culprit, later, becomes a divine instrument of life-giving. After the execution, it is preserved in Kaliyappan’s house, in front of an image of goddess Durga. Villagers believe that the ash made by burning the rope can cure ailments.

The images as this, of life and death, recur throughout the film. Kaliyappan’s son, Muthu (Naren, credited as Sunil Kumar), spins strings out of his new spinning mill, a symbol of Gandhism. For him, the spinning mill stands for self-reliance and nationalism. But the strings he makes are later taken to the local prison to make the noose for hanging prisoners. Similarly, an image of menstrual blood trickling down the leg of a girl later acquires a whole different meaning of death and violence.

*****

It is said that Adoor found the seed of the film in a novella written by Vaikom Mohammad Basheer. A line from the book kept him on the hook. It read, ‘I kept watch over death’. The idea grew stronger when he spent some time inside a central jail in Kerala during the filming of Mammootty’s Mathilukal. In an interview to critic Gauthaman Bhaskaran in 2003, the Adoor said that “a hangman’s intense struggle with his conscience” had been bothering him for years. “I grew up listening to stories of ferocious looking executioners with huge moustaches and blood-shot eyes,” Adoor told Bhaskaran. But the question that haunted the director was that could it be easy for a person to fix the noose around the neck of a man he has never seen before.

It is said that Adoor found the seed of the film in a novella written by Vaikom Mohammad Basheer. A line from the book kept him on the hook. It read, ‘I kept watch over death’. The idea grew stronger when he spent some time inside a central jail in Kerala during the filming of Mammootty’s Mathilukal. In an interview to critic Gauthaman Bhaskaran in 2003, the Adoor said that “a hangman’s intense struggle with his conscience” had been bothering him for years. “I grew up listening to stories of ferocious looking executioners with huge moustaches and blood-shot eyes,” Adoor told Bhaskaran. But the question that haunted the director was that could it be easy for a person to fix the noose around the neck of a man he has never seen before.

The film begins with a scene in which Kaliyappan is breaking down in a country bar, trying to drown his grief in alcohol. “He was an innocent young man,” laments Kaliyappan in the memory of the last man he executed, as the bar owner, the only person in the village he opens up to, looks on in sympathy. A day later, a summons arrives from the Prince of Travancore, intimating Kaliyappan of the date of the next execution. The film, from this point, becomes an abstract mixture of reality and fantasy.

The crucial moments of the film happen in its latter half. In a Kurosawa-sque setting inside the jail complex, hours before the execution, Kaliyappan sits drinking with five policemen as Muthu watches from a distance. To keep the hangman awake, a senior warden starts narrating a story. Kaliyappan, grappling with fear and grief, starts hallucinating.

Recommended

This part of the movie has been subject to multiple interpretations. Could this story be Kaliyappan’s recollection of his previous execution? Is the scene inside the jail real or a figment of his imagination? In an interview, Adoor puts forth his version: “In fact, the second part of the film is a nightmare of the Hangman in a state of delirium – about his fear of having to go back to another execution… at one level the film is about experience, memory, and imagination.”

When Kaliyappan passes out, there is a moment of pause. A confusion spreads among the jail wardens whether to go ahead with the execution. But Nizhalkkuthu ends on a sadistic note. Every ray of hope is brutally struck down. The Gandhian proceeds to walk towards the gallows, while the film turns back and looks at the audience, making a compelling plea against the capital punishment.

*****

This piece was originally published on October 11, 2016.