Blaming reviews for poor box-office performance is bad, but there’s something worse that nobody wants to address: the rise of the ‘journalist-promoter’

On Sunday afternoon, several movie stars spoke at an event in Chennai to release the audio of Neruppu Da, the first movie from actor Vikram Prabhu’s new production house. Among the speakers were Rajinikanth and the newly elected president of the Tamil Nadu Film Producers Council, actor Vishal. As is typical at events of this nature, the attendees only briefly spoke about the audio of the movie before moving on to other things.

Vishal, who now holds office in both the South Indian Film Actors Association and Producers Council, started with praise for Vikram Prabhu (The swagger in the title, Neruppu Da, caught his eye), Vikram’s parents ( “They are the most hospitable couple”) and their cooking (the biriyani was singled out for special praise). And then, he changed tack.

“The media,” he said, “you are part of the family. You are part of the film fraternity. And I would like to request you to not review movies on the day of release. I understand journalism requires freedom of expression. That is why I am requesting you, as a fellow human being, to refrain from reviewing movies for at least three days. ” And in case it was not obvious, Vishal immediately made it clear that his request was aimed at reviewers on social media, “those who trash a movie on the first day and then claim that their reviews are the opinion of people.”

Speaking after Vishal, Rajinikanth echoed the concerns, asking the media to review movies without “hurting the filmmakers. How you communicate a message, the words you select, that matters,” he said.

*****

The reactions to the request were swift and brutal, with one writer calling the film fraternity a “big crybaby” for blaming reviews for poor box office performance, and journalists on social media claiming that there were no objections when their reviews were positive. Last year, during the release of director Mani Ratnam’s OK Kanmani, Suhasini Maniratnam faced similar criticism for proposing that only “qualified” reviewers be allowed to review movies.

The reactions in both of these cases miss an important point. The issue is not that the reviews are published too soon, it is that Kollywood believes they are unfair and biased. And they have good reason to believe that, because cinema journalism in Tamil is shamefully corrupt.

Several cinema journalists in Tamil are also movie promoters who are paid by movie units. And many of them are also gainfully employed by respected media outlets. This does not seem to faze the outlets.

*****

Embargoes on movie reviews are not uncommon, but those are usually requests by producers to not publish reviews until a movie is open to the general public. Many Hollywood-based production houses are known to delay or cancel press screenings if they think the reviews will be negative. In this case however, the request was to delay reviews until the first weekend after release.

Most Tamil movies made in the last few years do not return enough money to cover production expenses. The film industry has been confronted by several crippling problems of late, chief among them the availability of readily available, inexpensive entertainment options. The advent of “mega serials” on television has robbed movies of female moviegoers and piracy is rampant. Ticket prices are high, and there are non-Tamil options in multiplexes that compete with Tamil films. Tamil film production and financing are still done the traditional way by independent producers who sometimes stand to lose their life-savings when a movie does not do as well as expected.

Until not too long ago, Tamil movie reviews were the domain of weekly magazines like Anandha Vikatan, and moviegoers had to wait several days to get a movie review. Now, reviews are out in hours on social media. Several channels on Youtube dedicated to reviewing Tamil movies have steadily increased in popularity, luring viewers in with chatty, no-holds-barred reviews.

On one of the more popular channels, TamilTalkies, a reviewer, dressed in trademark blue slacks, deadpans bitingly funny criticism about films. Reviews from channels like these are what draw the ire of producers, but TamilTalkies is popular for good reason: Their reviews are funny, insightful, and entertaining.

The producers are worried and desperate, and believe it is such reviews that harm their movies at the box office. But what hurts is not a harsh review from channels that are entertaining, it is that even a genuinely positive review is looked at with suspicion by readers: “Did the producer buy you off?,” is a question often asked.

*****

On Christmas day last year, an interview of the Tamil film director Suraj (to the YouTube channel Cinema Pesalam) in which he speaks with remarkable candor about how he expects his female leads to dress on screen, was the subject of heated criticism on Twitter.

Responding to a comment from one of the interviewers about how Tamannah Bhatia, the female lead in Suraj’s latest release Kathi Sandai, looked prettier than usual, Suraj speaks openly about what he thinks his audience wants.

“My audience pay money to watch a movie so they can see women in skimpy costumes. I pay my heroines good money and insist that they wear outfits that are glamorous. If the costume designer comes to me with an outfit that is too long, I order them to shorten the hem. It doesn’t matter to me if the heroine is uncomfortable with the outfit.”

The interviewers – both male – are seen laughing throughout the minute long answer, and assure Suraj in a follow-up question that none of the costumes made the actor ‘look vulgar’.

If the comments were shocking for their casual sexism, they also affirmed the worst suspicions about the role of heroines in mainstream Indian films. “(Mainstream) heroines are sought-after only for their sex-appeal,” Suraj says, “not for their acting prowess. Maybe if they act well, they can get cast as leads in a TV series or two.”

The first reactions on Twitter were from fans of the actor, who called out the director for his comments demeaning their idol, but neither the director nor the interviewers chose to react. In a comment to Silverscreen, Suraj revealed that he was uncomfortable with his comments as soon as the interview went online, but chose not to react publicly.

The next day, Nayantara – as big a female star as there is in Tamil now – in an interview to the online magazine Sify commented on the controversy. She recognised that the problem with Suraj’s comments was not the length of his costumes, but his insistence that his heroines had no choice but to comply because he had paid them a salary.

“And by making such comments that heroines take money to shed clothes, he is misleading the youngsters who will think this is what happens in cinema. I too have done my share of glamour in commercial films not because my director wanted to please that particular ‘low class’ of audience, but because it was my CHOICE. No one has the right to think that heroines can be taken for granted,” she said.

The controversy gained steam after this, and several journalists and actors – including Tamannah Bhatia – joined Nayanthara in condemning Suraj. The director soon issued an apology and promised to respect his heroines more. Criticism was also directed at the interviewers for their seeming approval of the comments and the lack of push-back about the blatant sexism in the answer.

Actors, including Karthik Kumar, Sripriya and Radhika Sarathkumar were vocal in their criticism of the interviewers, Ramesh Bala and LM Kaushik. In response to the criticism, the interviewers removed the interview and put up an apology online where they said the laughter was in response to “inadvertent candidness” and not a sign that they approved of his comments.

The general refrain of the comments was that the interview was bad journalism, and that the interviewers had failed to show journalistic diligence by not questioning the comments made by the director. Kaushik, responding to criticism from a journalist named Rinku Gupta, framed the mishap on journalistic inexperience. “Not an Arnab or Pandey to take him on. Still a beginner in videos,” he tweeted.

But here is the problem with this framing: The interviewers are not journalists. They are movie promoters who are paid by movie units to promote their films on social media.

This interview and the reactions to it expose a much more deep-seated problem with movie coverage in Tamil.

Large sections of media rely on money from the movie industry to sustain themselves financially; and it would be silly to expect them to be fair or balanced when covering their paymasters.

*****

In September 2014, the Tamil Nadu Film Producer’s Council and FEFSI announced their intent to limit the number of outlets invited to cover movie related events to under 40. In response, the Tamil Film Media Federation, a group representing several Tamil journalists that cover films and film related events, released a strongly worded and sometimes colorful statement condemning the decision. (“Without media, movies will turn into“Iruttu sandhil virkappadum karuppu mai”). The statement accused the Producer’s Council of unfairly targeting Internet-only media organisations, and called for a boycott of all film-related functions and events for a month.

The limitation has been loosely enforced, and although Silverscreen is allowed to cover events, we’ve repeatedly argued that it sets a dangerous precedent for any entity to selectively deny permission to some media outlets to cover events.

But the problem is not as simple as that.

It is widely known that most Tamil movie producers traditionally pay media organisations that cover their event. It is easy to condemn this as bad practice (it is), but it is not the main source of the problem. Most reporters and photographers are poorly paid, and these payments are an important part of their income.

It is widely known that most Tamil movie producers traditionally pay media organisations that cover their event. It is easy to condemn this as bad practice (it is), but it is not the main source of the problem. Most reporters and photographers are poorly paid, and these payments are an important part of their income.

There are hundreds of web portals that cover Tamil films, and most of them rely on movies to provide content, and movie-makers to provide revenue.

This is an artificially sustained eco-system that cannot last.

This is also why producers want to limit the number of outlets that cover their events. It costs them money.

*****

Recommended

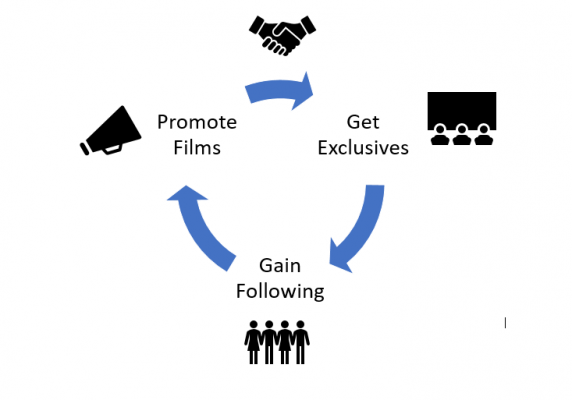

As Internet penetration has grown in India, social media has become an important promotional tool for movies. This has led to the rise of several social media ‘influencers’ – enterprising people that own accounts with a lot of following – who help promote movies. Sadly for journalism, journalists have been at the forefront of this trend of using social media following for “influencing.” Several freelance Tamil journalists have accounts on Twitter with significant following, and many of them promote films. They get paid either in cash or in kind – access to breaking news from their favourite producer, exclusive interviews with a star. Worried producers have started believing that social media visibility is a sign of success and this has led to the rise of the journalist-promoter; someone who promotes movies while also being a journalist.

They use the tools of journalism (breaking news online and doing interviews and box office summaries) to gain following; and use the following to promote movies and gain access to more news (the cast of the next film, an exclusive interview!). In the short-term it is a brilliantly effective tactic for everyone except the paying public.

But long-term, the journalists have more to lose. The public will wisen up to glowing reviews and Tweets about bad movies and start getting their news elsewhere.

Producers will move on to more effective marketing techniques.

And the journalists will be left with followers on Twitter.

*****