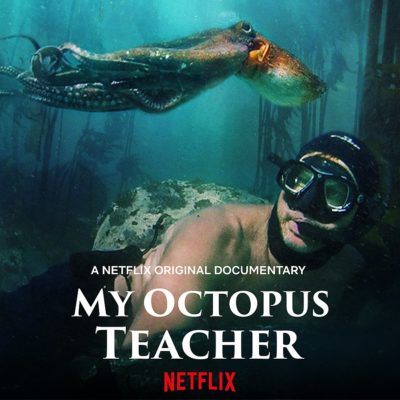

Three weeks ago, the team behind the documentary film My Octopus Teacher was flooded with several hundred congratulatory messages on social media for winning the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature at the 93rd Academy Awards held in April 2021.

Famous personalities like the President of the Republic of South Africa and the African National Congress, Cyril Ramaphosa congratulated the team on Twitter. He said that the film had opened a window into the natural beauty and biodiversity of South Africa’s oceans and marine ecosystems.

I saw its real impact though, when my 86-year-old grandmother from Chennai, reeling from the loss of a loved one due to COVID-19, watched the movie with rapt attention and awe. “There is so much about life that I do not know about,” she said.

The film which showed documentary film-maker Craig Foster’s friendship with a common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) in the southern shores of the Cape Peninsula, ended up being an escape for those looking to flee the horrors of the global pandemic.

For about one year, Foster dived into the cold Altantic Ocean to observe the life of this octopus he had befriended. He did all this without a wetsuit. Although it began as a journey to intimately know his habitat and escape burnout due to pressures of work, the octopus’ life quickly became a daily project.

Foster would wade through the thickets of the Great African Seaforest populated by kelp to observe and understand the movement of this octopus and watch her shapeshift, change colour and even walk like algae.

He showed the audience that she was a curious mollusk, a playmate, a hunter and a highly deceptive prey. Through the journey, viewers like my grandmother attached emotions to her. When she played, they celebrated her. When she escaped the deadly pyjama shark, they cheered her on. In the end, they let her go gently and gracefully.

The documentary took audiences through a range of emotions and became a favourite during award season.

The film, directed by Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed, won both the Oscars and BAFTAs.

Associate Producer and Production Manager of the project, Swati Thiyagarajan said that since the release of the film, the team has received deeply personal messages, including long ones from children, about its impact.

Thiyagarajan, who is Craig Foster’s wife and a filmmaker herself, added that the film gained traction purely through kind words by those who watched the documentary. The conservationist, originally from Chennai, has worked for years in the field of environmental journalism.

She speaks to Silverscreen India about what it was like to see and hear about the incredible octopus, her role in the creative process and the efforts taken to track animals under sea. She also talks about being a core member of the Sea Change Project co-founded by Foster, which looks to actively protect the Great African Seaforest.

What’s life like after the Oscars, BAFTA? Has there been a lot more interest about the relatively unknown kelp forests? Are more people coming forward to monetarily support the Sea Change Project?

There has been as expected a lot of media interest. The interest in the movie has been growing since its release on Netflix and we have had a massive growth in the number of visitors to our sea change project website. We have had people subscribe to our newsletters and our social media presence has grown.

Craig mentions that he was burnt out at work and that diving in the cold sea helped in stimulating him. Did the dives initially begin as an escape? Was his interest in the kelp forest generated only after several months of swimming in the sea?

He had been diving in the kelp forest from when he was a child and had always loved the ecosystem. It was why when he felt the burn out, he chose to start diving in that ecosystem every day. However, all of his diving up until then was just about being in the ecosystem, but when he started to dive every day and adjust to the cold water, he went in with the intention of also learning the ecosystem.

He wanted to immerse himself fully into that environment like he had observed the San people in the Kalahari do, so while he always loved the kelp ecosystem, it was now that he was focused on really studying and exploring it. He co-founded the Sea Change Project, a not-for-profit conservation action organisation for this purpose.

Credit: Sea Change Project.

How did diving without the wet suit help? How long can Craig stay under water without coming up to breathe? How long can you hold your breath?

Being without a wet suit enabled him to feel like he was part of the environment. It enables him to move and swim and be in that environment in a more organic way. He can hold his breath for as long as he needs to get a shot …we don’t really time it. On average about 2-3 minutes and it can go longer if needed. I can hold my breath for about 2 minutes …again I don’t time myself.

Since the octopus was tracked every single day, what were the challenges while shooting on days when the weather was bad?

You can’t really get too many shots when the weather is bad unless you are especially shooting to show how bad the weather is and how big the ocean can get. She was tracked a lot but often it was more a quick check in, because sometimes she would just be inside the den or sleeping or something. Of course, it was easier to shoot when she was out and there was good visibility in the water. Placing the camera on the sea bed or different cameras in different spots to get shots requires for the ocean to be a bit calm.

What did Craig say to you when he first met The Octopus Teacher? In your articles, you mention that you took a while to begin swimming in the sea due to a near-drowning incident. What was your first interaction with The Octopus Teacher like?

A few days into meeting the octopus for, the first time is when Craig said he felt like she was an unusual animal as she seemed curious and willing to interact and that she was always there when he dived, so he was intrigued by that. I had a near drowning incident as a child and I was terrified of water for a very long time, and I would only go in very rarely. I would wear a wetsuit, a life jacket and literally just float on the surface, so I saw her a few times from that vantage point from up in the water looking down so I never interacted with her, but I got a good idea of the area she was in.

In the documentary film The Great Dance directed by Foster, the San people often speak about becoming the animal and thinking like the animal while tracking it. What was the atmosphere like when the octopus was briefly out of radar for a couple of days? Did other people from the Sea Change Project come together to help track her?

No, all of the tracking is something Craig developed underwater on his own. And at the time he was with the Octopus it was really only him. Sometimes Roger Horrocks, his great friend and also amazing underwater camera person, would dive with Craig to get shots. Over time Craig understood her behaviour well enough to predict where she might be and what she might be doing. So that made it less stressful.

It’s only in the last few years that all of us from the Sea Change Project have been swimming and diving as well and learning to track from Craig. Learning to become like that animal happens when you study that animal so deeply that you observe so much and deeply understand the behaviour. Some of it is intuitive, like we get attuned to people or animals we spend a lot of time with, but much of it is in the practice of daily detailed observations where then you understand the behaviour very well and can then predict that particular animal’s actions.

Craig Foster often speaks about having wanted to protect the octopus from predators. What was it like to see predators chasing the octopus? How does one navigate the thin line between interference and non-interference in such an ecosystem?

Non–interference in natural processes is important. If an animal you are observing has a fishing line or hook stuck to it for example, you can try to help remove that. If it’s a predator–prey moment you cannot interfere. Craig by the sheer volume of time spent in the water was also equally familiar with the other animals in the water. Pajama sharks are exquisite animals and they live almost 20 times longer than the octopus and they have challenging lives and when you see those lives and you see what it takes for that shark to hatch from an egg to grow to adulthood with immense challenges, you love and respect that shark too. So, no interfering in the natural processes.

Wildlife filmmaking as a whole happens when people dedicate time effort and energy into following or studying an individual animal or group of animals, none of the filmmakers will interfere with the natural process. Let’s say someone is making films on zebras and has followed a baby zebra till it’s grown to adulthood, they won’t stop a lion from hunting it. That’s just how it is. Maybe hard to explain to an audience who are emotionally invested in the subject and may not have extensive wildlife experience.

(some spoilers ahead)

What was the feeling like when her death was captured on camera?

Beyond heartbreaking but also expected. It wasn’t an unexpected death, when she went into her den after mating and was protecting her eggs, we knew that was the end. Also, she had lived her full octopus life, it wasn’t cut short. It is just how it is. The circle of life as cliched as it may sound. However, this was a beloved octopus, so there was deep sadness and we still get emotional when we watch that scene.

Craig Foster has directed many documentaries and films in the past. When and why did directors Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed come on board?

Pippa came on board around 2016 after the octopus had passed away and we were wondering how to use all of the footage and make a story and we needed someone who had the time and energy and dedication to look through thousands of hours of footage, understand what she was seeing, someone who was as comfortable in the cold water and ocean conditions like Craig and someone with a fine sensibility for telling stories and Pippa had all of that and Craig decided to mentor her.

He was a little too close to the subject, as was I, and we needed an independent eye and Pippa could also edit. When we realised after a few cuts that it would be important for Craig to be in the story himself, Ellen Windemuth, another close friend of Craig’s and executive producer on The Great Dance and on this film, contacted James Reed to get him involved. Pippa Ellen and I were too close to Craig to be able to do the kind of interviewing it would take to get Craig’s story and James came on board to do that.

What was your role as the Production Manager and Associate Producer?

Those were the credits given but being Craig’s partner, I was involved in the process right from the beginning and was part of ideating the whole thing into the story with Craig, Ellen and Pippa. Then being a third eye for the editing process, all the remaining structuring that happened, and just being a support for Craig and Pips, as these were eighteen-hour days in a small room in my house.

Besides the octopus, which other major species has the team at Sea Change Project tracked in the ecosystem? What are the efforts in place to place the Great African Seaforest a global icon?

Craig has discovered & introduced several new species to science. In fact, there is a shrimp here found in the octopus’s den that is named after him, Heteromysis Fosterii . He also discovered and filmed many behaviours of animals new to science. The Sea Change Project dives, films and explores in the Great African Seaforest every day and we keep records of everything we see, and we help to use the science as the foundation for our storytelling. We want to make the Great African Seaforest a global icon and the film has really helped with that. We also do talks; and hopefully after the pandemic, will be taking the film to various communities around South Africa for screenings (Netflix is also getting it translated into several South African languages to help with this). We want to increase awareness, inform science, make South Africans proud of their marine heritage and work towards the long-term conservation of the Great African Seaforest.

Recommended

What are future projects for the both of you?

Craig and our co-founder Ross Frylink are busy with a book UNDERWATER WILD, for international release. We are busy doing our daily work. We all keep records and write stories and keep a track of our footage so if another story seems to emerge organically maybe we will work on another film. There are more books, photography exhibitions and outreach programmes planned.

My Octopus Teacher is currently streaming on Netflix. Members of the Sea Change Project can be reached through their website seachangeproject.com.