Director: Achal Mishra

‘You want to know if there is anything good that can be said about Bihar?’ In Patna, an editor had asked Shiva Naipaul that question, and he answered, ‘The truthful reply is no. I cannot think of a single good thing to say.’

– A Matter of Rats: A Short Biography of Patna, Amitava Kumar

While Naipaul’s derision might be at the dire end of the spectrum, critiques of Bihar abound—some deserved, some unfairly reductive. In Bollywood cinema, it is largely depicted as a land of violence, crime and anarchy (Shool, Gangaajal and Apaharan for example). More recently, it was a setting for Half Girlfriend’s rags-to-riches protagonist to indulge his philanthropic urges. Most Bhojpuri films feed into stereotypes and perpetuate others with their sexist tropes.

In this milieu, Achal Mishra’s debut fiction feature Gamak Ghar wrests the narrative to touch upon another aspect of Bihar—emigration. Decades of economic stagnation and social unrest have led to people across classes and castes leaving the state for a better life. According to the 2011 census, 7.5 million people migrated from Bihar to other parts of India, second only to Uttar Pradesh. About half the households in Bihar have at least one migrant. From January-June 2017, Bihar sent more workers to the Gulf than any other Indian state.

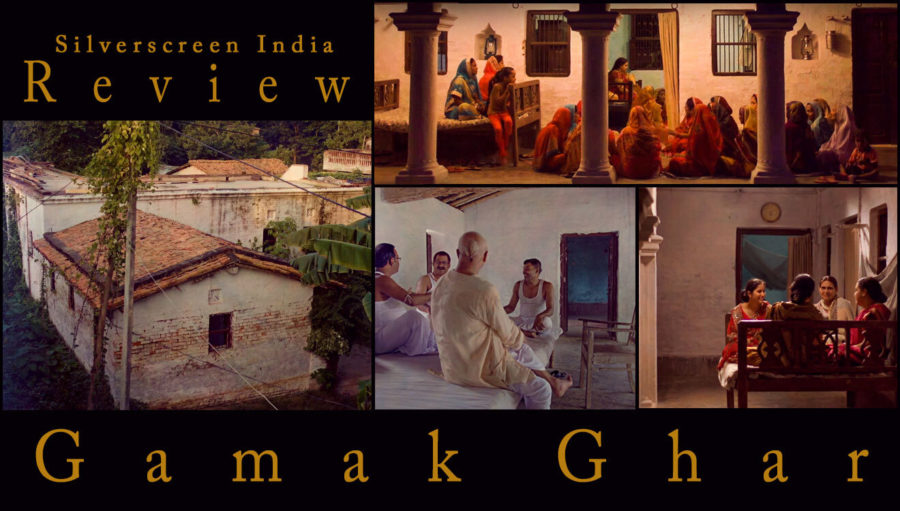

Gamak Ghar, though, isn’t about migration, even though it is the pivot on which the film unfolds. The movie chronicles a Maithil Brahmin family’s ancestral house and the changes it undergoes over two decades. In 1998, the family comes together during the summer to celebrate the birth of a child and host a feast. They play cards, run errands, banter and watch movies on the VCR.

In 2010, we see them congregating during the Chhath festival. Times have changed though—the film camera has given way to the DSLR and fritters to Maggi. The house bears signs of disrepair and tensions between family members come to the fore. Conversations seem stilted. Even the jokes are turning sour. Those who have made a life for themselves in Delhi and Darbhanga are prospering, while those in the village are struggling.

By 2018, just the empty shell of the bungalow’s thriving past remains. With most of the people who made the house a home gone, the inevitable dawns—the old must give way to the new.

The languor of vacations in the village suffuses the first two parts—hide and seek, plucking mangoes, photography, skimming through memorabilia. The static long shots, often with little action in the frame, echo this torpor. With each passing decade, the aspect ratio widens and the warm tones and fuzzy visuals become colder and starker. The comfort and intimacy of the 4:3 aspect ratio of 1998 is a world apart from the widescreen frame of 2018, whose empty, alienating feel intensifies with the fog shrouding the village. Each part is shot in a different season—summer, autumn and winter. These distinct visual palettes reinforce the transformation the house undergoes.

The dialogues, in Maithili, seem unscripted—as if we were overhearing a family’s quotidian conversations. Gamak Ghar is one of the handful of films in the language.

The dialogues, however, are sparse and there isn’t much of a plot. In a sense, the home is the plot and the protagonist of the film. Even the cinematography emphasises the home rather than the characters. The camera frequently dwells on the geography of the house—the brick walls, pillars on the porch, window grills and the tulsi plant in the courtyard. Long and mid shots predominate, with the physical features of the house in the foreground or looming large in the background. There are hardly any close-ups, so we always see the characters embedded in their surroundings.

Gamak Ghar enchants with its overarching attention to details. From the gleaming white walls of 1998 to the damp and blotches pockmarking it a decade later to the utter dilapidation in 2018, the excellent production design and cinematography make it seem as if the film were actually shot over two decades.

As someone from Bihar, there was plenty that resonated even though I grew up in a different milieu—a Muslim family in Patna, far from the Mithila village of the film. The sloping roofs with clay tiles on serrated asbestos sheets; the Z-shaped projections on windows; the relatives asking, “Do you recognise me?”; the discovery of my forebears’ hand-written ledger books; and the distant thrum of folk music during Chhath were also part of my childhood. Watching Gamak Ghar was a delicious exercise in nostalgia.

This nostalgia of the emigrant has lately permeated many works on Bihar. Amitava Kumar talks extensively about his reckoning with the state in Bombay-London-New York, his biography of Patna and several articles. The film Mithila Makhaan features a professional in Toronto who returns to his village in Bihar, only to find it irrevocably changed. A 2014 Bihar Tourism ad and Nitin Chandra’s Chhath music videos harp on traditions. These depict and are aimed at emigrants. There is even a Hindi novel, aptly titled Non-Resident Bihari, about the experiences of Biharis preparing for the civil services in Delhi.

Recommended

Delhi-based journalist Chinki Sinha describes this departure and reckoning with the past in an essay in the DailyO: “I left because that was the only thing to do. Everyone left. Growing up we wanted to leave Patna and its limited life, and so we lived in the future for the most part. Patna changed over the last 15 years that I have been away. There are malls and coffee shops, and even a discotheque now. But there’s a city that belongs only to you, and there’s a notebook with memories of those that are no more.”

Gamak Ghar revels in memories of a home that nurtured generations—until they stopped nurturing it. Its nostalgia, however, is a narrow gaze tinted by the lens of idyllic vacations. Bihar’s feudal society, caste oppression and crumbling infrastructure are beyond its field of view. But these are stories for another film. Hopefully, Gamak Ghar will release the shutter to more movies that present the manifold realities of Bihar.

The Gamak Ghar review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreenindia.com and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.