It’s a rare Hollywood film that wears its allegories on its sleeve, but Snowpiercer (2013) did exactly that. Bong Joon-ho’s first-ever Hollywood film, the Chris Evans-starrer was famously sabotaged by its own producer Harvey Weinstein, after the director refused to make the changes he wanted. And while Bong may have paid the price upfront (Snowpierecer barely made a dent at the box office because its promotions were stalled, essentially), his uncompromising vision meant that Snowpiercer was stacked edge-to-edge with genre thrills, painterly visuals and allusive dialogue. One of the most memorable sequences was Minister Mason’s (Tilda Swinton) speech in the first half, pithily summarising the ground realities of the fictional train that gives the film its name: a post-apocalyptic mobile society wherein the haves and the have-nots occupy the front and tail sections of the train, respectively—Curtis (Chris Evans) is the de facto leader of the tail section’s ‘revolution’, advised by old-timer Gilliam (John Hurt).

“Order is the barrier that holds back the flood of death. We must all of us on this train of life remain in our allotted station. We must each of us occupy our preordained particular position. Would you wear a shoe on your head? Of course you wouldn’t wear a shoe on your head. A shoe doesn’t belong on your head. A shoe belongs on your foot. A hat belongs on your head. I am a hat. You are a shoe. I belong on the head. You belong on the foot.”

This speech not only spells out what drives these characters, it also reveals the true scale of Bong’s ambition here—the train, “a closed ecological system” as several characters point out through the course of the film, becomes a microcosm of the way society is organised in most capitalist societies in the world today (including and especially nations that are ‘liberal democracies’, prima facie). The way the story plays out, then, is Bong’s critique of the status quo and though the film is far too smart to offer readymade solutions, the closing moments of the film do offer a symbolic closure of sorts, the beginnings of a roadmap for the days ahead.

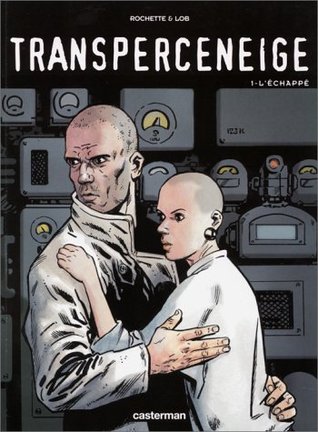

Bong’s film was based on the French graphic novel Le Transperceneige (The Snow-Piercer, 1982) by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette, in many ways a representative European comicbook from the 1980s—stylish, photo-realistic illustrations, favoured mood-setting over dialogue and included generous doses of ‘Camus Lite’ existentialism. Earlier this year, prompted no doubt by Bong’s Oscar and the resurgence of interest in his filmography, Netflix released Snowpiercer the TV series, starring Jennifer Connolly and rapper/actor Daveed Diggs (from the original cast of the hit musical Hamilton), developed by Josh Friedman and Graeme Manson.

2673523

Both the film and the show retain the basic elements of the book’s plot—an unsuccessful attempt to reverse global warming has resulted in Earth freezing over, basically. The remnants of humanity are all packed into the titular Snowpiercer train, built and ruled over by Wilford (Ed Harris in the film, Sean Bean in the series), while the revolution is led by Curtis and Gilliam. The film’s big twist is to reveal that all the while, Gilliam and Wilford had been working together to maintain the unjust status quo, wherein the front section had been hogging most of the train’s resources, leaving the tail section residents with artificial ‘protein blocks’ to eat. Curtis’s ‘revolution’ was just the latest in a series of planned conflicts designed to thin the herd, as it were (“your population will be reduced by exactly 74 per cent”, Curtis is told).

In the show, this idea is introduced in the first couple of episodes itself—we learn that Melanie Cavill (Connolly), the Head of Hospitality on the train, has actually taken Wilford’s place after the latter died years ago. This puts her in a morally ambiguous zone, because Cavill is visibly fascinated by the lives of the tail section residents, and she appears to be sympathetic to their cause. Melanie is therefore representative of the ‘moderate’ elements of autocratic regimes.

The show’s protagonist, Andre Layton (Diggs), is a similarly liminal presence—he is the Curtis-analogue, the rebel organiser who could become the tail section’s champion. But he’s also a Black man who used to be a homicide detective and is therefore recruited by Cavill to solve a series of murders taking place in the train’s front section. The political implications of a Black man becoming the world’s last cop, essentially, isn’t lost on Snowpiercer—at more than a few places, you can see it in the raised-eyebrow reactions of the other characters, when they realise who Layton is.

Cavill and Layton’s shifting loyalties are also indicative of the complex power equations that drive capitalist societies circa 2020. If you work for a powerful enough corporate entity, in practice this can mean State-like powers. The Snowpiercer show’s decision to ‘upgrade’ the moral ambiguity in these characters is, therefore, entirely on point.

In 2018, the journal New Political Science published a paper by Fred Lee & Steven Manicastri, called “Not All Are Aboard: Decolonizing Exodus in Joon-ho Bong’s Snowpiercer”. The paper gives us some fascinating insights into the allegorical narratives of Snowpiercer, and the real-world political structures the film critiques. According to Lee and Manicastri, the tail section of the film represents Third World Nations while the front section is a stand-in for the developed, mostly white West—notional liberal democracies that function more like corporate oligarchies. Crucially, the encounter between Curtis and Nam (Song Kang-ho), the designer of the train’s security features is framed in a very interesting way. Curtis, of course, is looking for Nam because the latter holds the key (literally) to the revolution’s chances of reaching the front section.

MV5BNDk1MDY2NTI3M15BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMDU1NDQ3MTE@._V1_

As critics other than Lee and Manicastri have noted as well, ‘Nam’ is a stand-in for ‘Vietnam’, while Curtis is an inter-textual analogue for America, because of Chris Evans’ worldwide fame as Captain America in the Marvel film franchise of the same name. According to the authors, the alliance between Nam and Curtis represents a way forward for a world ravaged by the excesses of capitalism —America and the rapidly-industrialised ‘global South’ working together for a better tomorrow. The working-class (and tech-savvy) American and the Asian industrial worker—you’d be hard-pressed to find two demographics more thoroughly disillusioned with 21st century capitalism.

In that vein, the relatively minor character Paul (Paul Lazar) is analysed through the authors’ ‘decolonising’ lens. Paul is the one who makes the protein blocks for the tail section residents—he is ambiguous about Curtis’s revolution and is content to keep on doing what he has been doing for years (ie making artificial food from insects). “Paul would be considered a white American male in the pre-apocalyptic world, but unlike many white American males today, Paul is content with his work and his life. Inhabiting an isolated car, he produces the tail section’s food, “protein blocks” made from insects, to the beat of nostalgic rock music. Paul represents the “sleeping beauty” of the metropolitan proletariat, who side with their nation’s bourgeoisie on questions of empire. This alliance is signaled by the fact that Paul hides Wilford’s messages in the protein blocks, messages which Curtis wrongly assumes come from a head section ally.”

After this betrayal, Paul also becomes the ideal stand-in for working-class Americans today, most of whom voted for the autocratic Donald Trump in 2016, a full three years after the film released. So the question then becomes, can technology (ie the high-tech engine that Wilford built) help us bring diverse demographic groups together, or does it only serve to deepen existing divides?

Screening-Bong-Joon-Hos-SNOWPIERCER-Curtis-and-Wilford-3

Lee and Manicastri write: “As the inventor of the train, Wilford once harbored the utopian hope that ‘technico-scientific intelligence’ would present unforeseen possibilities for humanity. As a ruler aboard the train, Wilford adopts the more ‘realistic’ hope—akin to Nolan’s in Interstellar and Boyle’s in Sunshine—that scientific technologies will secure human survival. Putting more stock in the political meaning of revolution, Bong questions what role high technology can play in saving our species.”

Snowpiercer’s last half-hour reveals where Bong stands on this—we learn that the technology of the engine isn’t nearly as smooth or as automated as Wilford claims it is, initially. The train uses human children to replace some of its moving parts; a perpetual supply of tail section children therefore serves as the cruelest fuel in the world.

Recommended

After an explosion-triggered avalanche derails Snowpiercer in the film’s climax, all but two passengers are killed off. The survivors are Nam’s 17-year-old Yon (Go Ah-sung) and little Timmy, the 7-8-year-old son of Tanya, one of Curtis’s rebel soldiers. As they step out of the train, they see a polar bear in the distance—while this signals future threats for the last two human beings on the planet, it is also a sign of hope. Hope because for the first time since Adam and Eve, humans and animals are on an even keel; humans have nothing by way of technology or weaponry that gives them an unfair advantage. The sight of the polar bear is an indication that Yon and Timmy might start a new kind of civilisation, hopefully a much saner one this time around.

Also read, What To Stream: Bong Joon-ho’s ‘Parasite’ Gets Floods And Disparity Right