How does one view Seththumaan? As a simple tale of a grandfather and orphaned grandson living life or as a nuanced take on caste and class differences, and the disdain for food choices and the resultant shaming? Actually, both. That is what makes director Tamizh’s debut film, produced by Pa Ranjith, which has done the festival circuit before being streamed on SonyLIV, very special.

There’s a lovely kernel of a story that can be enough to charm the casual viewer, but for the more involved one, Tamizh populates his film with enough to deserve a re-watch and then some more. There are so many people to focus on — the grandchild, the landlord, his wife, the grandfather, Ranga, the angry rearer of pigs — and each of them gets an arc.

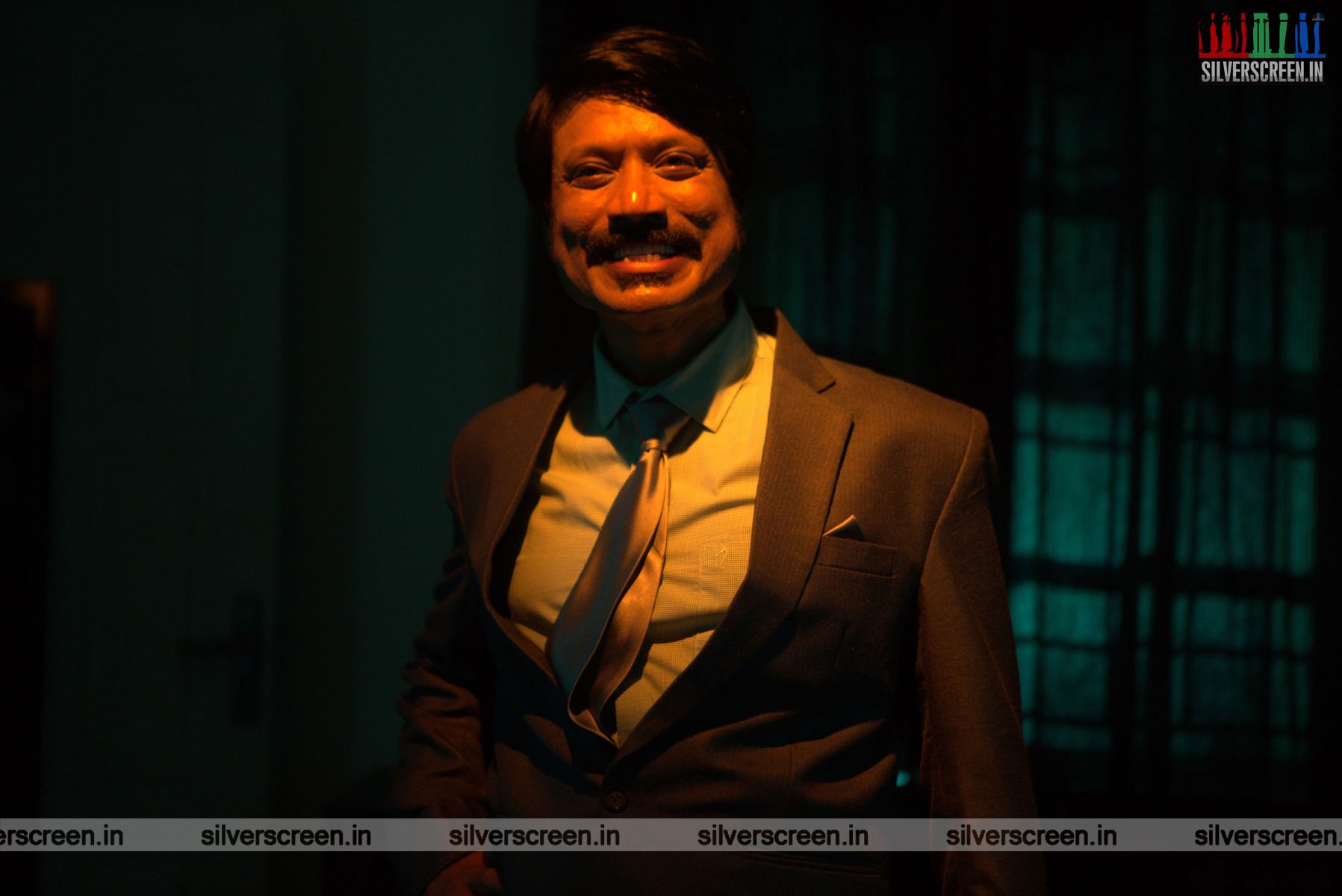

Tamizh’s writing comes from a place of deep understanding of prevailing caste and class hierarchies. And so, while outwardly, Vellaiyan (Prasanna) seems to be a man with heart and one who cares for Poochiappa, also known as Poochi (Manickam), ensuring he gets the first portion of the meat and telling him he will employ him in a possible new land he’s slated to buy, so that his grandchild can be educated, you know that this is more a relationship of an occasionally magnanimous owner and subservient slave than equals.

Poochi is beholden to Vellaiyan and so, even though he likes to stay away from violence, having seen firsthand his outspoken son get killed and pregnant daughter-in-law get fatally attacked fatally, he gets drawn into Vellaiyan’s fights with his relatives.

The film, adapted from writer Perumal Murugan’s Varugari, is set in Western Tamil Nadu or the Kongu region, and the Tamil in the film is rich in the dialect. The dialogues feature wordplay typical to the region, the sing-song delivery and the nakkal (sarcasm) it is known for. Little wonder, the dialogue writer is also Perumal Murugan.

Seththumaan is just short of the two-hour mark and it is to director Tamizh and editor CS Prem Kumar’s credit that you don’t really focus on anything other than what’s on screen. While he cuts to show us the big picture, the camera (Pradeep Kaliraja) also focusses on the little things that make life liveable. Look out for the scene where a relative offers to raise Kumaresan, closer to a better school. The grandson, played by Master Ashwin, who is so full of life and very content being by himself, hugs his grandfather tight without a word. At night, he holds his grandfather like he’s all he’s got. Suddenly, a ball of sadness shoots up your throat and chokes you. What will become of this child, who is the class topper and for whom his grandfather has such high hopes?

Poochi’s grandson, whom he affectionately calls Ponnukutty (little gold), is very fond of studying; you can see him reading under the streetlamp. He has also adopted new-age ways, when he casual says ‘bye’ to his akka but he’s also charmed by what his grandfather does. He sits on his haunches and watches with curiosity as a pig takes its last few breaths, wants to chip in when Ranga and Poochi scald its hide and deskin it. This is something Poochi tries hard to keep him away from — he wants him to become a big officer and move away from the life they currently lead. This is one thing that keeps plaguing you, long after the end credits. Will the child overcome his circumstances or will he succumb to them? Especially because his school in the village is to shut down as the numbers in students are dwindling. Will Kumaresan be able to pursue his studies? All this plays out, even as news of Ramnath Kovind being elected President comes in, and continues until he takes the oath of office. Some people might be able to overcome their lot, but can all?

A film like Seththumaan is important because it nudges you to think of everyday inequities and the skewed power of balance in society. This, it does by hand-holding you through life in a village — most importantly, the gaze is not that of an outsider. Yes, there are lovely shots of Western Tamil Nadu’s lovely hill ranges and mountains and the pretty white clouds and patches of greenery, but the focus is on life and people — the tea shop owner pulling out paper cups for Ranga and Poochi and giving them glass tumblers only after Ranga raises his voice. Vellaiyan’s cantankerous wife, who has a problem with everything including her husband eating the meat of an animal that “eats human faeces”, always shortchanges Poochi for his artfully-woven, sturdy bamboo baskets — only occasionally does Poochi raise his voice, even this he does by telling her she can have it for free.

Your heart breaks for Poochi, who always tries to rise above his circumstances and be the better person. He’s always calming people down, making his Ponnukutty smile, by performing folk art for him, he’s the gentle soul, whom everyone loves and wants to help out.

Ranga, who is always angry as he is aware, and despite his necessity to maintain a monetary relationship with Vellaiyan, is able to tick him off, when he asks if his pigs are clean. Ranga is what Kumaresan’s father might have been, had his life not been cut short — in a scuffle over some cattle dying in a week. One of the reasons why Vellaiyan has an issue with Ranga is possibly because he’s independent and free-spirited, unlike Poochi. With Poochi, he is able to feel magnanimous. Ranga, on the other hand, teaches him that treating someone as an equal is not a choice.

It’s interesting that the food politics in the film originates in Vellaiyan’s family. All the upper caste men who crave the meat of the pig fear ridicule, and face it too.

You see many Poochis in life, you might even see the odd Ranga and react the way Vellaiyan does — “these people have begun to speak a lot” — but what Seththumaan does is show you their lives, up-close and personal. A thatched home in the midst of a farm, with a line full of clothes, a hungry goat that chomps away at hay the entire night, a grandson and the only person who is his.

Seththumaan also shows how in the skirmishes of the rich, even if it is over a few pieces of fried pork, ultimately, the poor are left to grieve alone.

Tamizh has an assured voice that shines through in every frame and in what he’s got his technical team to come up with. Sound designer Antony BJ Ruben literally transports you to the villages of western Tamil Nadu, with the unique sarasarappu (rustle) of leaves in the breeze and the sound of the weaving loom, the traditional occupation in the area. Music composer Bindumalini is such a treasure and it is a pity that many more have not tapped her ability to become one with a movie’s landscape.

Recommended

Seththumaan is also one of those rare films to talk about the way it ought to be spoken about — bloody stools and piles, and what the heat does to people is casual everyday conversation. What about the humble pig or the seththumaan (the deer of the slush)? While Ranga might be dealing in pigs, he calls the one he chooses for Vellaiyan, his rasa (king), and wants him to die a painless death, during the slaughter. Even in death, the pig provides for quite liberally; 10 portions of meat, some varugari and a pocketful of cash for Ranga. It also snatches away, as liberally. Little Kumaresan would know.

*****

This Seththumaan review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the movie. Silverscreen.in and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.